[drop-cap]

One need not have a particularly apocalyptic imagination to be reminded that even the most famous artworks can become inaccessible at any minute. Michelangelo’s David was bricked up for the entirety of World War II, and what was once miraculously revealed in Carrara by the artist’s hand vanished within a structure reminiscent of Paul McCarthy’s monumental butt-plugs. Simon Hantäi’s Écriture Rose, in uniting the force of interminable text to the pursuit of pure color and thus inciting André Breton’s disapproval of this twist on automatic writing, nevertheless survived his excommunication from surrealism and for a long time was prominently displayed in the Pompidou. That is, until Emmanuel Macron requisitioned it for his own office, to hang (as one can see on the Internet) behind an ostentatiously piled escritoire, thereby transforming the painting into a metaphor for bureaucracy transcended, sublimated or sublated in the pursuit of democracy. Yet making it all but inaccessible to the common viewer.

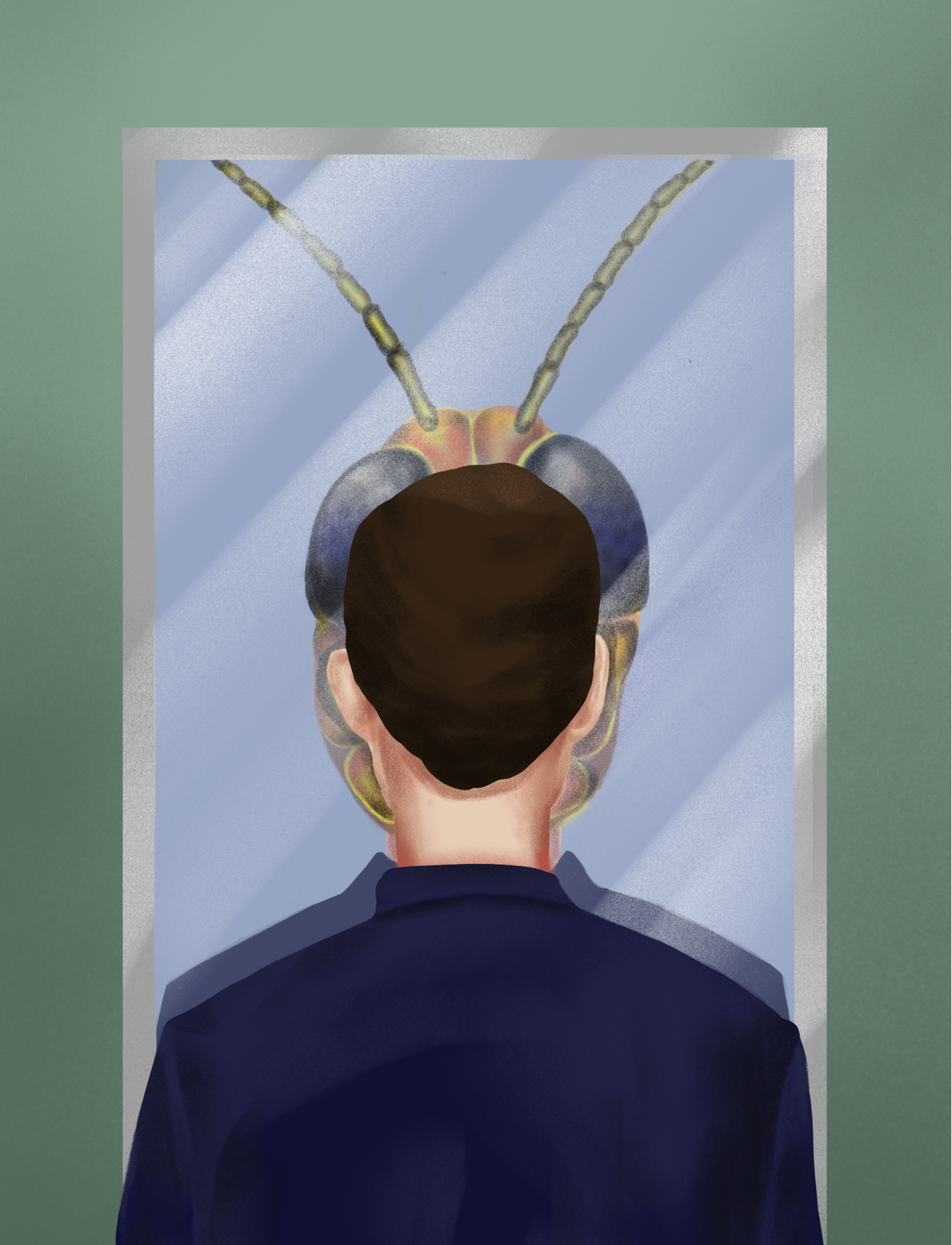

But what about that other, less dramatic form of the disappearance of art: the way in which our very consciousness fails its presumed immortality? Once faced with the actual David, how long are we compelled to stay with him, and how long does he stay with us? What is the emotion (shame, sadness, indifference, resignation?) that accompanies us when we speed by, skip or reluctantly leave a celebrated sala? For some art, this feeling is built in. Signorelli’s frescoes in Orvieto—tableaux of the end of the world and the reign of the anti-Christ—are an art that prefigures the end of all things, with the very painting itself perhaps the first to go. But Freud went one step further to show how this apocalyptic end of art was a banal thing after all: when he later tried to describe these frescoes to a friend, his inability to remember the name “Signorelli,” and the various replacements and repressions that got caught up in the art of his forgetting, became the core of his Psychopathology and Everyday Life. Unavoidable and even productive, then, is the disappearance of art from the forefront of our attention, despite the fact that Google can now be called upon to resolve a tangled recollection.

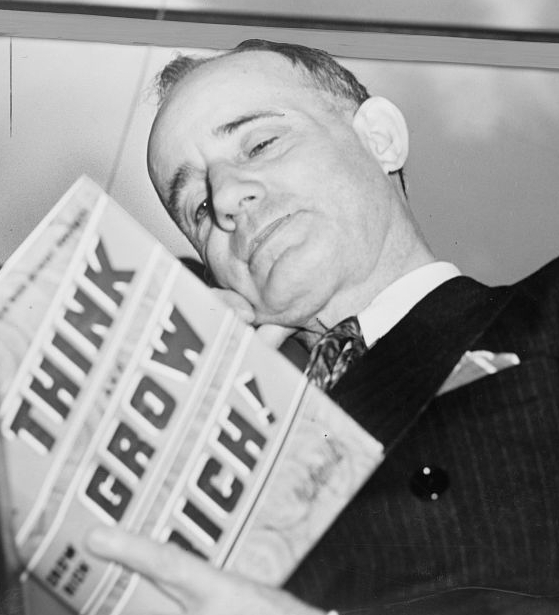

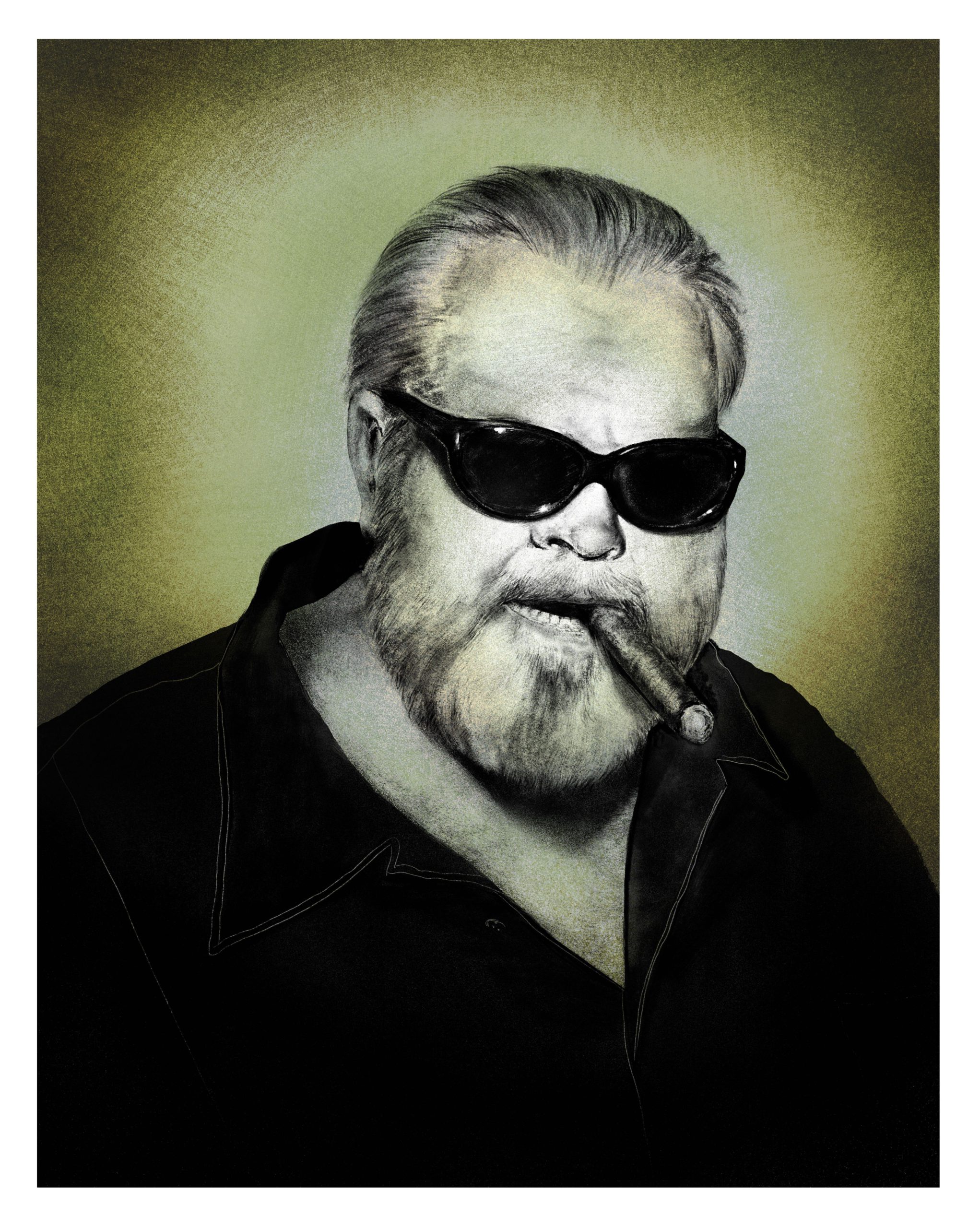

Fast forward to all manner of ephemeral art forms that emerged from the shadow of Freud’s great disadumbrations. The neo-Dada movements of Nouveau Realism and then Fluxus popularized this art of the fleeting and insubstantial moment, arguably set into motion by the work of Daniel Spoerri, who died last fall. Spoerri was known primarily for his “trapped tables”—glued and bronzed remnants of everyday repasts, a quite literal reinterpretation of Dutch still lives and memento mori—and later extended this art of everyday eating into conceptual restauranteuring. While in Tuscany this fall, I had planned to visit his sculpture garden in Seggiano, half expecting to see him tramping around the premises, since it had become his home since 1997. The type of art that Spoerri helped popularize makes us more aware of the tenuous mysteries of presence, so it is perhaps fitting that the guidebooks will still claim that he might be seen among the bronzed assemblages of the property, even if he is no longer among the living.

Over the years I’ve become a student of such Italian roadside attractions, and have hitchhiked, bussed, or drove to what we would call “tourist traps,” leading me to reflect on the fact that, if Spoerri’s garden is an extension of his trapped tables, then I am on the menu.

A recent book by Paolo D’Angelo connects this tradition of Italian roadside art to what we would call land art, much of which plays with the dynamic relation between its extreme remoteness and the publicity mechanisms at the centers of art production. But whereas much land art in the U.S. is a product of post-1960s minimalist and conceptual art, and as such a refiguration of industrial practices, the Italian tradition is much more impacted by the vernacular richness of surviving fine-arts sculptural skills. If U.S. artists tended to appropriate the tools of modern construction to create monuments redolent of prehistoric or posthuman time, Italian sculptural artists have tended to embrace more artisanal practices to approximate the Baroque folly. As D'Angelo notes, the model is Bomarzo, a Baroque garden of stone monsters somewhat resembling an ancient mini-golf course, abandoned for over a hundred years until rediscovered by the surrealists in the 20th century. The Colossus of the Apennines in the hills above Florence is another similar example of a Baroque-era garden fantasy. Blink for a moment, and you’ll miss the stop for it, and a surly bus driver will take you two miles down the other side of the mountain, despite entreaties to stop.

Daniel Spoerri’s update of the Baroque sculpture garden is a straight shot from Signorelli’s Orvieto, if by straight you mean through the torturous logic of the unconscious, as the hour and a half drive is a series of hillside twists and turns to the edge of Val d’Orcia, in the shadow of the dormant volcano Amiata. Upon reaching the property, you are welcomed by the sign “Hic Terminus Haeret.” One can perhaps translate this sign as the oldest fiction of topographic presence, the ur-sign, which is paradoxically always true: “You Are Here.” And yet, even in this apparently simple statement there is deception afoot. We could more directly translate it as “Here is the end,” or “Here inheres the end,” referencing the tourist’s achievement of sought-after destination (because despite the importance of “chance” to Spoerri’s work, it is highly unlikely that anyone would happen upon the garden “by accident”); or it could also imply Spoerri’s decision to live out retirement in the garden. Yet, we are reminded by the travel booklets that the phrase is pulled directly from Virgil’s Aeneid, Book IV where Aeneas finds himself entranced by the hospitality of Queen Dido: we know in that case, the notion of staying on in Carthage and living out the rest of his days with Dido is not only ill-fated. It is non-fated. Aeneas has bigger historical fish to fry. He needs to found Italy itself! The fate of Rome and perhaps Spoerri’s garden, however much it is imbued by rough Etruscan charm, depends upon Aeneas ignoring a sense of easy terminus.

Terminus also means boundary in Latin, and in fact is the name of the two-faced god of boundaries, similar in bi-countenance to Janus. Bluntly, then, “Hic Terminus Haeret” is a statement of ownership. But, it also entails a splitting. And here, in a sense, inheres the here: any designation of “here” simultaneously creates a non-here. One goes from here to there, not to cross space, but to maintain “hereness” across time (the “ere” that is the essence of the “here” inside every “there”). In this spirit of circular logic, the first thing you see on the property, after this riddle of “hereness,” are street signs emblazoned with palindromic poems by André Thomkins.

You are also given a more standard map of attractions upon entering Spoerri’s garden. On the back of a cartographic plan with obligatory pin markers, each of the 115 sculptures is rendered by a small drawing, accompanied by artist name and date. By this detail, the map makes an explicit connection back to Spoerri’s book Anecdoted Topography of Chance, his literary, proto-hypertext experiment, spinning commentary from each object on a table trapped in October 17, 1961, and accompanied by similar hand-drawn miniatures. This attempt to find the infinity of reference in a single, momentary detail accompanies Spoerri’s work throughout his career. One can even visit, in bronze and a-tilt upon a small wooded hill at the center of the property, the origin of this anecdoted table: room number 13, 5th floor of the Hotel Carcassonne, 24 Rue Mouffetard, Paris.

What soon becomes clear to the visitor is that the garden’s sculptures are pointedly non-monumental follies. If the garden’s spirit of whimsy comes from the tradition of Italian Baroque, the overall aesthetic is of French brut. Everyday and discarded objects collaged into bizarre combinations litter the landscape. You will encounter many demons, saints and “skinny nightmares”—the seeming guardians of the garden—composed simply of hat racks, doll heads, chairs, and skeleton parts cast in bronze. Even the circle of unicorn skulls that overlooks the valley, Spoerri’s Umbilicus of the World (1991)—one of the sites the attendant at the gate urges you to see—holds close to the ground. Its array of bronzed narwhal horns extends from the top of cow skulls and points to the sky, inexplicably held in place by disembodied gauntlets. Walk past this circle of assemblaged unicorn heads to Giampaolo di Cocco’s The Art of Dying (2006) at the far end of the property. This is perhaps one of the more moving installations, in which the remains of elephants or mastodons seem to be in the process of returning to the earth, while tin cameras at the edge of this presumably archeological site seem to mock the ghoulish tourist gaze (and allow us to imagine the dinosauric end of our own camera era). Up the hill from this, an army of geese bear down upon you, with three menacing and faceless drummers marching in their wake (Olivier Estoppey’s Dies Irae, 2001).

For all the reminders of death that abound in Spoerri’s sideshow congeries of memento mori, the ultimate aim is one of conviviality. D’Angelo reminds us that Spoerri, as would befit Fluxus and Nouveau Realism, conceived “l’attività artistica come un fatto corale.” All these pieces are born of some kind of friendship with the artist; one could not “submit” or “be commissioned” for inclusion. Except for a curious addition from the poet Goethe, these sculptures are all made by his immediate contemporaries and companions. Art is a “choral fact,” one made among friends for the purpose of keeping friends, and is not constrained even by the coterie of a specific movement. In fact, I believe only one remaining member of the original Nouveau Realists—Jean Tinguely—is included in the garden, and that may be because his wife’s work—Eva Aeppli—has a more prominent presence on the grounds.

I spend my last bit of time in the garden squinting at the map numbers trying to find the Tinguelies, retracing my steps so many times that a curtain suggestively caught in the branch of a persimmon tree started to present itself as a plausible candidate. However, since Tinguely is known for his hectic and jerky electro-mechanical assemblages, his installations require some retreat from the elements. As if emulating one of Tinguely’s mechanical beings, I constantly tack back and forth between map and world, bumbling around the periphery until I find this hidden retreat. In a small back room of the restaurant bar, a pedal activates a bizarre punch-and-judy machine that memorializes Othello and Desdemona’s tragic relationship. This métamatic collaboration between Tinguely and Aeppli may remind us that not all relations are fuzzy-wuzzy, and that friendship remains an ideal that is admirable but difficult to maintain.

There are many others that I failed to find, or I only learned about once home. Sculptures only visible by searching trees with a telescope?! A skull chapel?! A ghost head from Michelangelo’s marble pit?! Stateside, I flip through a lavish Austrian catalog of his work from 2021, ending with an account of a piece in the garden by Nam June Paik, which I also missed, and for good reason. When Spoerri asked for an inclusion from Paik, these instructions for the monument were relayed to Spoerri by Paik’s gallerist while he was in bad health: “Tell him to make something as big as the Eiffel Tower!” Consequently, Spoerri took the smallest tourist trinket of the Eiffel Tower he could find, and put it on a plinth. The text on its metal plaque (is it in comic sans?) is bigger and much more visible than even the tower itself. From afar, this Eiffel Tower would probably disappear into the marble expanse of the plinth’s cap.

I actively avoid “going to the Eiffel Tower” in Paris. And yet, I feel like I need to return to Spoerri’s Il Giardino, for the express purpose of finding this one.

All photos of the garden are by the author.

Sources

D’Angelo, Paolo. Andare per Parchi Artistici. Bologna: Il Mulino, 2024.

Brugger, Ingried and Veronika Rudorfer. Daniel Spoerri. Vienna: Kunstforum Wien, 2021.

Spoerri, Daniel, et al.An Anecdoted Topography of Chance. Trans. Emmett Williams. London: Atlas P, 1995.