Photography is dying—or so many theorists have long declared. We are losing authenticity, control, and meaning, and we are drowning in a deluge of AI-generated images. Yet Joanna Zylinska offers a different perspective. Rather than mourn photography, she highlights its nonhuman elements and claims that photography has always been nonhuman. By doing so, she sees life in photography, while remaining acutely critical of technology, of photography itself, and of the broader conditions that shape human existence.

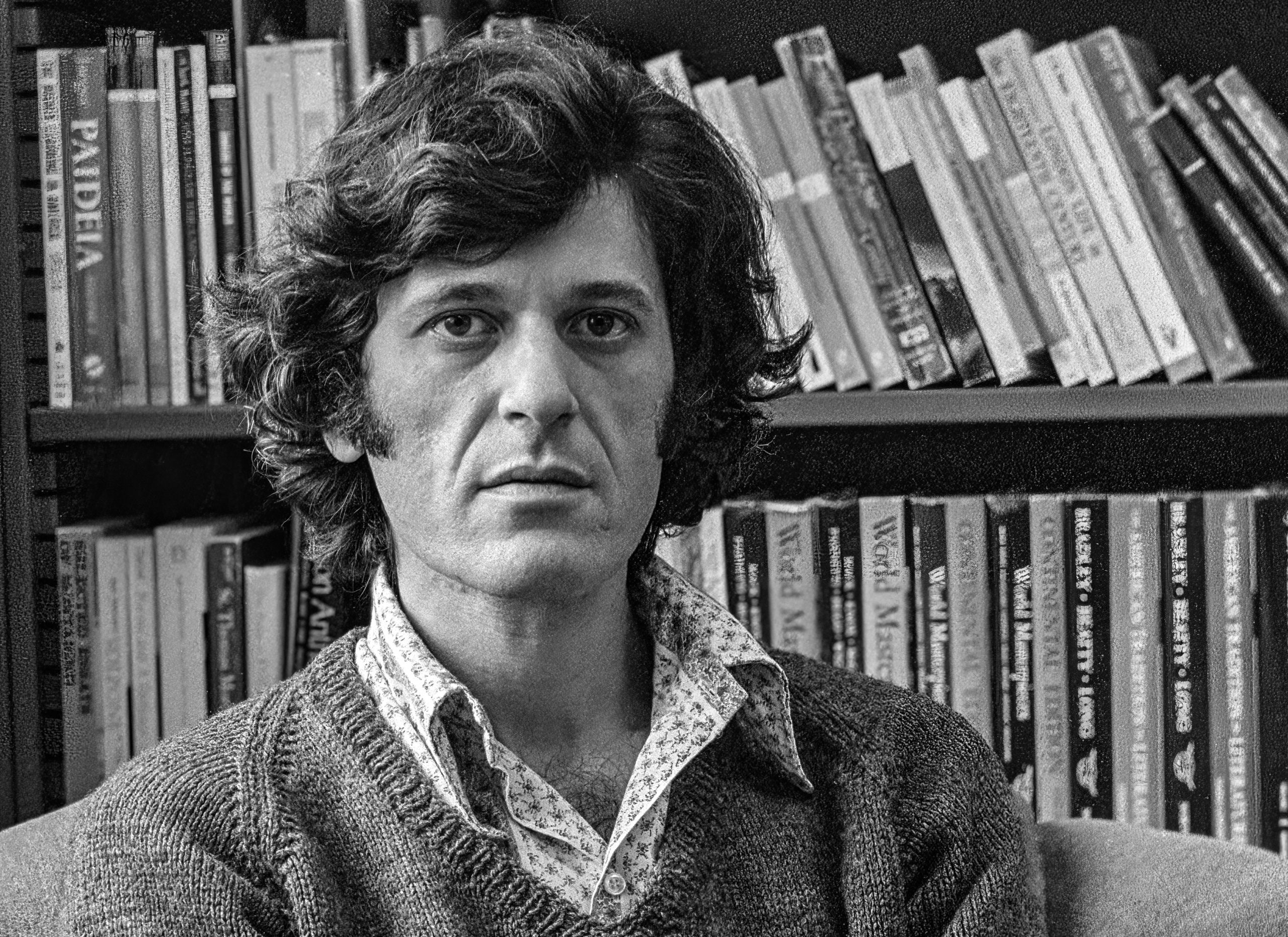

For Zylinska, photography has always been important both intellectually and creatively. A media philosopher trained in fine art photography, she is Professor of Media Philosophy and Critical Digital Practice in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London. She has published nine books, including The Perception Machine (2023) and AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams (2020). Her influential Nonhuman Photography (2017) became the starting point for this conversation. At the beginning of April, I spoke with Zylinska on the Prague–London route—fittingly, over a video call.

TOMÁŠ PACOVSKY: The theme of this issue is “Beyond Media.” In Nonhuman Photography, you “extend” the definition of photography which has always emphasized the representational and humanistic qualities of photography. Why did you decide to “simply extend” it?

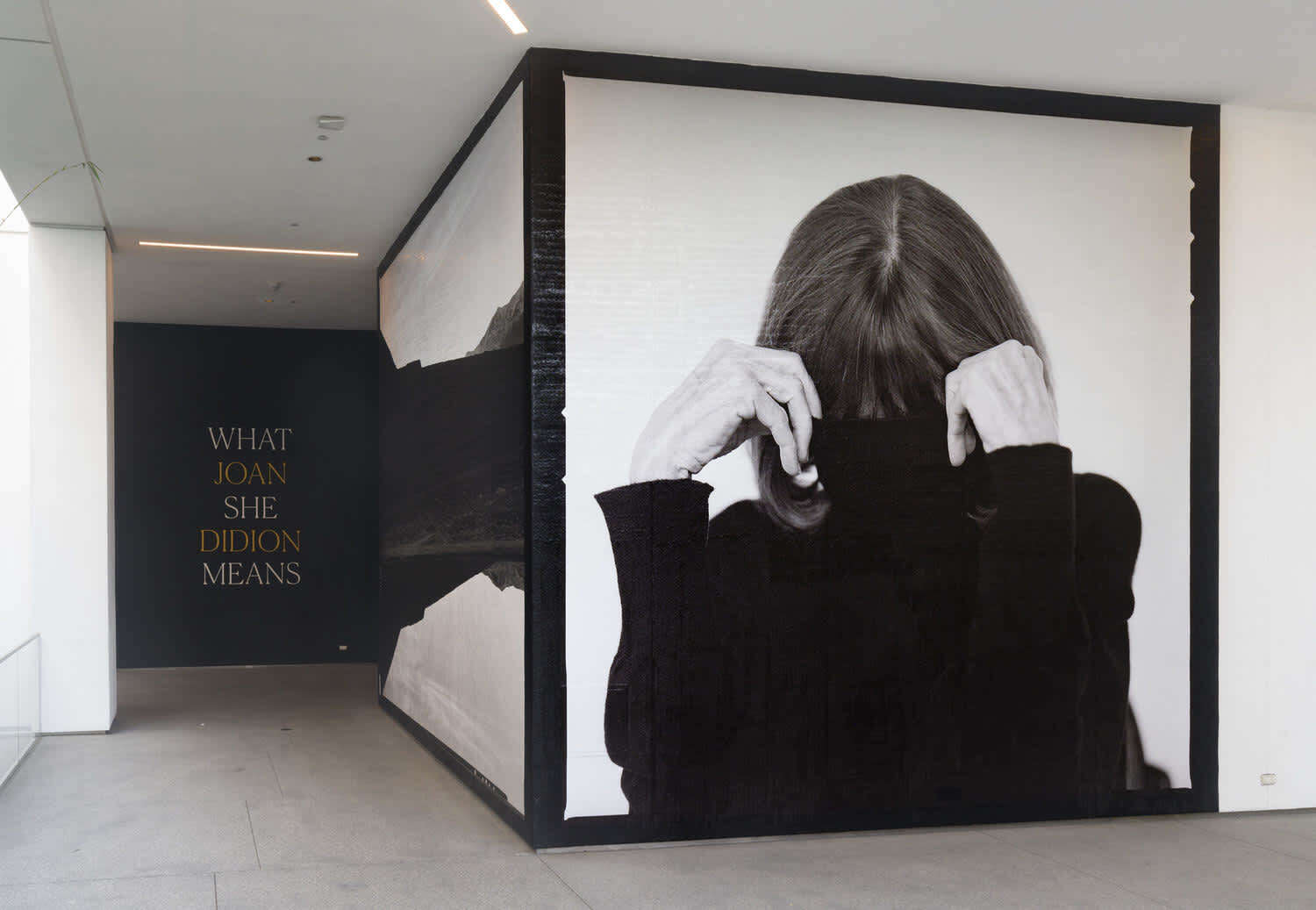

JOANNA ZYLINSKA: Photography is a technology of modernity. It is not just a technology of representation but a medium that involves the stilling of time. As we know from thinkers such as John Berger and Ariella Azoulay, photography is also a technology of colonization and imperialism. And even though the traditional discourse of photography, developed by people like André Bazin and Roland Barthes, has been associated with memory, the passage of time and, ultimately, death, there is an alternative possibility to read photography as a practice of life. As Susan Sontag says: “To live is to be photographed.” The Z generation, with their mobile phones and social media, are living proof of that.

Even though photography today is being radically transformed through both digital and AI practices—to the point where its original definition as “writing with light” is perhaps superseded—photography as a form of cultural memory and technique is still timely. Photography hasn’t gone anywhere, it’s just been reconfigured. But it’s also a medium that’s reconfiguring us.

Nonhuman photography refers to photography not made of humans, by humans and/or for humans. In your texts, you claim that photography has always been nonhuman. What is the closest we can get to a human photograph?

It’s important to emphasize that, for me, the nonhuman is not the opposite of the human. Instead, the nonhuman element is already contained within the idea of the human. This way of thinking is part of an intellectual tradition called “critical posthumanism,” which doesn’t involve an overcoming of the human towards some other species—an android, a cyborg, or AI. Rather, it recognizes that the very concept of the human in Western history has been quite violent—it’s been premised upon the exclusion of many people, social groups, genders, and races from the very idea of the human.

So to introduce the nonhuman as a part of the human is to offer a different way of thinking about ourselves. It’s a way of bringing back a certain humility. This humility is very much needed today, when we are facing multiple crises—from the threat of World War III and nuclear annihilation to the climate crisis.

Photography was invented in the 1820s. Some argue that photography as an idea predates its technical invention, for example, through poetic or painterly practices. Would that be “more” human?

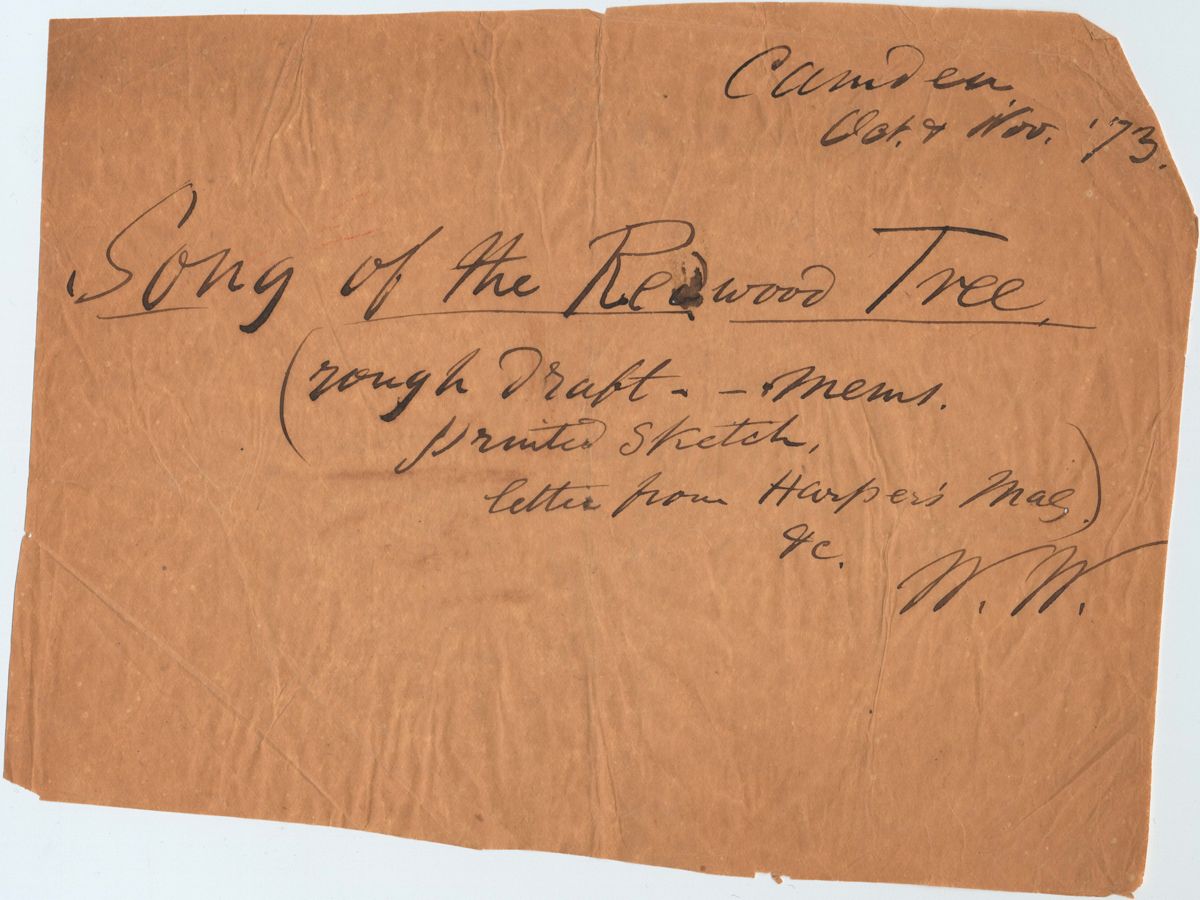

In the book, I do reckon with the traditional history of photography. There are a number of so-called fathers of photography—from Daguerre to Fox Talbot and Niépce. But there is something deeper about photography, also in a temporal sense, which connects it with geology. In the book, I am offering what you could call a geological history of photography. In other words, I am trying to read photography across scales that exceed the human. For example, you could read the practice of making imprints in fossils as a form of proto-photography. The same applies to tanning, or to wax being melted by the sun. Such a practice of image making is automatic, but it’s not necessarily mechanical or technical.

Your book joins the debate about whether or not we should continue using the term “photography.” Other terms include “post-digital photography” or “post-photography.” Aren’t all these strategies just a way to keep a dying medium alive?

Things have changed quite a lot on the photographic front. It’s harder for professional photographers to retain their jobs these days, partly because so-called amateurs can execute high-quality images with their smartphones. Everyone has become a photographer. What counts as evidence today as well as the temporal demands of the media cycle have changed. So there are bigger social and labor issues to be considered.

On the other hand, when people capture images with their mobile phones, they are still calling this act “taking photos.” Photographs taken with a mobile phone still involve light capture. But there are also algorithmic processes present at the very core, to an extent that it’s impossible to take an unprocessed photograph today. Also, you never take a single photograph, your phone always captures a sequence of images. It starts photographing as soon as you show it your desire to photograph something. A sequence of images is being taken and then one is created, with all this occurring outside of your own volition. There is both human agency involved and a suspension of that agency in the photographic process. It’s been like this with photography from the very beginning. A machine, be it a simple one like a camera obscura or a complicated one like a digital camera, takes over from the human at some point, opens the shutter and does its thing.

The reason to propose terms like “nonhuman photography” is to recognize that we are still living in a world where our relationship to photography is important. And even though we’re talking about deepfakes and generative AI, we haven’t overcome the belief that photography can serve as evidence. We still use passports with our ID photos in them. We still comment on our friends’ pictures on Instagram. We know that some of these might have been manipulated. But there is a certain degree of trust. We’re living in a world in which young people are very aware of photography manipulations, and yet they came up with a slogan: “Pics or it didn’t happen.”

When has the essence of nonhuman photography manifested itself for you recently?

I would be careful to use the term “essence”; it’s more like an enactment. It manifested itself, for example, when I was in a self-driving car in China. In a self-driving car, the configuration of imaging, modeling, and sensing is being put together to create an image that won’t be read by the human but by the vehicle.

Interestingly, to reassure the passenger, the human is presented with a model of what the machine sees. Images of the street are captured and rendered in 3D on the map for the human to see, to reassure us, I suppose, that the machine can see everything properly.

There’s also the technology of facial recognition. I have just been asked to submit my passport to one British university in order to receive payment, but the process has been outsourced to an automated, privately-owned platform. What troubles me about some of these gestures is not the nonhuman aspect of photography, but rather the inhumane process of decision making that occurs when you can’t even contest the decisions being made. In this particular case, it’s kind of inconsequential whether I am recognized correctly or not. But a bigger issue arises here when certain inhumane technologies get extended to constant surveillance and monitoring. There is no right of appeal either. And it’s usually the most vulnerable groups in society who are reduced to a 2D image, and who can then be denied access.

Very recently, I realized that instead of simply watching the road to see if my bus is coming, I rely on a live-tracking app—and then I almost miss the bus arriving. Do you see this as illustrative of the way nonhuman photography and other media are reshaping our perceptual habits?

It’s a very interesting example and I think we’re all experiencing some of this. With a research group at my university, King’s College London, we are looking at extended reality (XR). With XR, our vision of reality that comes through human eyes is overlaid with images coming from machines. Also, with AI, you’ve got these multiple layers of reality where you can still see the world as we humans recognize and identify it, and yet there are other processes of translation involved.

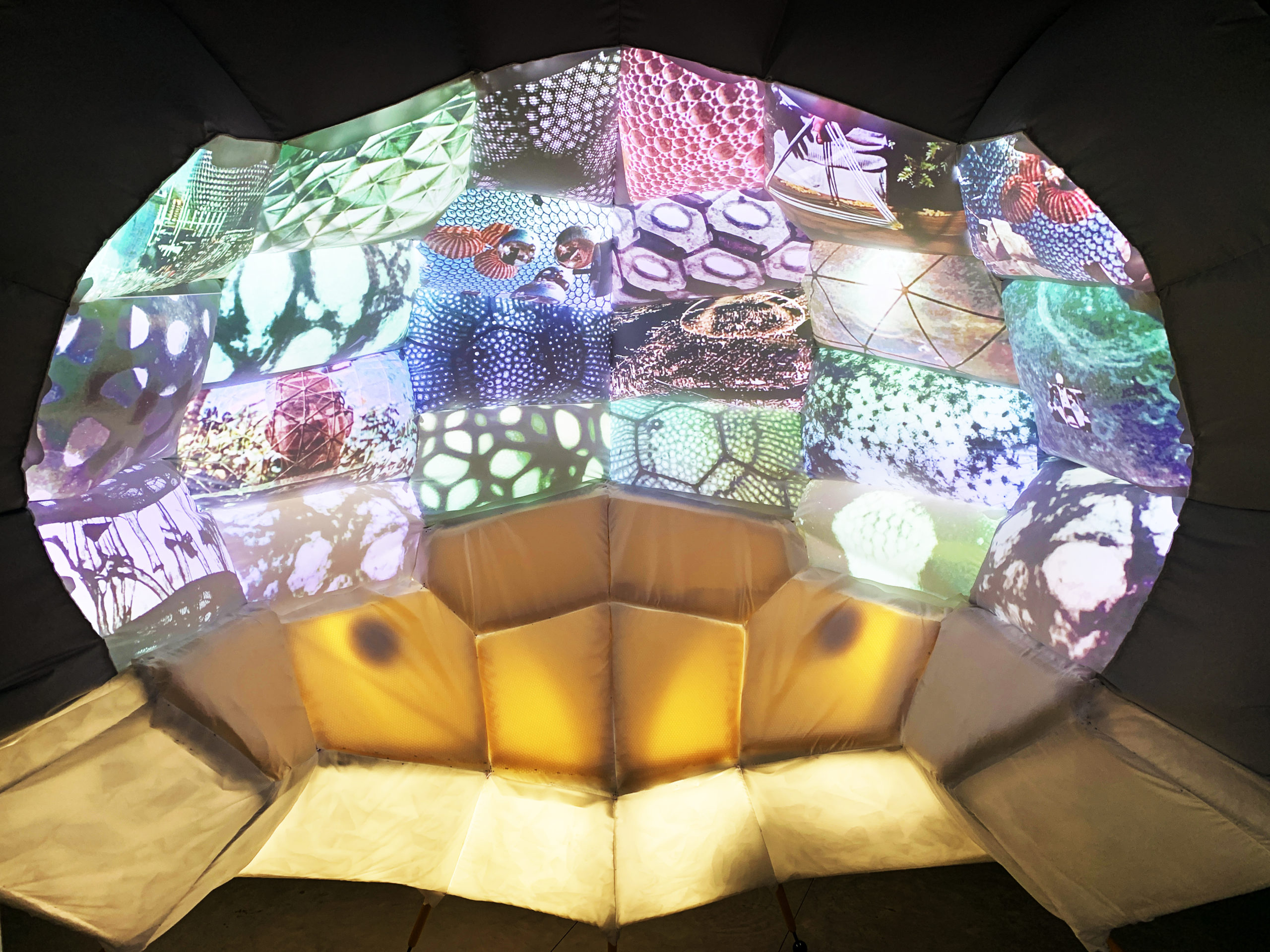

There are many exciting art projects that explore this state of affairs: Mat Collishaw’s work Thresholds (2017), for example. Also, French media company Gedeon creates exciting experiments with VR and XR—most recently a restaging of the first Impressionist exhibition, Tonight with the Impressionists, Paris 1874.

I don’t want to return to the Kantian fantasy of the noumenon, a desire for the thing-in-itself, rejecting all forms of mediation, because, for me, there is no unmediated access to reality. I suppose I am being quite McLuhanian here. We are mediating and being mediated in the relationship with what’s around us through the media and technologies of a given era. These don’t have to be VR sets or mobile phones. They could be simpler technologies, including the actual technology of looking. People need to learn to look in a perspectival way, but that’s not necessarily a natural way of looking. Maybe there isn’t a natural way of looking at all. Even something as seemingly biological as perception is already a product of a particular training of the eye-brain-world configuration, as Jonathan Crary illustrates in Techniques of the Observer (1990). Even direct perception is mediated.

In your image series, Active Perceptual Systems, you ask whether the human should continue being the creator, or rather take on the role of an editor. What is the answer?

The project is responding to the idea that every image has already been taken by somebody else. Can you take an original picture of the Eiffel Tower? Or are these images—as we see in multiple Instagram reels where people repeat the same tourist gestures—just a quotation of something else, previously captured? As Umberto Eco asked: Is it possible to tell someone “I love you” without this very personal statement being a citation from literature, cinema, or other cultural scripts? But even if you recognize that and continue saying “I love you,” it doesn’t mean you’re not being authentic.

This citational authenticity, if you like, becomes a form of editing. Indeed, our use of language overall is a form of editing. Accepting that sense of being an editor is an attempt to remove the stigma that reduces the editor to just an uncreative arranger of things. Maybe being an editor is the only function available to us. But if that’s the case, how do we do it well? Not just in terms of performativity, efficiency, or—to use that favorite word of the tech bros—productivity, but also in terms of that ethical relationship with others. Who would a good editor of images be? For me a good editor of images is a good editor of meanings.

Has the rise of AI changed your thinking about nonhuman photography?

Vast swathes of photographs have been taken from the web and used to train AI. This infrastructure of generative AI, which you could call post-photographic, is still very much reliant on photography. But photography becomes hidden, obscured, in those datasets. It’s there, lingering, but as a shadow, a ghost. So by retaining the term “photography” I am trying to bring it to light. I also recognize that many of the images in those datasets were taken by machines. Some of them might have even been artificially generated, which is why they all inscribe themselves in what I term “nonhuman photography.”

An interesting thing for me is the possibility of a nonhuman language developing from within these image generation processes that we humans don’t really have access to because of blackboxing. Some of the AI models might eventually bypass our human processes of perception, cognition, and understanding; they may develop a different form of communication that makes sense to them.

Since AI models are trained on images produced by humans, and potentially on our stereotypes, doesn’t this nonhuman technology reveal a lot about us humans?

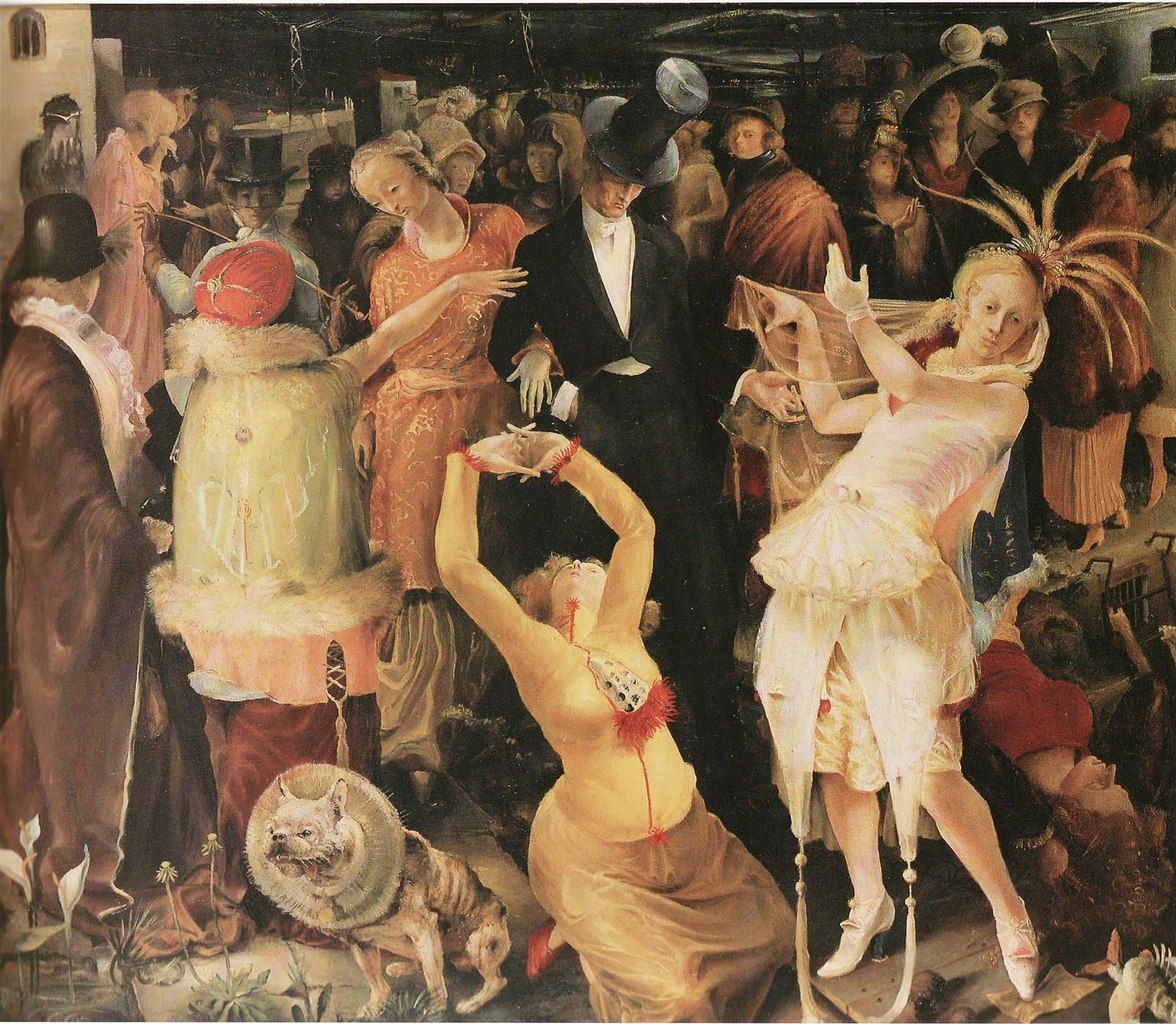

Absolutely. AI is holding up a mirror to us. And again, some of these moments of reflection are also opportunities to bring a certain humility to the idea of the human. Of course, you can say that they reveal the training engineers’ or annotators’ biases but I think there is something else there. The databases are collections of our cultural imaginaries. They are therefore interesting because of what they reveal and what they conceal. There are multiple groups that are responsible for the construction of those databases and models but, in some sense, those data sets reveal something about us. I don’t think this something is completely transparent. Again, some critical labor is required to see what we are seeing—and what is being seen by machines.

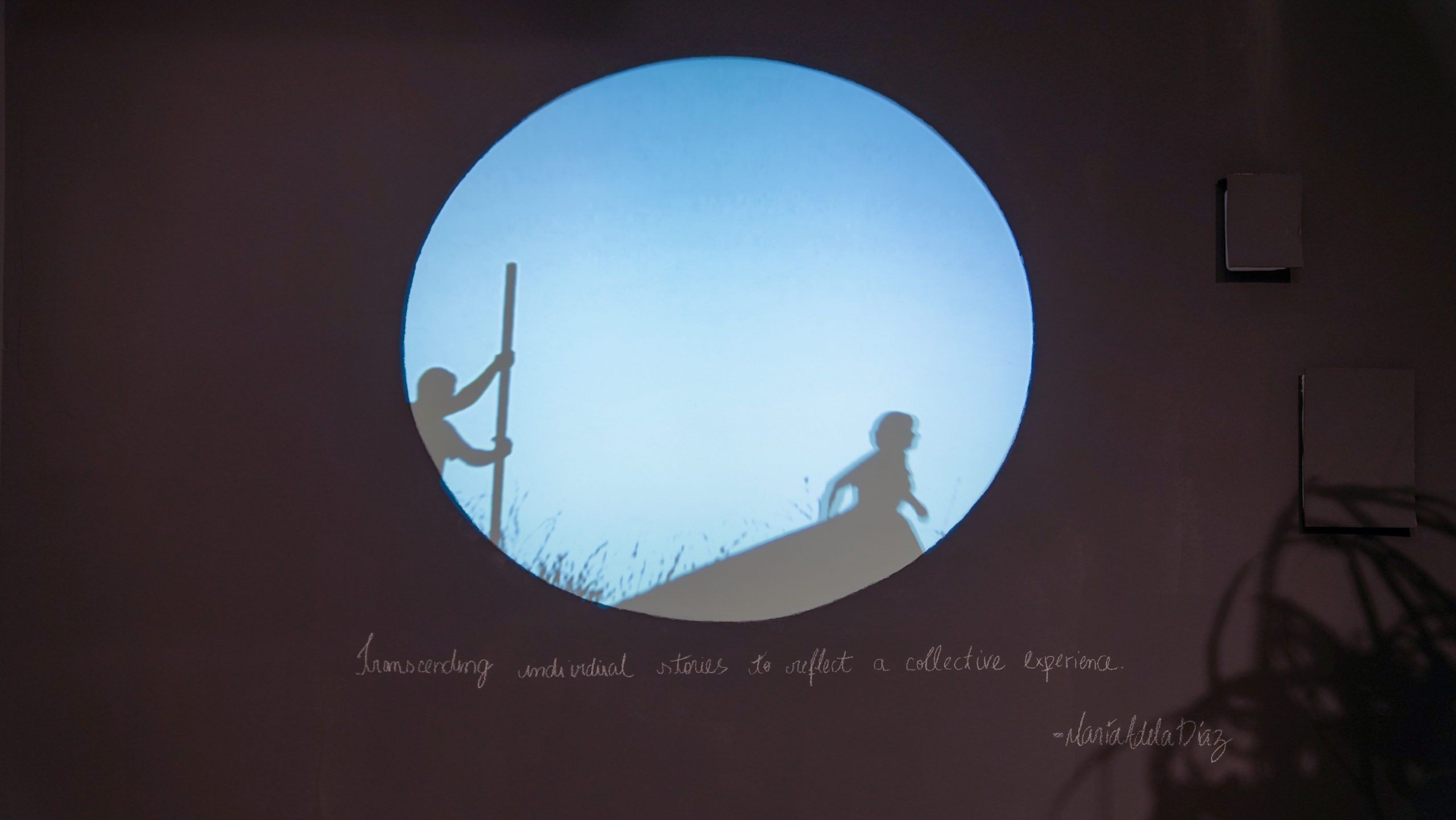

You work as both a theorist and an artist. How does your artistic practice inform your writing and vice versa?

I try to develop them in parallel. But I also recognize that different media have their own specific affordances. I don’t use creative practice as an illustration of my philosophy but as a way of developing ideas—and sensations—in a different mode. In a way, it’s surprising to me that more academics are not doing this. I try to introduce this multi-modal way of working in my teaching too. I get my students at King’s to do video essays. Some of them get nervous as they don’t see themselves as very visual. They know what it means to write a standard essay for school. And then, they end up doing their video essays which end up being much better than their conventional essays because students today have so much visual literacy. They just need reassurance that what they consider as a fun part of their lives is also a valid mode of knowledge production.

With nonhuman photography you have challenged a core assumption about photography. If you could challenge another fundamental concept in media studies today, what would it be?

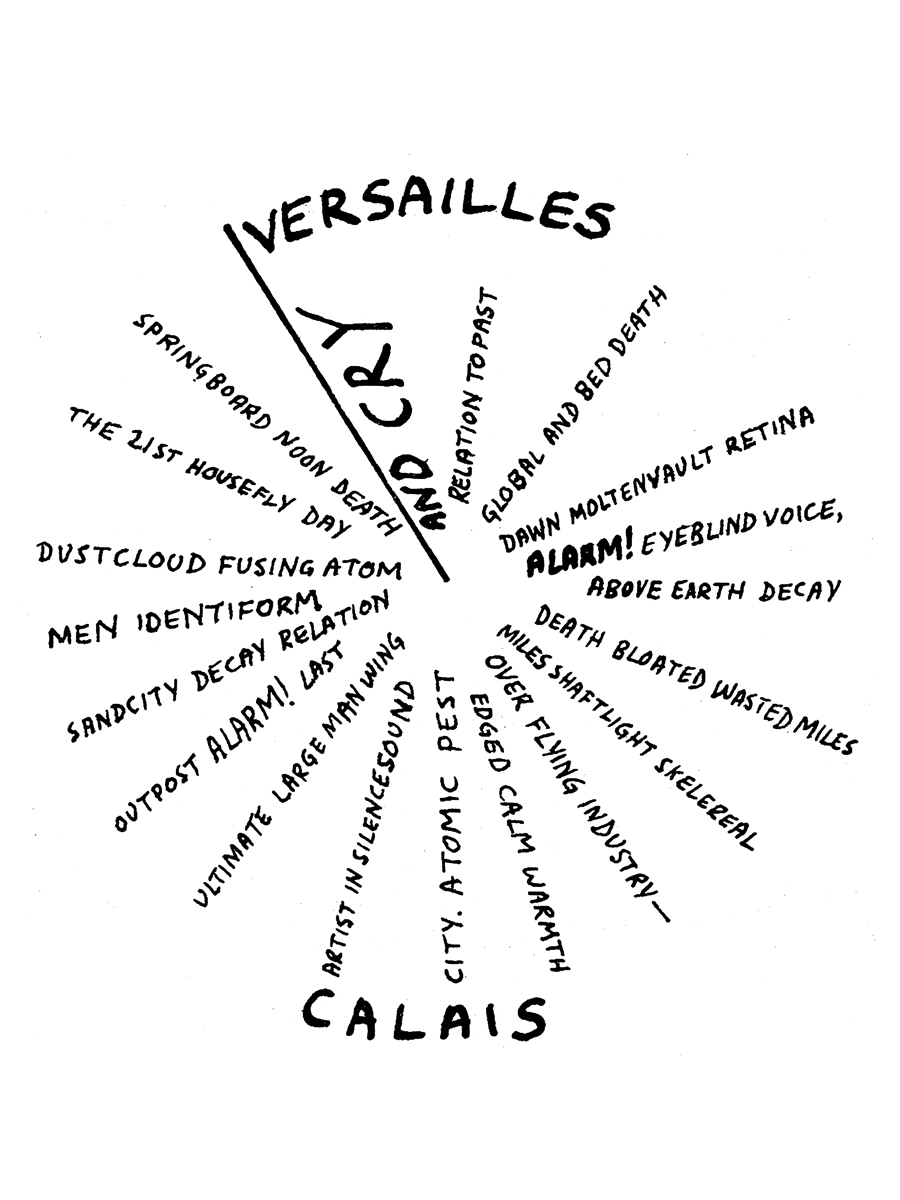

I would like to return to a more creative, seductive way of writing. What troubles me is that more and more articles, which increasingly get described as “papers,” have a publication model which is very much based on the sciences. They have to have an introduction, a literature review, a certain set of quotations and references. The seduction aspect of writing is very visible in French theory—from Baudrillard to Deleuze, Virilio and Cixous. That kind of writing is more explicitly ambiguous and poetic. So I would bring back the sense of openness and lightness to language, as a way of recognizing language as a medium and not just as a transparent device that can get us from A to Z.