[drop-cap]

My first visit to London, and the Tate Modern, occurred during the last of my teenage years, at the end of one period of my youth and the beginning of another. Though I’d travelled with a friend, I visited the museum alone. I don’t remember why. Looking back, it’s entirely within my current character to have spent that time visiting an art museum, but to look at that day without the context of the rest of my life makes the choice much less obvious.

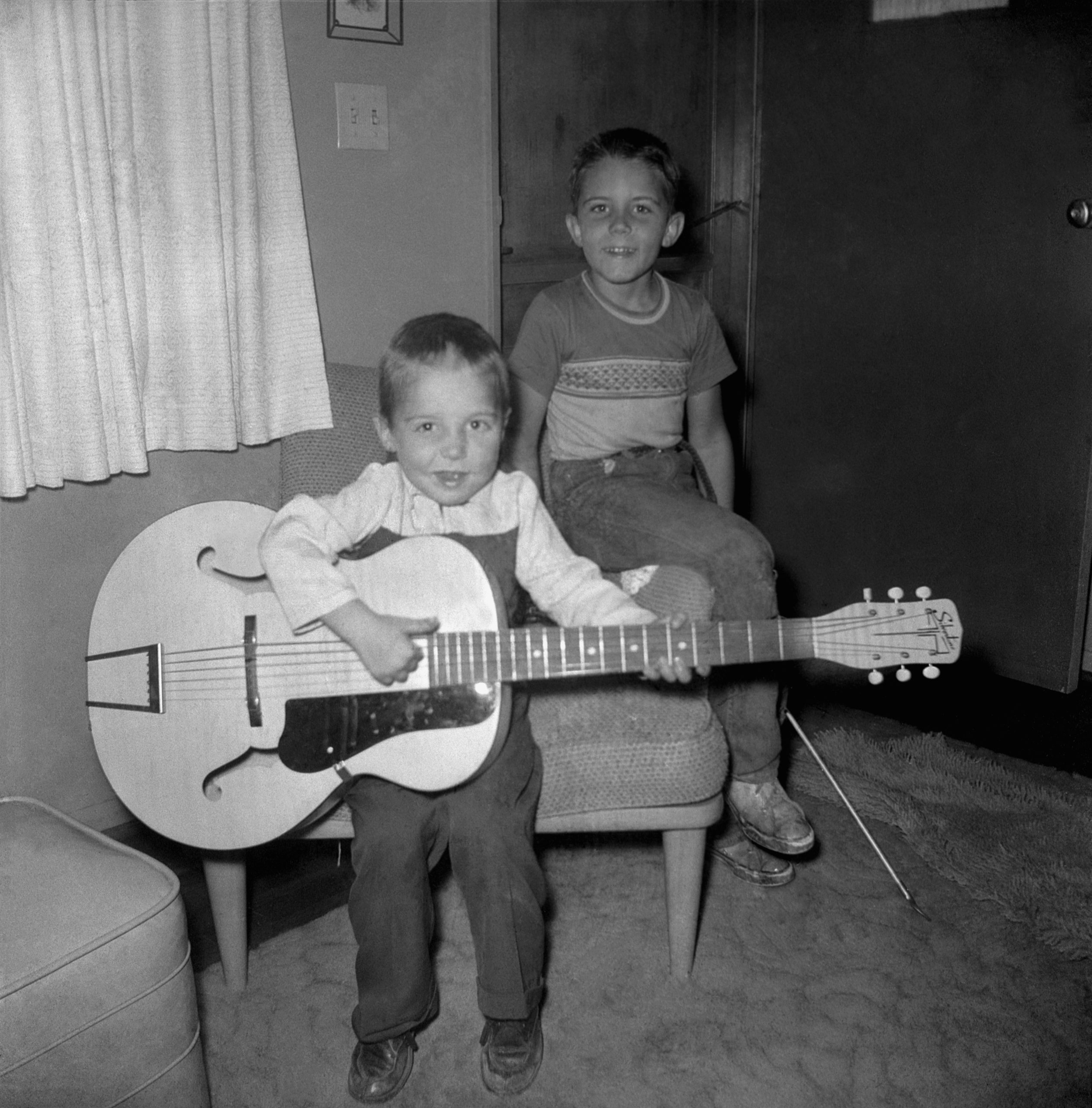

I’d grown up in a small town an hour and half outside of Austin, Texas, where I attended college. There’s a small museum, though I’d likely never gone, not because I wasn’t aware of art—I had plenty of artists whose work I liked—but because it wasn’t something people did. Not like later, in New York, when knowing all of the exhibitions going on in the city was normal, even expected, and visiting multiple within the span of a single weekend meant time well spent. None of that had happened yet. This was 2012. The Internet didn’t exist in the way it does today. Influencers didn’t exist the way they do today. There were no people posting curated, minimalist photos in upstate New York museums, or collaborating with art-minded brands. I’d gotten there some way I’ll likely never recall. Isn’t it funny, to have done something and to have no idea how you ended up doing it?

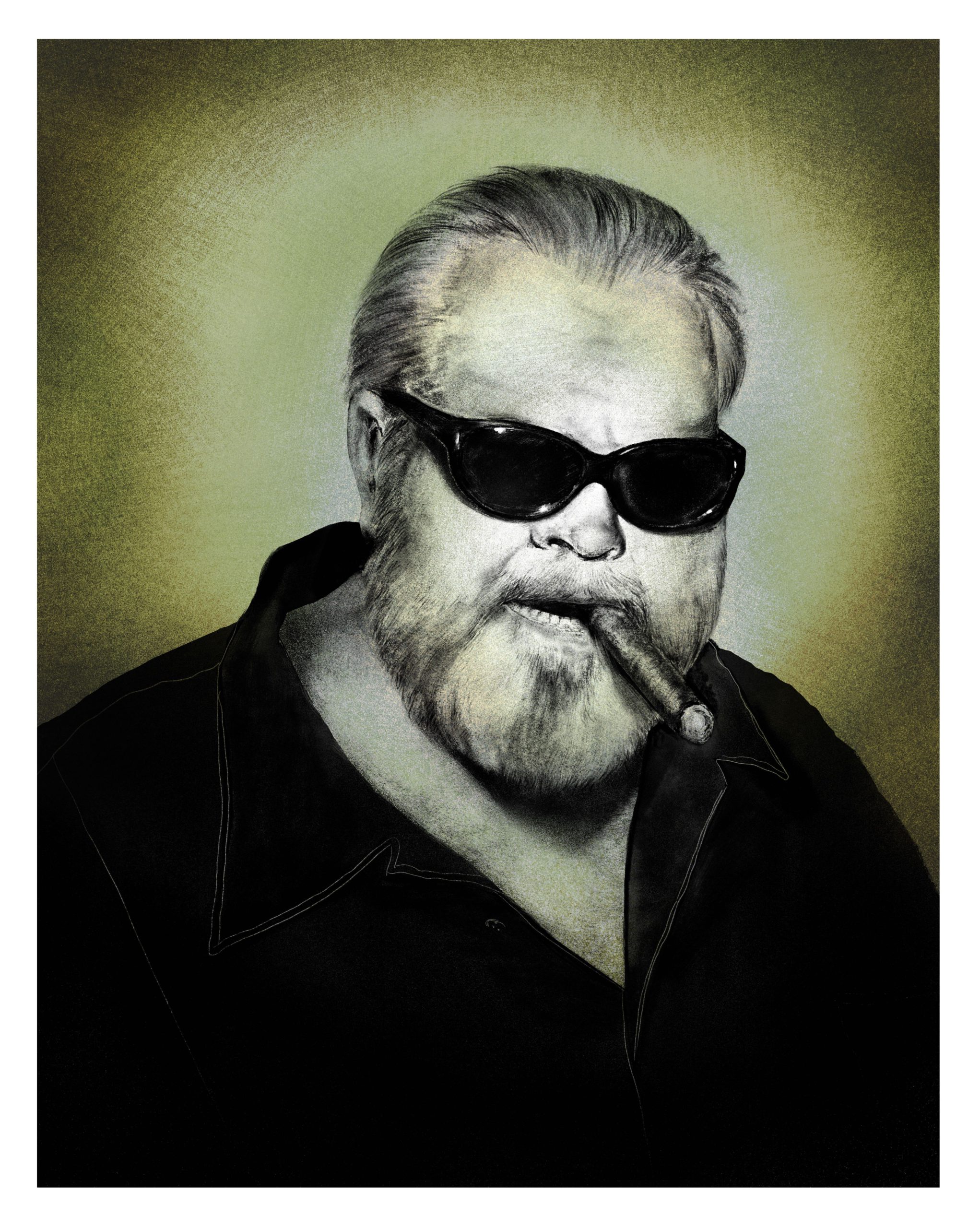

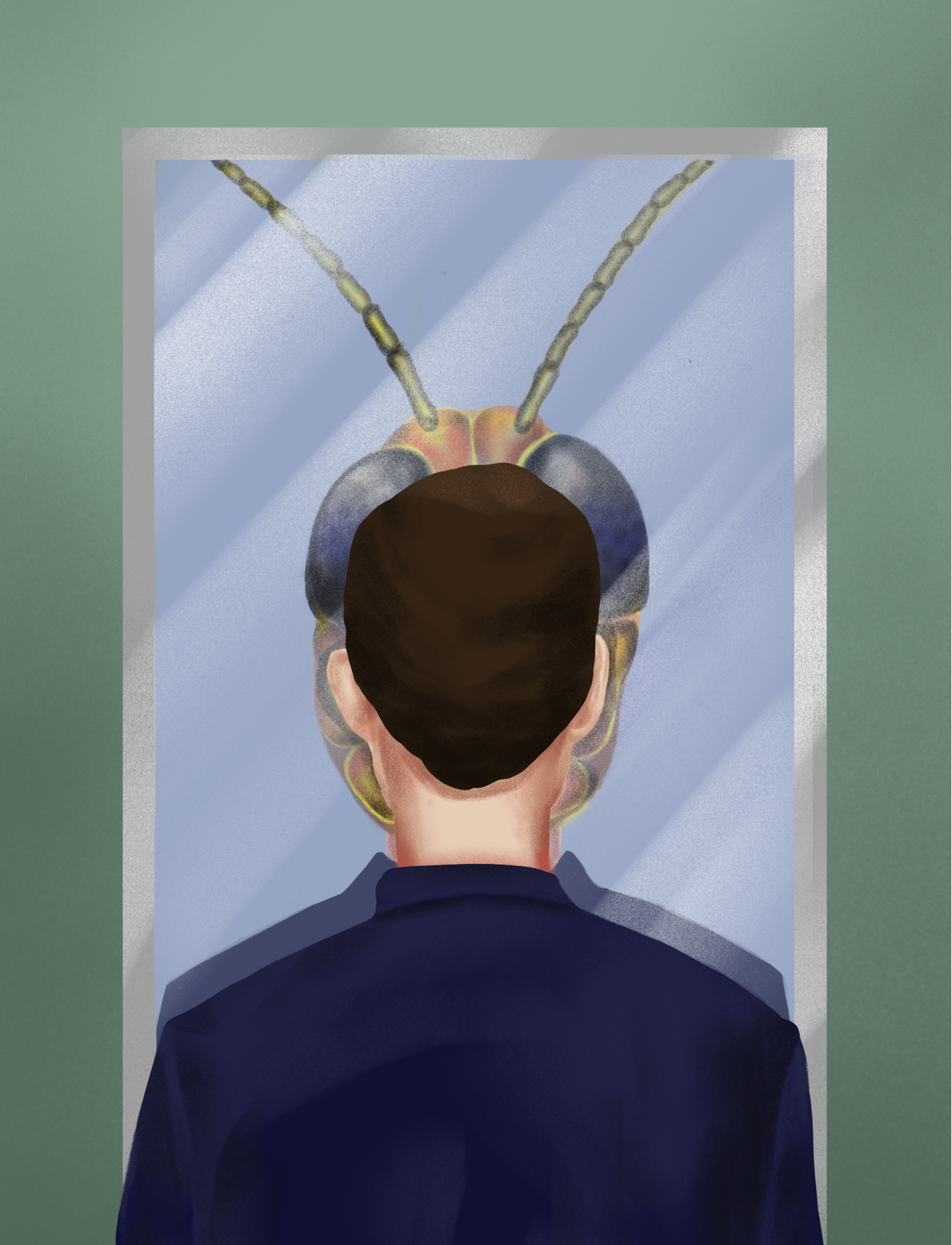

I suppose, at the time, I thought of myself as a person interested in art. Yet I had no vocabulary, no mind for articulating any coherent thought about what I looked at. I remember feeling continually dumbstruck (a feeling that persists even now). During that first visit, there was a Damien Hirst exhibition on and I studied the shark suspended in windex-blue liquid for a long time. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. I studied the rows of prescription pill bottles. Pharmacy. I studied the insect-electrocuting light suspended over a cow head being eaten by maggots that metamorphose into flies which fly into the insect-electrocuting light, then die. A Thousand Years. In a review of the show in the Guardian, art critic Adrian Searle wrote, “One wants to write a straightforward review of Hirst’s work, but it is almost impossible. What would it be like, I wonder, for someone with no knowledge of his art, let alone his global reputation, to come along and review this show? What would they see?”

This past summer, Emily Kam Kngwarray’s retrospective was on at the Tate—the first ever in Europe or the UK—and the exhibition was nothing like Damien Hirst’s. A member of the Anmatyerr people from Alhalker Country in Australia’s Northern Territory, she is, even decades after her death, one of Australia’s most important and celebrated artists, with a practice rooted in Indigenous knowledge passed down through generations. Her work draws on her relationship to Country—the ancestral land of her birth, land that she inhabited all eighty-five years of her life— and The Dreaming, a term for Aboriginal Australian stories about time, creation, and ancestral spirits. Kngwarray’s paintings pull viewers into the ways of life of the Anmatyerr people and thus pull them into a way of being that feels at once foreign, at least to me, and yet undeniably true.

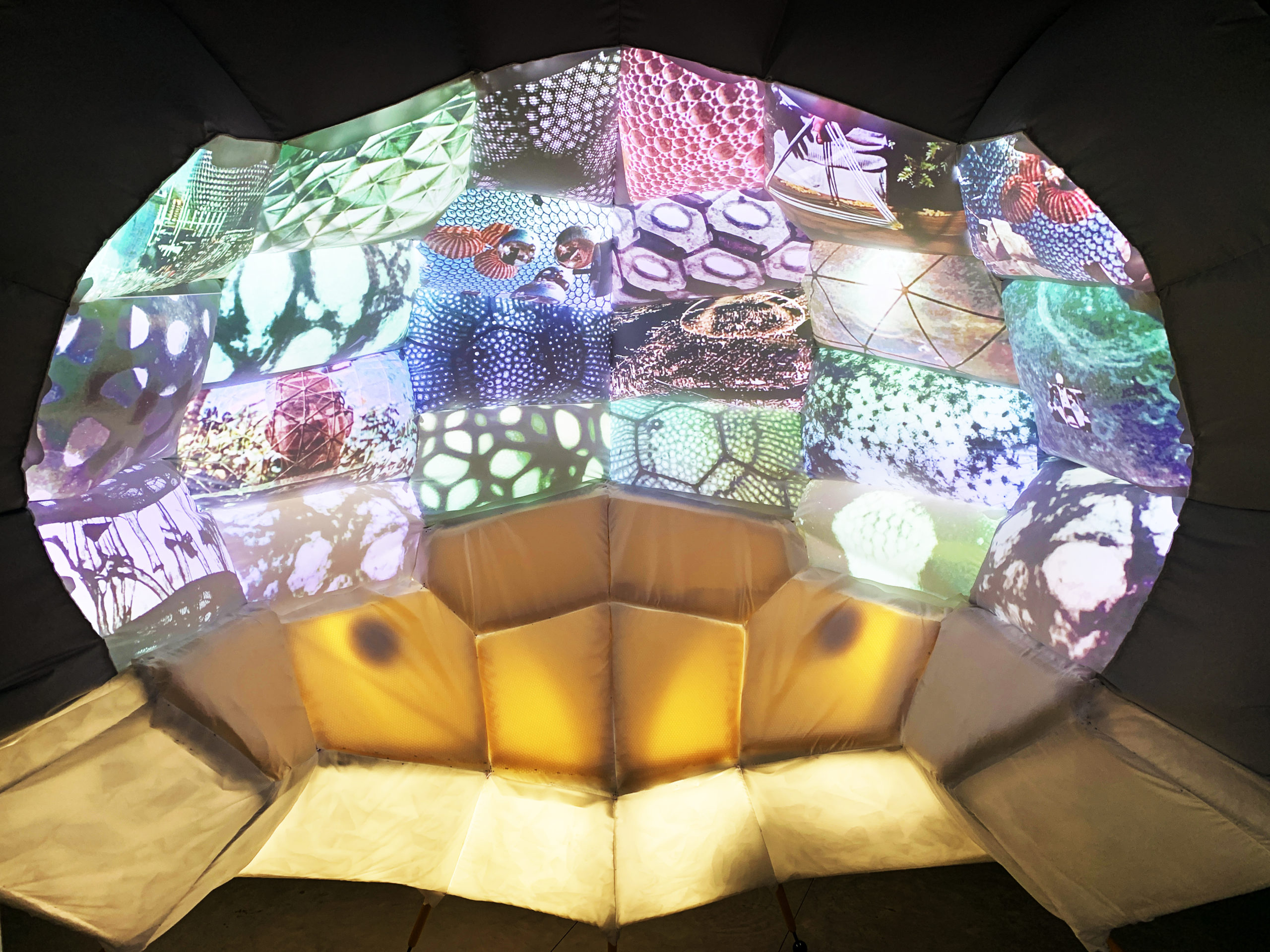

Upon entering the first room, there was chanting, or singing, before any artwork was visible. Right away, I got the sense that something about the show, about Kngwarray’s work, would elude me. Once the paintings came into view, I recognized that within them existed a connection to a place—and all that place represented—that I would never have. But the feeling didn’t deter me. Instead, it released me from looking at art the way I thought a person needed to. It released me from the knowledge I had, and didn’t have, about Western art history. Knowledge is liberating. It is also a burden. After I’d gone through the entire show, I felt sure that letting go of understanding was necessary to engaging with Kngwarray’s work. Some people need to leave home to understand it, while others, like Kngwarray, do not.

Recently, a feeling of discontent had crept into me, the origin mysterious, though I was aware that feeling untethered at the dawn of your thirties was entirely ordinary.... Kngwarray and I had opposite problems. She knew what she looked for. She could imagine her world. I was trying to conjure my own, from nothing.

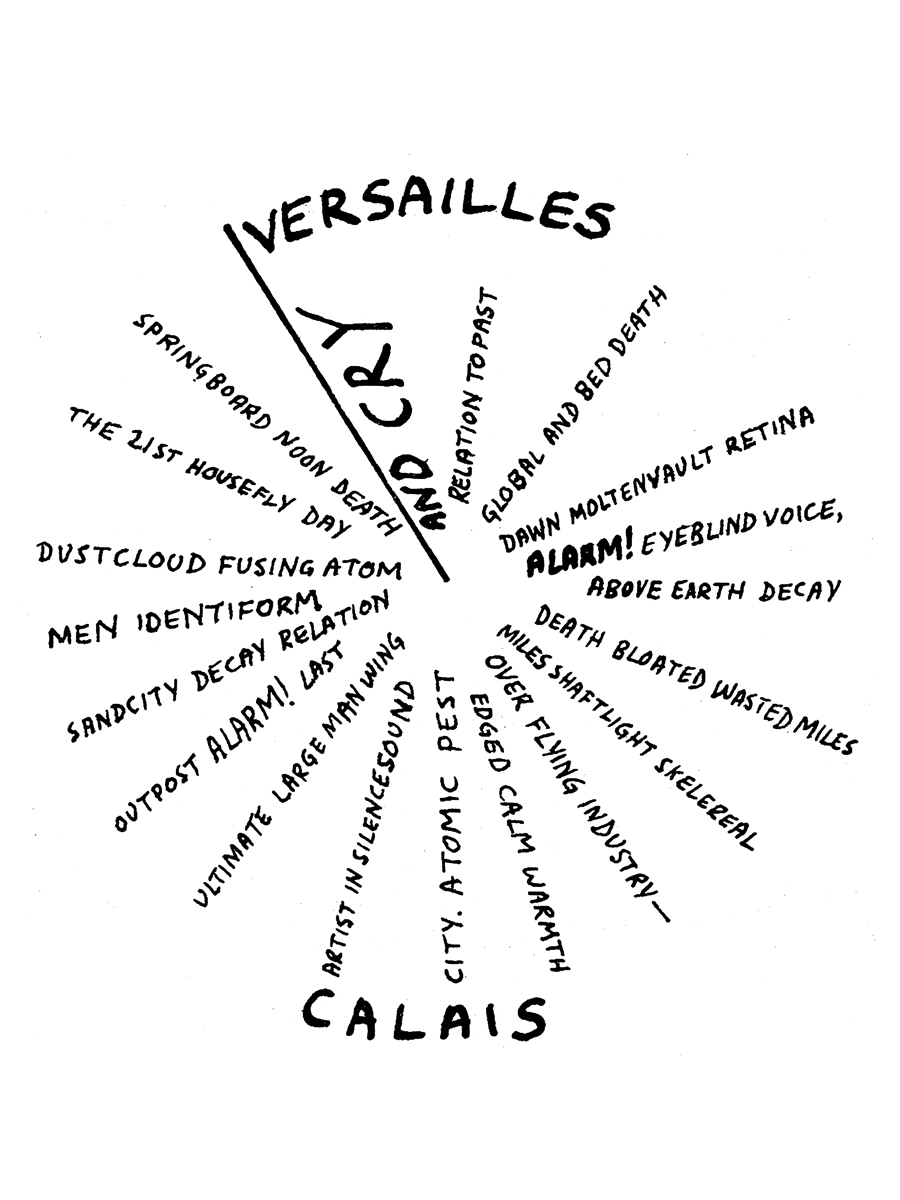

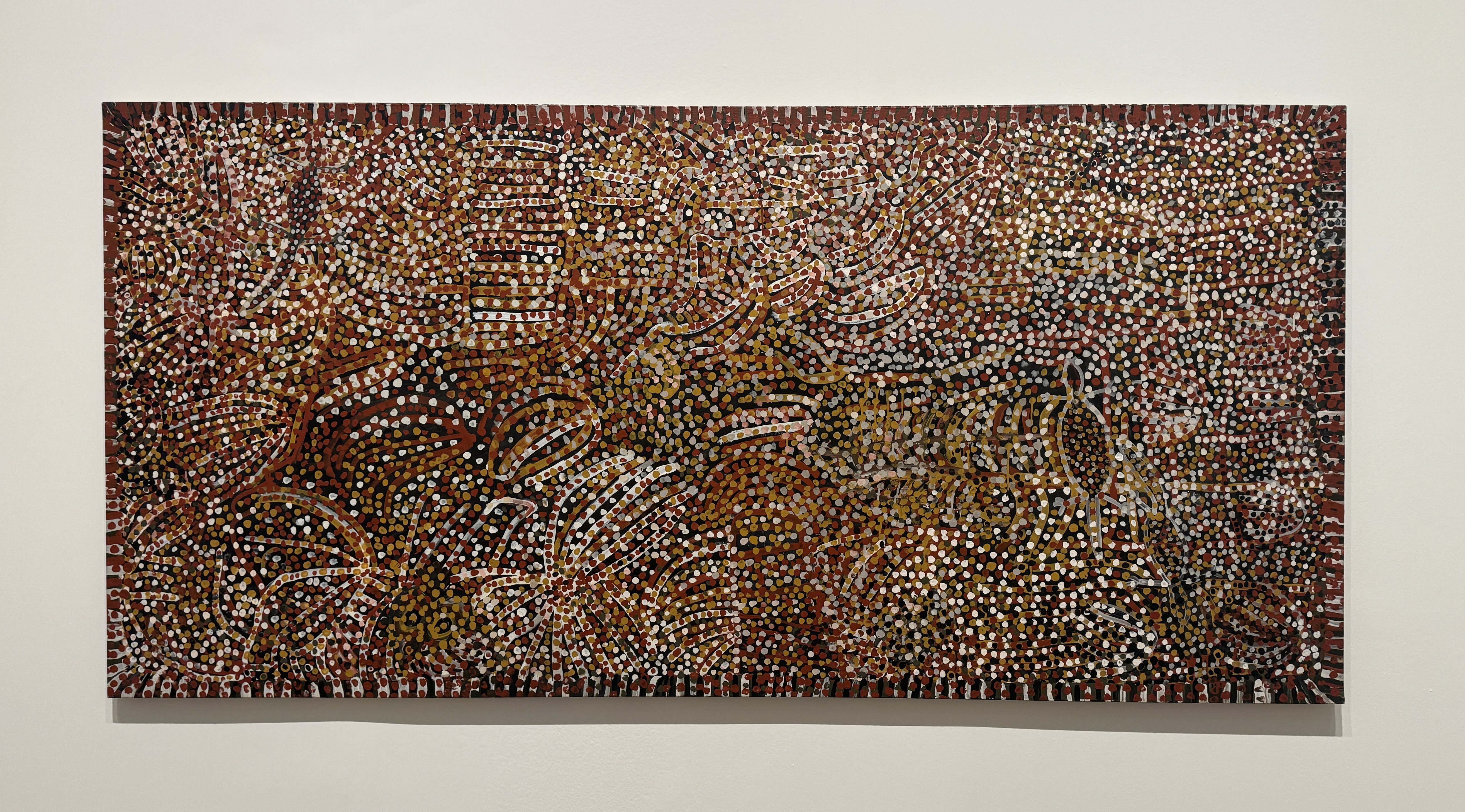

I stood in front of Ntang. A medium-sized, vertically-oriented canvas covered with dark green, beige, orange, and dark grey/black paint. At first, it appeared to be covered entirely in dots. Looking closer, there were beige networks running underneath the dots with large pools of black in between the lines. The painting was simultaneously light and dark in color and, along with the layering, gave a sense of accumulation. Layering. Many of her paintings are like that. Taken together, they read like a topographical map sketching a network of paths and tracks extending across the land of the canvas, a sense that was underscored halfway through the show when an entire wall had an aerial photo of Alhalker, its red dirt pocked with green and yellow-white vegetation.

The paintings grew bigger. The form loosened. There were paintings of lines on a white background, some straight across, some that criss-crossed each other. The colors were simpler and darker, more like the earth, with browns and reds and blacks, until Yam Awely (1995), a painting that takes up an entire wall. The lines reminded me of heatmap tracking paths. “Awely” has two definitions: It’s both a women’s ceremony and the designs and songs associated with the ceremonies. The women of the Anmatyerr people paint lines on their bodies for these ceremonies and the paintings are drawn from Kngwarray’s experience with them. “These paintings were not at all invested in art historical terms,” wrote Stephen Gilchrist in the essay ‘I am Kam’ from the companion book to the show. And yet, I was. I tried not to be.

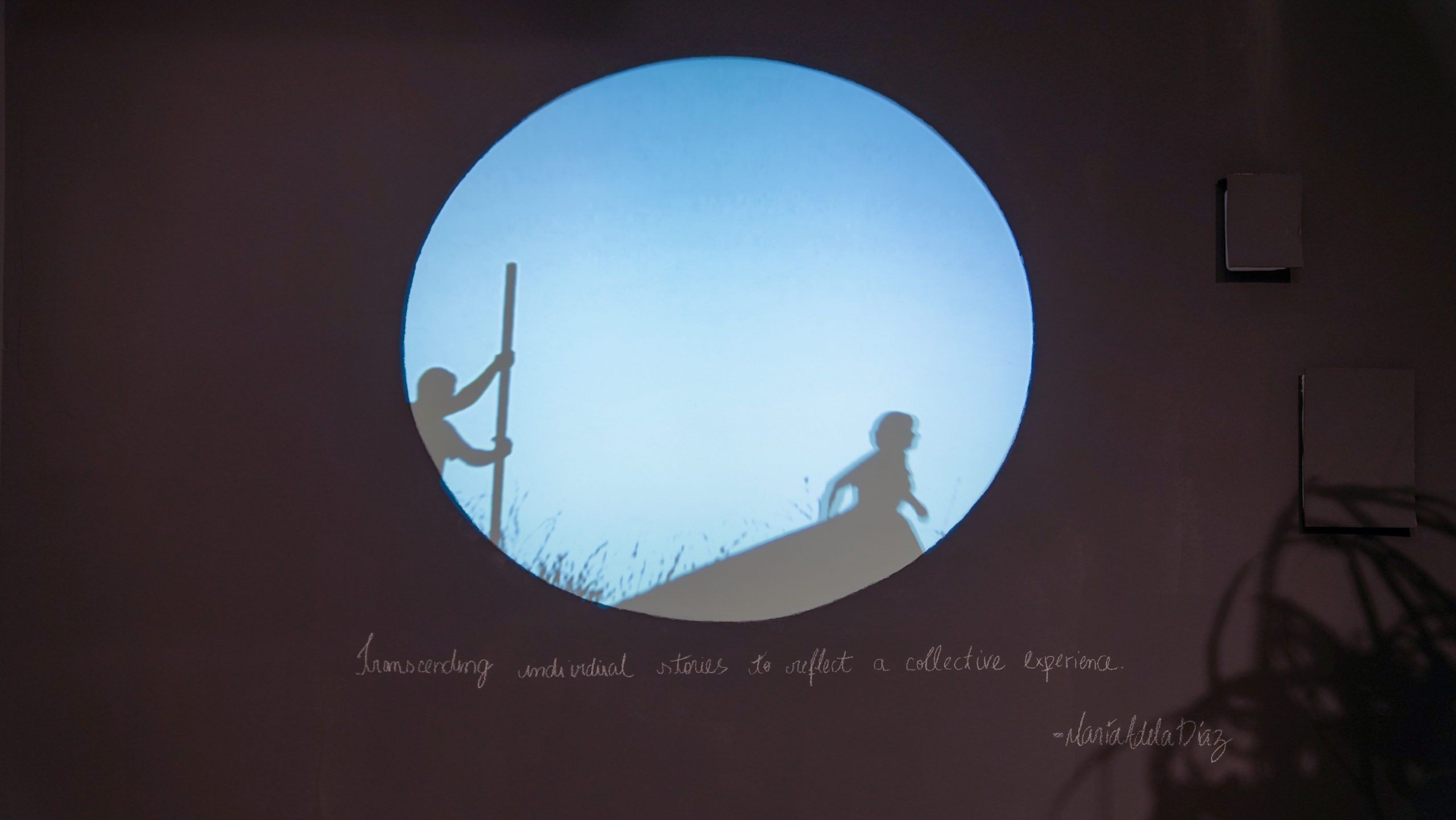

I found Wild Yam VI (1996) in the last room of the exhibit, a large canvas with lines, mostly white and yellow with bursts of pink and purple, running over a black background. As the title suggests, the painting marked something of a return for Kngwarray, “an intentional and repetitive assertion of her identity.” Her entire oeuvre consists of an acute resistance to colonization and simultaneously acts as a love story to her people, her Country. Her work is about identity, yes, but a collective one. Individual identity meant very little to her.

Recently, a feeling of discontent had crept into me, the origin mysterious, though I was aware that feeling untethered at the dawn of your thirties was entirely ordinary. On the train to London, I’d been reading Simone de Beauvoir and couldn’t shake this passage: “I had become a different person, and I should have had a different world about me; but what kind? What was I really looking for? I couldn’t even imagine what it would be like.” Kngwarray and I had opposite problems. She knew what she looked for. She could imagine her world. I was trying to conjure my own, from nothing.

Her life project and mine are not at all the same. And yet, the experience of Kngwarray’s paintings, despite the distance between her experience and my own, has soothed me, has planted its own roots in me, has given me that feeling of being rooted, and it was given to me freely. I became a recipient of her generosity, which she might not say is generosity at all, but simply how the world is, or should be.

“Indiginous art is grounded in the intellectual, cultural and political genealogies of Indigenous people and logically exists outside of the linguistic authority of Western art histories,” writes Gilchrist. “Art is not something removed and separate from everyday life; it is enfolded within it.” Where Hirst’s exhibition had dripped with decades of art historical knowledge, and stood outside of the world on a pedestal erected by the Art world, Kngwarray’s exhibition resisted both.

When I re-entered the Tate this summer, before I walked up the stairs to the Kngwarray exhibition, I wondered if this time I’d be smart enough to make sense of what I saw. Thirteen years ago, I stood as close to Hirst’s art works as I could get until a gallery attendant, always polite, admonished me. Of A Thousand Years, the art critic and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist said that it represented an “ongoing fascination with containment and the crucial difference between being caught inside and looking in from the outside.” I suppose, without knowing, I was looking to see which side I was on. But even now, I see, I am still trying to figure it out.