Author’s Note: This article was written in March 2025. By now, many of my students’ access to utilities—e.g. solar power, telecommunication service—has been dramatically curtailed. Due to the increasing pressures of the war, class has petered out into personal sessions and occasional lessons. Most of the students live in Gaza City and are currently under evacuation orders as a result of Israel’s land campaign to remove residents from their homes.

[drop-cap]

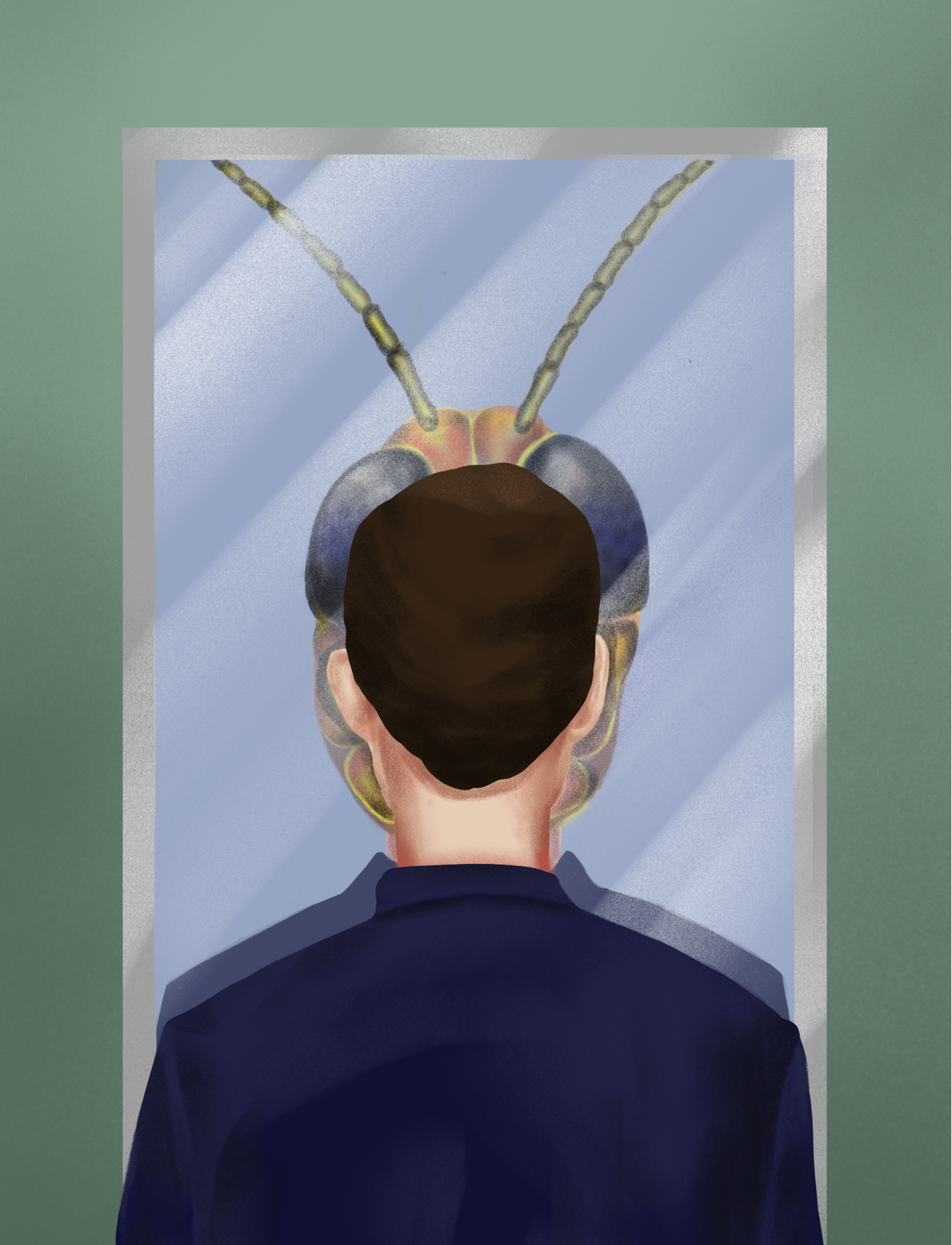

If you’re learning English, you’re unlikely to come across a word like “devastation” until you’re pretty far along in the endeavor. Maybe not even until you’re approaching fluency. I’m on the lookout for low-frequency words like “devastation” whenever I’m reading articles out loud with my intermediate-level students. “Do we know this word, ‘de-vas-ta-tion?’” I check in. “Yes, we are familiar with the word,” Bassam, one of the students, responds. The class chuckles a bit. We keep reading until we come across the word “rubble.” “Are we familiar with this word, ‘rubble’?” I ask. Bassam, again: “Yes. We know the word ‘rubble’... We are Palestinian…” His classmates laugh a bit harder.

For a few hours every week, I teach online English classes to Bassam and a handful of other teenaged to middle-aged Palestinians. Some are stuck in the Gaza Strip, others have managed to flee to Egypt. Class is held over Zoom, and attendance varies depending on the students’ internet access. (Some have to walk 40 minutes for wi-fi.) Israel controls much of Gaza’s electricity supply. So when Israeli authorities cut off electricity—as they have done intermittently since the start of the war—students rely on solar power for fixed-line wi-fi. When there’s no wi-fi, students rely on digital SIM cards provided by international aid organizations, which makes them shrewder about data usage (like keeping their cameras off and muting themselves until it’s their turn to speak). During bombardments, they tune in from darkened rooms in darkened apartment buildings. Evidence of population density is kept to a minimum in spite of the fact that Israel’s F-35 fighter jets are equipped with infrared cameras for target detection. When students don’t show up to class, one assumes it’s for lack of internet connection, but a few inshallahs are said on their behalf just in case.

All of my students are remarkably tech-savvy. They’re better versed in the applications and limits of ChatGPT than I am, and I occasionally catch them using it when I’ve assigned them to write a paragraph in the future perfect continuous tense. They know many of Zoom’s more esoteric settings and features. They know how to embed Google transcription and translation features into their browser windows. They use VPNs to pirate international television shows otherwise unavailable to them, like Netflix’s Mo. Almost all have aspirations of joining the tech industry.

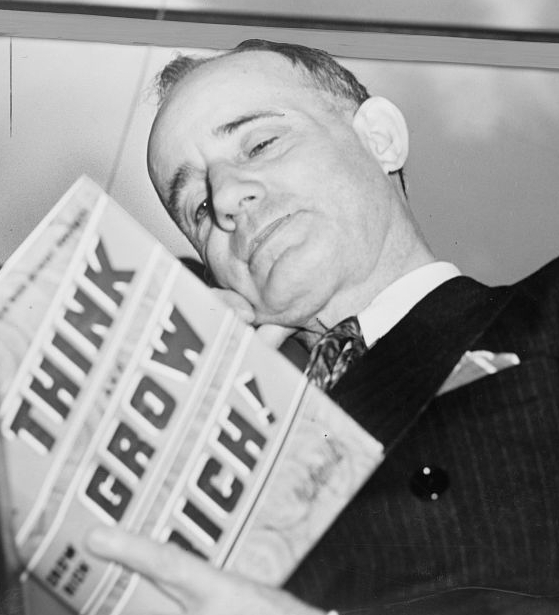

But I’m old school. I encourage them to read books in their off-time. Books, too, are scarce in Gaza. A student told me that many of the Strip’s inhabitants hide out in ministries or schools during bombardments and resort to burning books for fuel and warmth. But when I asked if they had access to any books in English, several students, none of whom knew each other outside our classroom, mentioned Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich (1937). Another two had read Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki (1997). I had never heard of either. Apparently, both Hill and Kiyosaki are well known in Gaza and the West Bank, thanks in part to a popular refugee influencer, Kazzaz Mindset, who has encouraged his followers to start their journey of escape and success with Napoleon Hill. When I asked friends here in Los Angeles if they’d heard of Hill, they told me that Think and Grow Rich was as storied a prison read as the Bible, the Quran, or Iceberg Slim. So I ordered a copy of each book from the library and looked into both men.

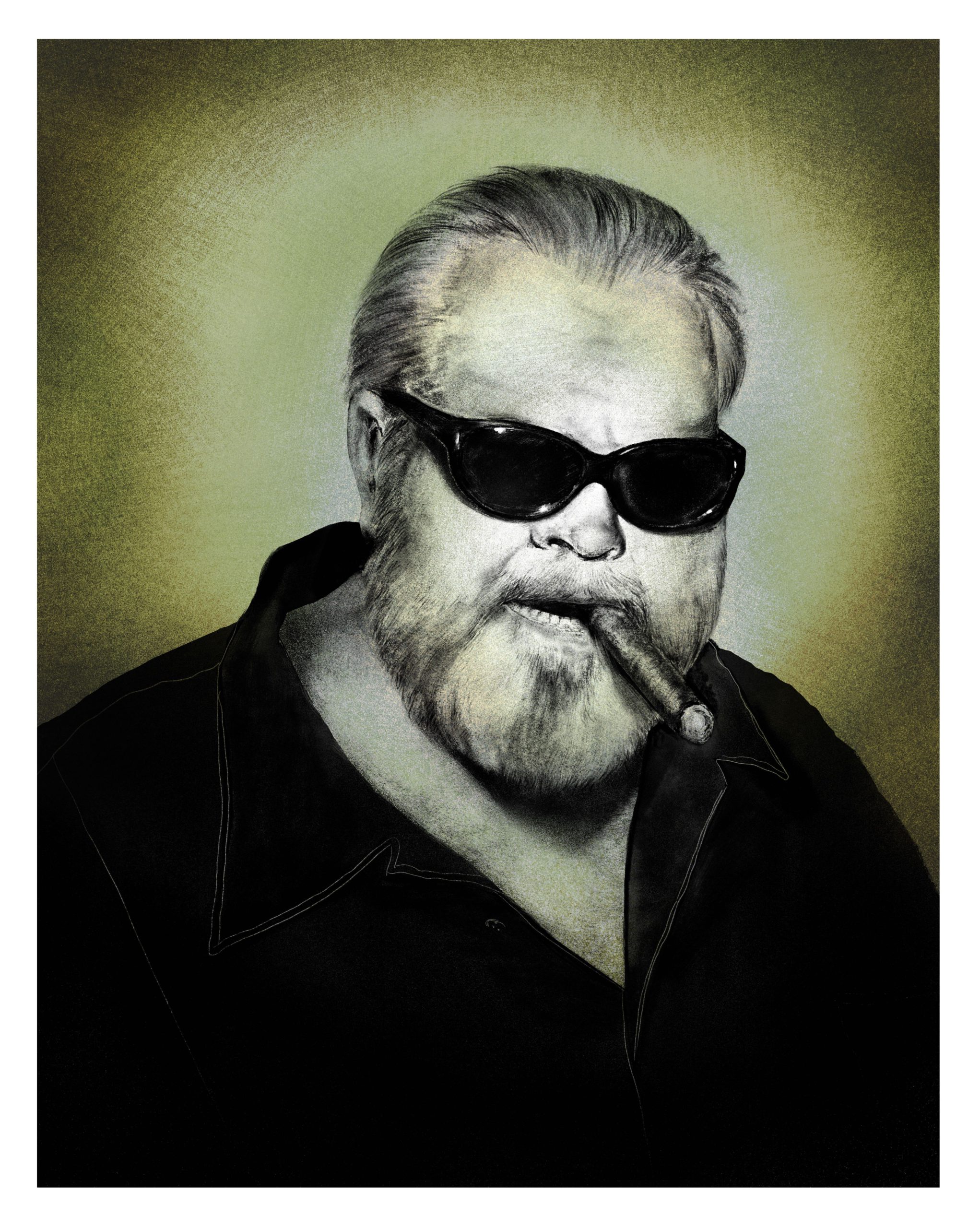

Napoleon Hill, it’s pretty safe to say, was a sociopath. His origin story, as presented in Think and Grow Rich, differs from reality in just about every meaningful way, a fact that even biographers from the Napoleon Hill Institute admit. “Poverty is the richest experience that can come to a child,” Hill wrote, reflecting on his upbringing. He spun a JD Vance-style, hickory-ass yarn about emerging from a moonshine quagmire in Appalachia, drying himself off, and escaping a family of cross-eyed morons with corn cob pipes hanging from toothless gums. In reality, Hill’s father was a dentist and his grandfather a well-to-do printer.

But it’s more fun to run through the man’s rap sheet than his bio. Hill maintained he got his first big break after alerting his boss at a coal mine to a vulnerability in his safe: The dial was easy to manipulate without knowing the combination. Impressed that Hill warned him instead of making away with the contents of the safe, the boss gave him a promotion. In reality, Hill earned said promotion by helping to clean up and cover up his boss’s murder of a local Black bellhop—think of Belinda’s dilemma in season three of The White Lotus. But being a good employee was never going to lead to the riches he sought. So Hill turned to entrepreneurship and theft. He opened various phantom organizations and charities to raise money then ran off with the proceeds. In one instance, he hired local schoolchildren and Boy Scouts to collect donations for a prison education charity he’d founded. After the children had canvassed the whole region, Hill collected the funds and skipped town. He repeated the same scheme a couple of times, each of his fraudulent organizations bearing a vaguely entrepreneurial name like “Success Unlimited” or the “Philosophy of Achievement Foundation.” Later, Hill opened a “pay-to-work” university, whose students paid tuition only to spend most of their time working as unpaid chauffeurs for local tycoons. When one student, a German immigrant, took issue with the arrangement and accused Hill of fraud, Hill reported the student to the FBI and got him locked up for the remainder of World War II under the Espionage and Sedition Act.

At home, Hill had a medically deaf child, Blair, whom he refused to teach sign language, believing that doing so would only accommodate the boy to his deafness rather than help him overcome it. Deafness, Hill believed, was an affliction for those possessed of a “disability mindset,” or for people who just didn’t want hearing badly enough. Its remedy, Hill maintained, was his own spin on the technique of autosuggestion: using self-hypnosis to embed one’s desires and goals in the unconscious. Miraculously, Blair did alright for himself despite his father—so much so that, when the elder Hill went broke and needed a loan to write Think and Grow Rich, it was Blair who saved Napoleon from financial ruin and gave him money to write the book. Years later, when Blair caught wind of the monumental success of Think and Grow Rich, he asked his father to pay back the loans he’d extended to him. The elder Hill refused.

The more I looked into Hill, the more a picture emerged of his persona: a Brooks Brothers edition of Robert Mitchum’s Harry Powell in The Night of the Hunter. The two share a psychedelic hypocrisy; so blatant in its misdirection that it can destabilize your sense of up and down, right and wrong. In suspension, you’re more vulnerable to their hokey, hypnotic gospel.

It’s not surprising that Hill was persuasive in person, able to convert legions of Boy Scouts and other young hopefuls into his personal bagmen. But it’s a bit surprising that he is persuasive on the page too. Think and Grow Rich is not badly written (perhaps thanks to Hill’s third wife, Rosa Lee Beeland, who is widely believed to have been its true author). But the book doesn’t tell us about how to run a scam at all. What a shame. Instead, it’s an extended meditation on how to get wealthy the right, clean way—through attitude, will, virtue. Hill frames the book as the result of a project allegedly commissioned by Andrew Carnegie himself and painstakingly carried out over the course of 25 years, involving interviews of 500 of America’s richest men. Through interviews, Hill arrives at the secret to wealth accretion: focused positivity helps one achieve clearly defined goals. If this sounds like a conclusion that wouldn’t require a quarter century’s worth of research, you’re right. Hill never undertook the survey at all, and he never met any of the men he claimed to have interviewed: John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, Charles M. Schwab. He never even met Carnegie, whom he quotes at length.

Was the book better for having come from Hill’s imagination? Potentially. But I’m no judge of the genre. I’ve always assumed that what these self-help books really offer is affluence mimicry or proximity illusion. You get a sense of wealth by osmosis, the kind you get by, say, signing up for a Wall Street Journal subscription or downloading a Coinbase wallet. Think and Grow Rich was released shortly after the worst years of the Great Depression (and a year after the breakout success of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People). Its appeal, now as then, is greatest among readers for whom making money is near impossible for reasons beyond their control. But they can still make plans about how to make money someday. You can mull over it, tinker with it like a recipe write-up for a meal whose ingredients are not yet in store, and hope that they will be someday.

Robert Kiyosaki’s advice in Rich Dad Poor Dad is a bit more concrete than Hill’s. The book offers more specific financial planning wisdom. But Kiyosaki is a moron where Hill is a sociopath and the book suffers accordingly. A look at his life makes you wonder whether he’s all that good at financial planning himself. Similar to Hill, Kiyosaki’s success has a patchy provenance. But instead of abusing the trust of the poor, Kiyosaki goes elsewhere for OPM (Other People’s Money). Much of his success has been built on strategic defaulting and bankruptcy arbitrage. “Living debt-free is the worst advice you could give,” he writes, because, “if I go bust, the bank goes bust… Not my problem.” Kiyosaki’s company, cleverly named Rich Global LLC, has nearly $26 million in liabilities and $1.8 million in assets. Kiyosaki boasts that he is over a billion dollars in debt. “I use debt as money and I don’t save cash because in 1971, [the year Nixon abandoned the gold standard] the dollar became debt.” On his podcast, Kiyosaki refers to the Federal Reserve as the world’s largest criminal organization. My stomach turns when I contemplate Rich Dad Poor Dad’s popularity (over 30 million copies sold). The man doesn’t write or speak; he leaks.

Neither of these books, of course, are among America’s proudest exports. But they could be our most emblematic. What English-language books would make the best use of my Palestinian student’s time? I’ve never really contended with the utility of self-help literature, but I’ve settled, lazily, on the idea that the genre might be of anthropological use to them. Most of them are casting westward, and Kiyosaki and Hill are, ironically, perfect guides to some essential elements of Americana—bootstrapism, prosperity theology, con-artistry, self-development, motivational speaking, that whole Duke and the Dauphin thing.

It’s easy to guess the politics that attend Hill’s and Kiyosaki’s brand of optimism. Leftists would be correct to see their logic as comorbid with the “If you’re poor, it’s your fault” type of thinking. And, yet, the less a society built around these values—self-determination, independence, egotism—has done for you, the more it’s mandated that you embody these values. You need to buy in to build up. Choosing to believe in economic determinism in these conditions seems like it would amount to forfeiture.

In the case of my students, solidarity is not an option. Israel’s stated aim is to so thoroughly de-compose Gaza’s political infrastructure, and so thoroughly blanch its land, that Palestinians will be unable to rebuild a political system in their own image. Escape is the only option. As preposterous as it is to think of people reading Hill’s hogwash methods of “auto-suggestion” amid the rubble—as if it could help anyone in a war distinguished by its utter political immovability—some form of optimism seems non-optional. And in a world this broken down, this broken apart, the Hills and Kiyosakis have a monopoly on optimism.

“Do you read any books not about money?” I asked my students after a lesson. They laugh, but the arrogance of the question only occurs to me after I utter it. Small talk before or after class never feels that small; everything finds a subtle way of relating back to the enormity of suffering in Gaza. Alarming details are casually dropped. Whenever we discuss IELTS or Duolingo exams, Bassam slips “evacuation” instead of “evaluation.” When he discusses his errands for the day, he says he bought 25 kilograms of flour for $150 USD. The same amount would be about $55 in the US. Sarah, who has a graduate degree in engineering, discusses her tech job at a European company. She is one of very few of her peers who has a job, not to mention one in tech. But the job only earns her four US dollars an hour. Anas, Sarah’s classmate, observes my reaction to Sarah’s salary admission. “You see why we read these books,” Anas says.