[drop-cap]

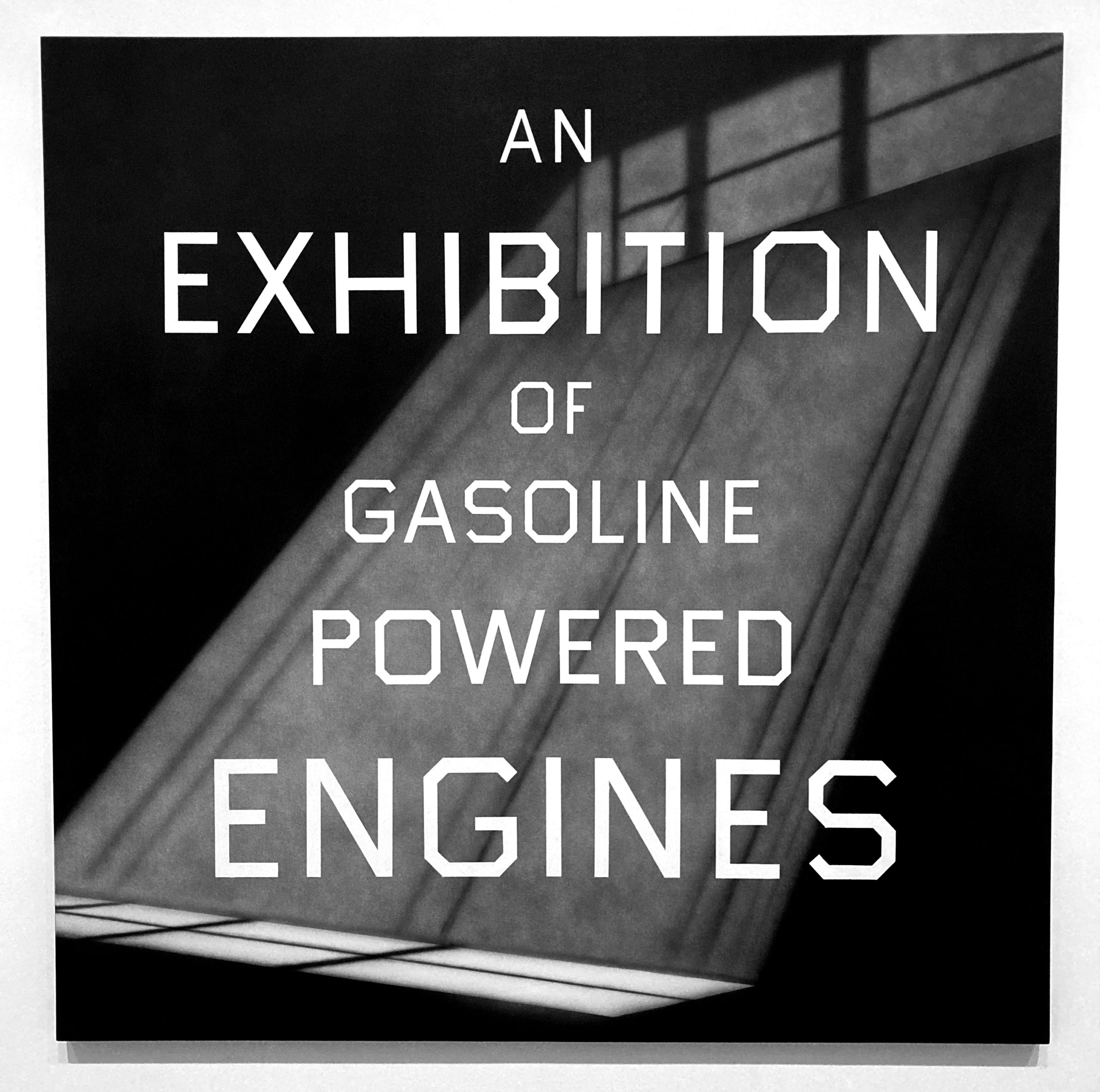

It doesn’t get more underground than this: inside the Fifty-Third Street E/M Station in Midtown Manhattan, nestled between the Museum of Modern Art and UNIQLO, Emmelines is a gallery for contemporary art projects founded by William Wiebe. Occupying a former newsstand (behind the entrance door, a ghostly sign still reads: The New York Times On Sale Here), its modest vitrine and tiled surroundings belie the depth of its programming—fittingly described on Instagram as Station Arts & Métiers—which already features an impressive roster of important contemporary artists.

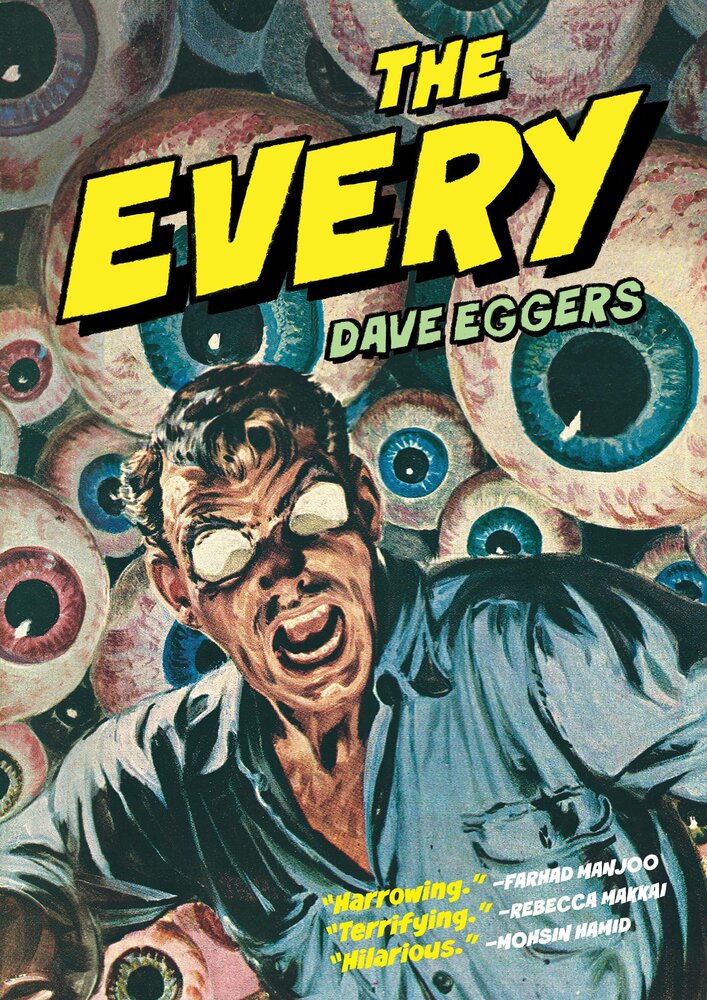

On show from October 20 to December 1, 2025, Pierre Leguillon’s Held marks the French artist’s first solo exhibition in New York. Known for his incisive, often ironic entanglements of art and mass media, Leguillon moves fluidly between the roles of artist, curator, critic, and teacher. For over two decades he has reactivated canonical twentieth century works he considers “paralyzed by history,” re-presenting them through books, slideshows, installations and exhibitions that blur the boundaries of authorship and spectatorship.

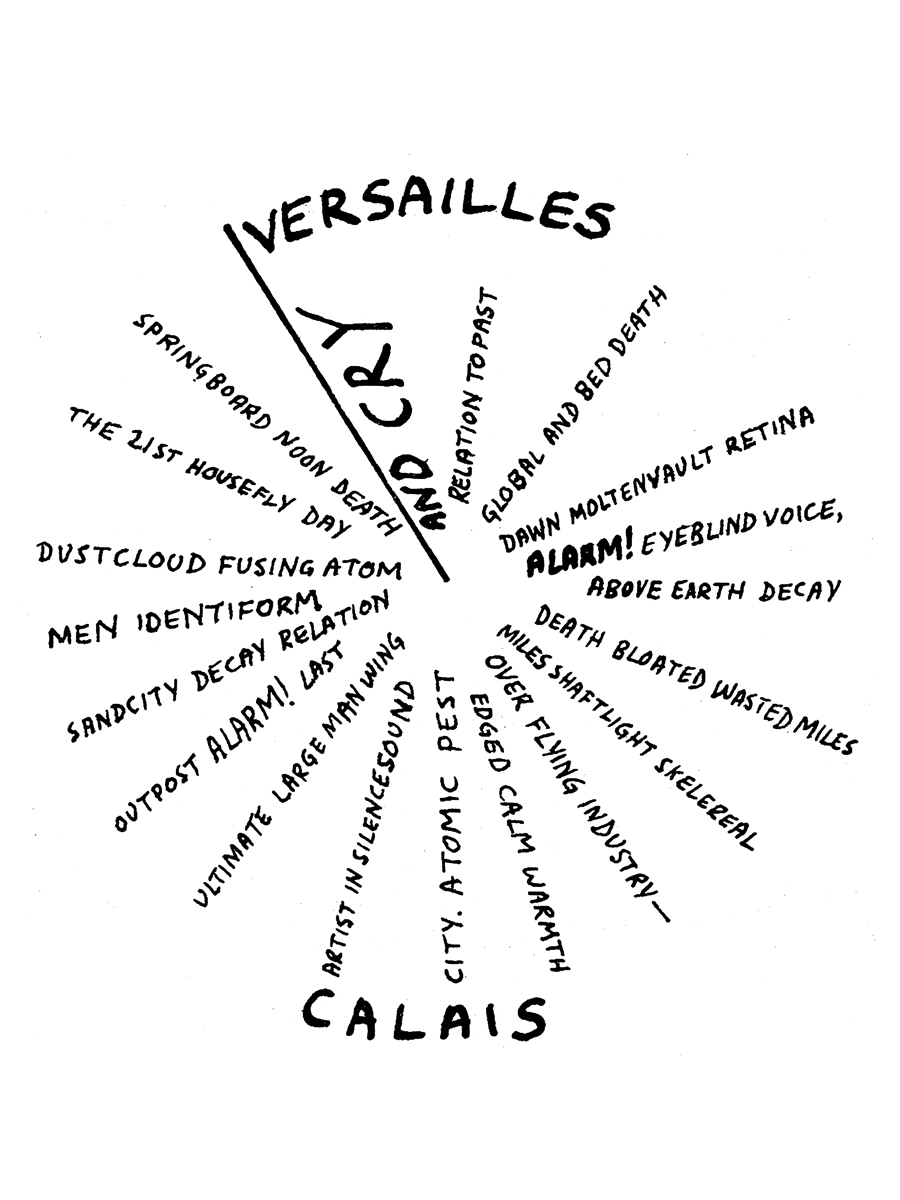

Inside Emmelines, selections from Leguillon’s archive of artists modeling in advertisements are displayed alongside Mérida, a painting inspired by a mural in a Mexican bar, printed on Japanese fabric, and sold by the meter. A table displays several of the artist’s books. Pamphlet—a triptych of mid-century advertising posters reimagined as a single tableau—occupies the center of the space, visible through a glass wall to subway commuters. In French, pamphlet suggests political critique, but here it becomes a quiet act of détournement: The three large lithographs form a dramatic display in the gray subway station. Leguillon summons the French flag, yet he evokes it ironically as a flag of commerce rather than of nationhood.

Each of the three posters—Swiss and Bavarian originals—commemorates a fragment of postwar Europe. On the left, Münz-Brauerei Günzburg’s Humbser Alt beer poster entices consumers with a bright blue background and the slogan “Schon probiert…?” (“Tried it yet?”). The word ALT—German for “old”—reads today as both nostalgic and potentially digital, echoing the computer key that modifies or “alters” functions. For some it may also recall Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the right-wing populist and nationalist political party known for its strong anti-immigration stance, Euroscepticism, and criticism of established political elites.

In the middle of the triptych, the Swiss brand Thomy’s – der gute Senf (“the good mustard”), from 1946, turns condiment into pure color field. Its designer, Jules Glaser, rendered postwar optimism in industrial yellow, an American-style gloss at a time of European austerity. “What would a New York show be without a bit of mustard?” the work seems to tease. One can’t help but think of Warhol’s Mustard Race Riot (1963), featuring LIFE magazine images of police brutality in Birmingham, Alabama, juxtaposed against an expanse of mustard yellow. Warhol’s hue burns with moral tension; Leguillon’s mustard is commodity fetish. Both, ultimately, trade in color as power.

Once a site of daily transactions—where one might have bought a newspaper, or even mustard—Emmelines now stages an archeology of aesthetic contemplation.

The final poster, TAT, Kräftig! (“TAT, powerful!”), advertises a 1959 Zurich newspaper. The rolled-up paper asserts its own materiality, the promise of news as an object one could hold. While these hand-painted, pre-Photoshop ads—already signed by their original designers—form a tricolor ensemble resembling the French flag, nothing in the show is French, except perhaps its wit. The language is German; the sensibility, European modernist. The juxtaposition of these ads—beer, mustard, and press—suggests not just the postwar optimism of European reconstruction but also a meditation on soft power, commerce, and cultural identity. In 2025, the flag remains a contested sign: Who may claim it? Who may reframe it? One also recalls Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Forbidden Colors (1988), a four-panel monochrome painting representing the colors of the Palestinian flag.

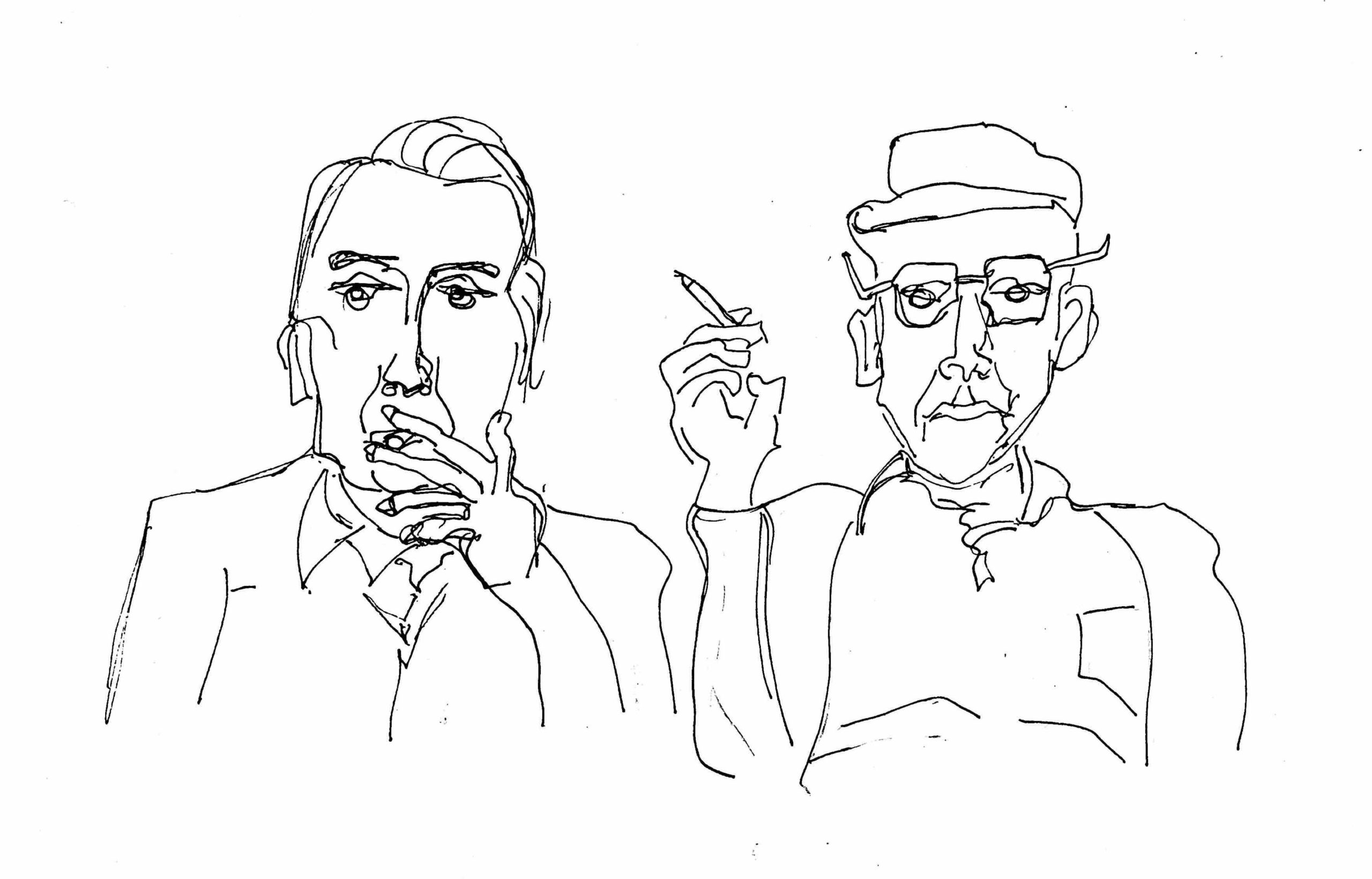

The location amplifies these questions. Once a site of daily transactions—where one might have bought a newspaper, or even mustard—Emmelines now stages an archeology of aesthetic contemplation. In this setting the posters, relics of a bygone commercial age, alongside the framed fabric and magazine pages, function like artworks. Their colors hum with the craft of pre-digital printing; their slogans read as anachronistic poetry. Seen beside Leguillon’s more recently collected images of artists modeling in advertisements—including Marina Abramović for Givenchy, Seth Price for Brioni—one might conclude that little has changed in the visual logic of persuasion and advertisement since Midtown’s Mad Men heyday. Even Abramović, framed through couture, feels like an artifact of a previous century’s belief in the artist as brand.

This choice of matter reflects Leguillon, born in the outskirts of Paris, the city where he spent most of his life tied closely to its cultural institutions. Now based in Brussels and teaching in Switzerland, he personifies the itinerant pan-European artist-intellectual whose identity is both local and transnational—a position that feels increasingly fraught as the European Union faces new fractures like nationalism, war, and cultural retrenchment. The show’s title, Held, captures this double bind. In English, it means both grasped and constrained; in German, it means “hero.” What, then, is being held—national identity, artistic autonomy, or Europe itself?

While Switzerland is the oldest democracy in the world, France has always prided itself as the patron state of the arts; post-Brexit, Paris has further reclaimed its place as the capital of contemporary art. France finds itself in a paradoxical state: politically brittle, culturally decadent, yet newly assertive on the global stage. With private foundations (Cartier, Pinault, LVMH) dominating its contemporary art scene and the Pompidou Center shuttered for renovation, Paris has become both the beacon and the cautionary tale of cultural capital. The tension between national heritage and global capital—between patrimoine and branding—echoes through Leguillon’s subtle détournement of advertising language.

The recent theft of the French Crown Jewels from the Louvre has been compared, in the conservative French media platforms, to the beheading of two teachers by Islamic extremists—a striking conflation of national trauma and cultural loss. Postcolonial commentators counter that the jewels themselves symbolized France’s imperial project, and that the museum’s vast collection of looted artifacts remains largely unrestituted to their countries of origin.

As the Venice Biennale approaches, its persistent hierarchies and national designations again come into view. Many of today’s participants represent countries they no longer inhabit—such as Oriol Vilanova, the Brussels-based artist chosen to represent Spain—suggesting that the national pavilion framework insists on performing something no artist quite believes in. Leguillon’s composite poster flag holds together fragments of national and European identity, as if testing whether they can still signify in a transitory space—a subway newsstand turned gallery—beneath the indifferent gaze of a city that houses an ever-weakening United Nations.

Held: Pierre Leguillon at Emmelines

October 20 - December 1, 2025

5th Ave & 53rd St MTA Station Mezzanine Newsstand

Entry at 10 W 53rd St & 1 E 53rd St

Open Thursday–Saturday, 2:30–6:30pm & By Appointment

info@emmelines.biz & 415 336 4800