[drop-cap]

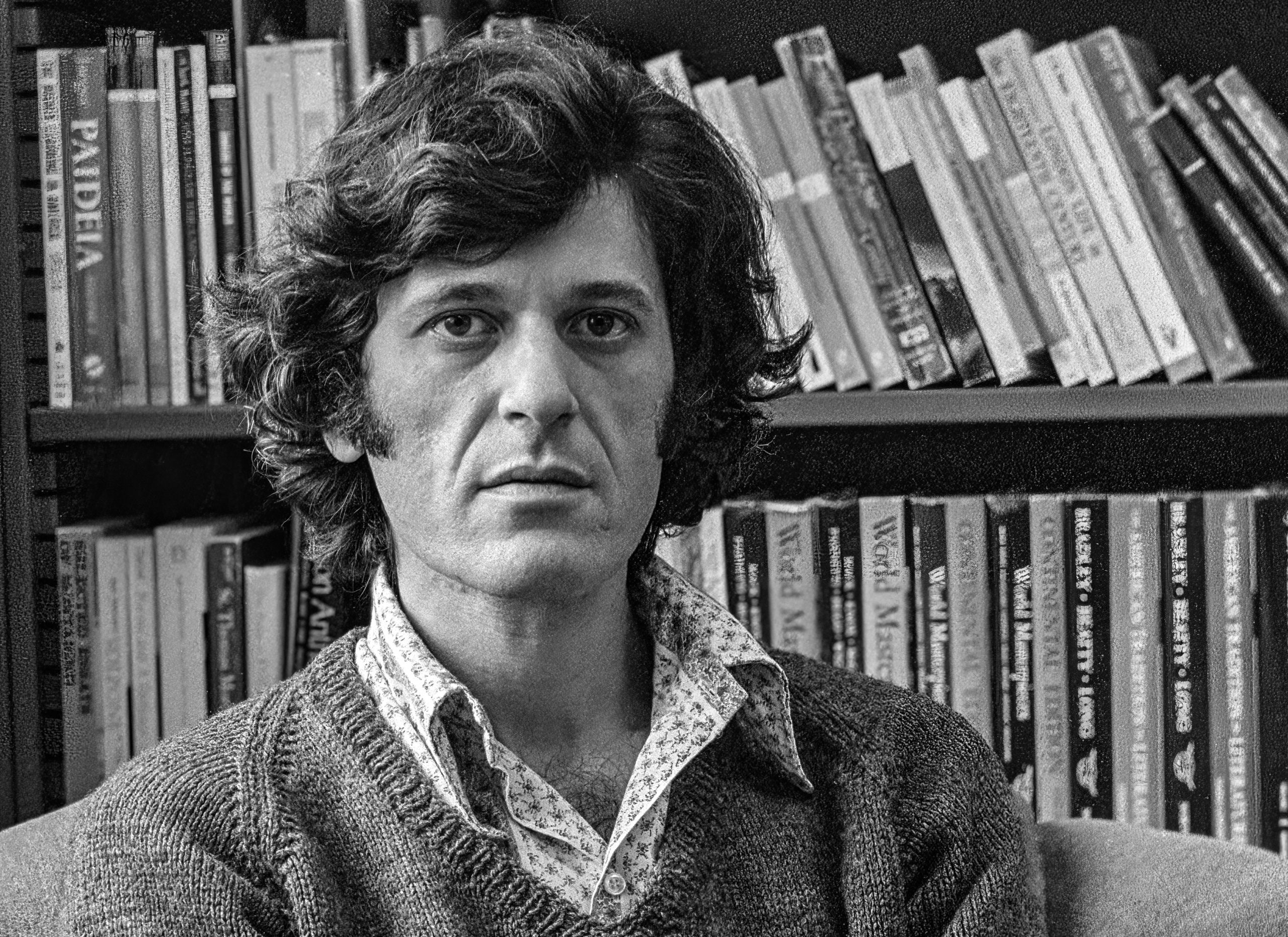

“It all started with a joke,” said Joseph Beuys about the origin of his 1985 installation Plight, wherein he covered the interior walls of two rooms in London’s Anthony d’Offay Gallery with 284 rolled-up cylinders of felt. Beuys made the joke on a scoping visit when loud construction was going on all around the building. When the gallerist mentioned the idea of hosting Beuys’ upcoming show in a quieter temporary space, the artist suggested, half-seriously, that he could make a “muffling sculpture” to keep out the noise. When the show came around later that year, the construction might have been over but Beuys returned to his first idea for Plight, a work of “insulation from outside influence of danger, of noise, of whatever,” as he told William Furlong in October 1985 for the Audio Arts cassette magazine. In the first felt-lined room he placed a closed grand piano, a blackboard showing an empty musical staff, and a thermometer. He kept the second room empty.

Plight was purchased by France’s Musée National d’Art Moderne in 1989, and set up in a purpose-built replica of the d’Offay gallery nested into the fourth floor of Paris’ colorful, lego-like Centre Pompidou. Plight and the museum’s entire permanent collection of modern and contemporary art—the second biggest in the world—were taken off view in March of last year; following a Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition which ran until September 22, the iconic building fully shuttered for a major renovation expected to last until 2030. Indeed, it took around the same amount of time, from 1972 to 1977, to build from scratch the Renzo Piano and late Richard Rodgers-designed original. The Pompidou’s equally sprawling and popular library (it was originally allotted more floor space than the museum’s collection) has also closed, along with the center’s performance and movie theaters.

During a visit to the collection on the day before it was taken off view last March, I returned to Beuys’ Plight, an installation born in response to disruptive building works within an institution about to embark on its own massive facelift. You enter the artwork by ducking under a low entryway, a subtle means of disturbing the comfortable upright posture of a strolling museum-goer. (Once you straighten up, you are more or less penned-in.) A waist-high glass partition keeps you from advancing further into the installation and the low entryway means a glance backward only puts you face to face with a wall of brownish-gray felt. Just like that, you’re transported from a museum into the self-contained domain of an artwork.

In simple yet obscure trappings, with the drab, felt-covered walls, the solitary black piano, the blank blackboard and the barely discernible thermometer, Plight intuitively activates more than just the sense of sight. Most striking is the room’s wooly warmth, the immediately distinctive smell of felt, and the way the noise of the crowded museum, as Beuys had promised, is muffled almost to silence.

Beuys described the installation in terms of his transformative vision of art, namely that it could lead people to “develop even more senses.” What would that look like? For Beuys, who often spoke of an “expanded concept of art” encompassing society and the individuals in it, a sixth sense would surely be creativity, i.e., the possibility for each of us to contribute to the “social sculpture” of life on earth. We could contribute by planting a tree (like the 7,000 oak trees Beuys and volunteers started planting in Kassel, Germany in 1982) or launching a political movement (Beuys was a founding member of the German Green Party). Beuys saw these creative acts as the way forward for art after modernism, broadening the scope of “art” and making it the “science of freedom,” as the critic Heiner Stachelhaus noted—a process to achieve self-determination at every scale.

Ever the alchemist, Beuys said that he tried to “use material which is transformable into psychological powers” to spark those “not aware of his or her creativity potential.” On repeat visits to Plight, I came to see its empty-but-for-felt second room as the Beuysian sixth sense of creativity made tangible. While originally accessible, the second room at the Pompidou was only visible from afar, and just partially through the low rectangular opening in the first room’s far wall. That empty, just out of reach backroom appeared as a dream-like symbolic space leading from my immediate sensory reception of Beuys’ warm, odorous, scratchy materials to my own interior creative impulses.

At first glance, Beuys’ participative, come-one-come-all concept of creativity could seem out of step with the often alien and unyielding art he left behind. Yet what linked Beuys’ inclusive theories to his inscrutable works (many of which are by-products of unpreservable performances) was his desire to provoke and awaken. He wasn’t making art as much as he was experimenting with communication and testing messages to the public. He worked at the frontier of expression. While André Breton and Paul Éluard’s Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism (1938) had defined Duchamp’s readymades as “an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art,” Beuys’ stance was that the dignity in human choice and action was already on par with any sacredness ascribed to art. No elevation needed, just awareness. “The formation of thought is already sculpture,” he said, just like metal strewn around a room, tallow caked upon a chair, or felt hung on a wall is sculpture, too.

Today, Beuys’ famous statement “Everyone is an artist” may induce an eye roll because it brings to mind a bevy of self-help books and “paint and sip” experiences. However, the essence of Beuys’ proposition—that one’s opinion on the news of the day or the way one gets to work is a creative act shaping the world—goes deeper and is fundamentally disorienting, or re-orienting. It is just as material and at least as disorienting, if you really ponder it, as the strange assemblage of objects Beuys left behind as his artworks.

His messages, both his words and his works, were an imposition—a gauntlet thrown down—as much as an invitation. The calls for greater self determination that defined the post-war decades of Beuys’ artistic output were of a piece with his belief that people could “sculpt” society. It followed from the awareness that thoughts, words, and actions had an impact on one’s surroundings, even leaving an observable mark. For Beuys, this awareness could lead to new artistic gestures on a scale never before seen. For the good of art and society, it should lead to them. Beuys’ pronouncements were similar in tone to another subtly prescriptive slogan making the rounds in his heyday: John and Yoko’s “War is over (if you want it).” Everyone is an artist (whether they know it or not).

The essence of Beuys’ proposition—that one’s opinion on the news of the day or the way one gets to work is a creative act shaping the world—goes deeper and is fundamentally disorienting, or re-orienting.

That particular spirit of empowering provocation was also central to Piano and Rodger’s original plan for the Pompidou. In a recorded conversation between the two architects in 2016, Rodgers likened the building to a spaceship landing in the middle of Paris. In doing so, he placed it in the lineage of gothic cathedrals and Italian civic architecture during the Renaissance. These were structures which ignored any sense of proportionality with their surroundings, soaring and sprawling in the middle of medieval cities, “revolutionary sites” completely unprecedented in size, style, and engineering. It was architecture as an imposition, an approach, Rodgers said, “all about disruption” and “turning the rules of the game on their head.”

As with so many debuts in Paris, the building was at first a cause for scandal. Georges Pompidou, who as president of France from 1969 until his death in 1974 wanted a cultural centre built in the centre of town, quipped to Rodgers and Piano about their winning idea, “Ça va faire hurler”—this’ll cause an uproar. The two architects recounted being wary of telling taxi drivers what exactly they were working on in Paris. Some called it Our Lady of the Pipes (“Notre-Dame-des-Tuyaux”) for its inside-out exterior.

Rodgers admitted their building needed time to be “adopted” by the city, a challenge for all big projects, not to mention for a massive arts space “that was perceived as a building no one asked for” except President Pompidou. At the outset, Rodgers himself was ill-at-ease about their client being one as powerful as a French president under the country’s executive-biased Fifth Republic. Later in his career, Rodgers would face an actual foe in the form of the current King of England, who intervened on multiple occasions to veto Rodgers’ plans for buildings in the United Kingdom.

Ultimately, Rodgers said the Centre Pompidou “integrated into the city in a diabolical and perverse way,” not because it blended in but because it stood out in color and construction. Piano for his part celebrated this as an invitation to the public “to come and see, to not be afraid” and a way to introduce some of the profane into the “sacred world of art and culture.” This would set it apart from typical “pretentious, overwhelming, and ‘monumental’” museums in marble and stone, which Piano said scared him as a child and remained “intimidating places.”

Moreau Kusunoki’s plans are laid out on the Pompidou’s website in sometimes unintelligible corporate speak... Surprisingly, just two simple sentences cover floors 4 to 6 of the Pompidou (where the art is), and they have the tone of a negotiated compromise.

Fast forward to today and the plan of Moreau Kusunoki, the firm that will lead the “cultural component” of the Pompidou’s renovation with a budget of 180 million euros (an amount yet to be fully funded). A separate firm will lead technical work to remove asbestos, upgrade energy efficiency, and repair damages to the building’s iconic exoskeleton. Moreau Kusunoki’s plans are laid out on the Pompidou’s website in sometimes unintelligible corporate speak, but they broadly imply the building strayed from its utopic and open ethos to become a dated labyrinth of the cybernetic era.

Making the point that Piano and Rodgers’s building was conceived at a time when “speed, animation and information dissemination symbolised progress,” Moreau Kusunoki note that we are now faced with “information overload, fragmented attention, and isolation caused by screen time.” While it’s hard to argue with this, it’s equally hard to square Moreau Kusunoki’s stated desire to simplify with the generally head-spinning presentation of its plans, which seek to do things like reveal “new potentials” by “creating the necessary conditions for their successful activation: programme convergence, a variety of layouts, mixing of audiences, accessible spaces and transversal visual relationships.”

Whatever this means, recurrent features of Moreau Kusunoki’s redesign appear to be expanded sitting areas, more observation decks, and more places to consume food and beverages. They do not seem set to counter the trend of information overload and fragmented attention but rather to complement it by giving visitors yet more spaces to eat, drink, chat, entertain children, shop, and see stellar views of Paris. So much so that Moreau Kusunoki are compelled to clarify that “while the cafés in the forum connected to the urban area complement each other and coarticulate, cafés on the various floos [sic] give visitors a chance to appreciate the faraway views and embrace the venue as a whole.”

Surprisingly, just two simple sentences cover floors 4 to 6 of the Pompidou (where the art is), and they have the tone of a negotiated compromise: “The scenography of the Musée National d’Art Moderne on Levels 4 and 5 and the exhibition areas on Level 6 will also be redesigned. These operations will be designed and steered by the in-house architects and scenographers.”

But the euphoric tone returns to note that, on floor 7, visitors will for the first time be able to access the roof of the Pompidou, where a panoramic rooftop deck will be the “highlight of the Centre Pompidou’s vertical circuit.”

Moreau Kusunoki’s co-founder Nicolas Moreau has said of his work process that “the nature of the site environment is always the first thing that feeds the design and helps us to take directions.” But what will this mean in practice for the Pompidou?

Back in 1973, when work was first starting on the Pompidou, a commercial “revitalization” of central Paris also kicked off a few blocks away with the decision to demolish the historic Les Halles food market. Today, there are nine Starbucks and France’s most visited mall within a ten-minute walk of the museum. Looking ahead, Le Monde has reported that eateries in the vicinity of the Pompidou are more worried about the museum’s impending closure than are neighboring galleries and arts centres. One restaurant manager noted with relief that a large hardware store abutting the Pompidou’s piazza will remain open: “Fortunately, we still have Leroy Merlin to attract people to the area.”

Piano and Rodgers originally envisioned the Pompidou as “a cross between Times Square and the British Museum,” as Rodgers recounted in 2007 at a talk celebrating its 30 years. In execution, this dialectic inspiration led them to build a museum that was adaptable, flexible, and in conversation with its surroundings. Importantly, the building wasn’t their attempt at a fixed synthesis of the oppositional forces of pop and art. Rather, it was an adjustable tool intended to give its occupants the means to navigate and balance those forces in the years to come, with the overarching intention to ignite a “little spark of culture” in its visitors, as Piano described it.

Moreau Kusunoki introduces its plans by noting that “the paradigm is reversed” from when Piano and Rodgers designed the Pompidou in the early days of the information age. Back then, the architects had even intended for the building’s facade to be a screen transmitting information to the passing public; they wanted to break down distinctions between traditional museum departments; they wanted paintings in the museum’s library and books in its galleries. The paradigm the museum finds itself in today has shifted to one of screen addiction and content overload in an immediate surrounding dominated by consumerism as leisure. How then will the Pompidou recalibrate itself?

In the parlance of Piano and Rodgers, the upshot of Moreau Kusunoki’s plans seem tilted in the Times Square direction: bleacher seating, cafés, panoramic rooftop deck and all. But the need to update the Pompidou’s bones has created an unprecedented opportunity to rejig its brain. As a basic Beuysian first step, there is still ample time before 2030 for the Pompidou’s management to directly consult the museum’s public on how it envisions the role of a modern art museum in Paris developing over the next half a century. What’s more, maybe a radically inclusive “redesign” could be the simple transition to free admission, at least for the museum’s permanent collection.

The painter Ad Reinhardt cheekily defined sculpture as the thing you bumped into when you backed up to look at a painting. Is the Pompidou’s art collection destined to be the thing you bump into when you back up for a picture of the Paris skyline? In this vein, interesting also would be a vision from the museum’s programmers and curators of how they might utilize the Moreau Kusunoki redesign in 2030.

The paradigm the museum finds itself in today has shifted to one of screen addiction and content overload in an immediate surrounding dominated by consumerism as leisure. How then will the Pompidou recalibrate itself?

A year before the Pompidou first opened its doors, the Dutch art historian Frans Haks asked Beuys if museums would still be needed in the future, particularly in one where we’d all become artists in Beuys’ democratic image. Beuys responded in the affirmative: “People will be able to go to museums again as though they were going to a religious service. They’ll be able to concentrate on the intellectual side of human nature… the very thing that gives man human dignity.” With 30 years of hindsight and the wild success of the Pompidou, Piano similarly stressed in 2007 the importance of a museum trying to create the conditions for an unencumbered encounter with an artwork; without this, he said, “the museum loses its soul.” Beuys’ Plight, with its insulated arrangement of simple material that created both silence and sensation, had a soul-like presence in the large institution that encompassed it—all the more so for being almost unphotographable.

When I stood in Plight the day before the collection closed last March, there happened to be two other visitors there with me, an elderly lady and an elderly man. The man identified himself to us as Paul-Herve Parsy, the Pompidou curator who led the acquisition and installation of the work in 1989. The lady said she’d come to see it again because she didn’t know if she—or Plight—would still be here in 2030. None of the staff I asked that day could predict the fate of the installation after the closure either, not to mention their jobs. Parsy for his part recalled that he had made sure to destroy the wooden crates that Plight arrived in as soon as the piece was unpacked. He’d hoped that way it would never go off view.