[drop-cap]

It's hard to know exactly when it went wrong, but somewhere along the way the whole notion of going to one of New York City’s major museums, even for the kind of blockbuster, much-hyped shows that define an art season, became something of a slog. It wasn’t inspiration or pleasure or joy—certainly not beauty—that was on offer, but obligation: the prospect of seeing something on a gallery wall that you know you should because it was important and improving. You could be forgiven for not lingering long in the museum.

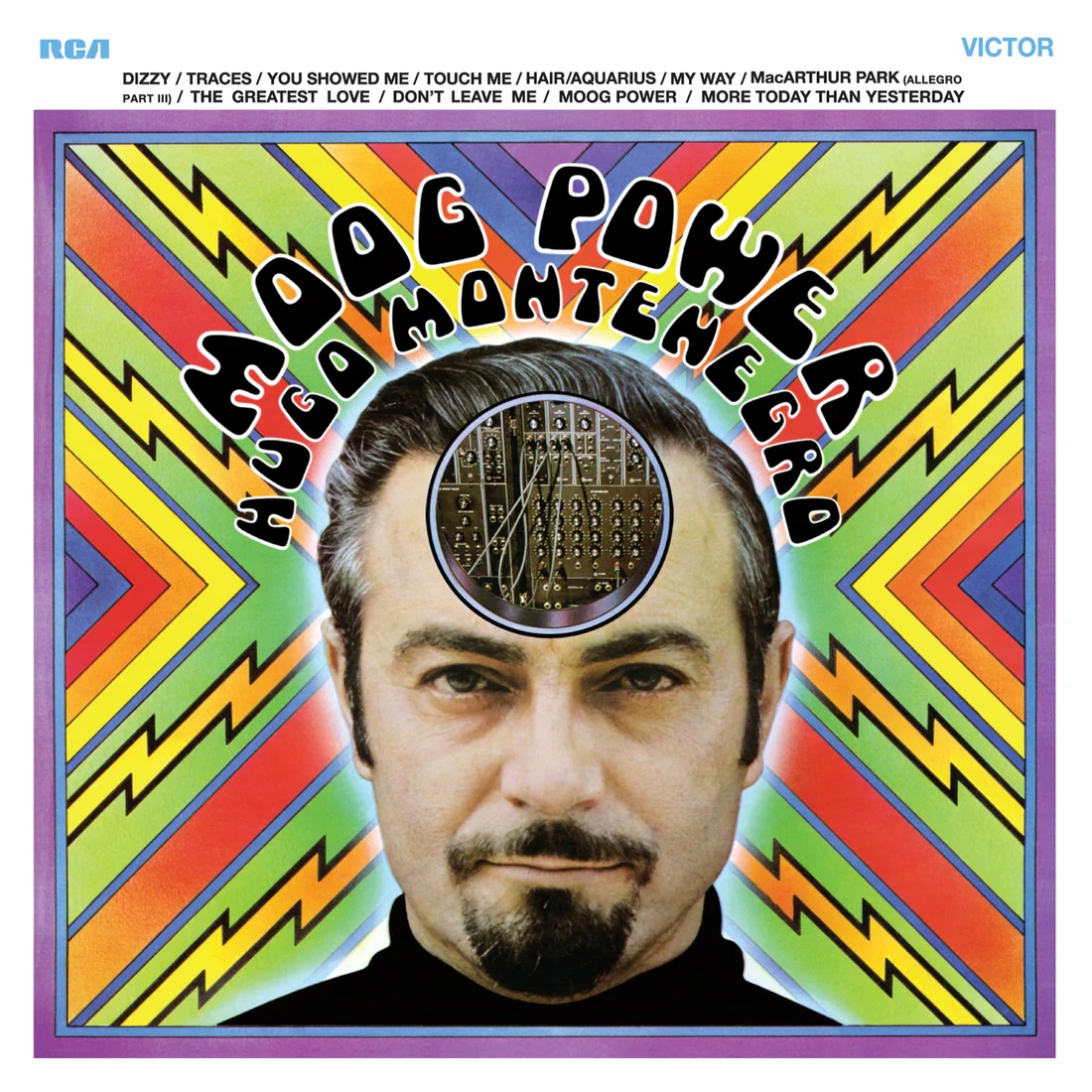

While it is doubtful such days are behind us, Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris 1910-1930 at the Guggenheim provides a welcome respite. Orphism is, if not quite a little remembered, at least a little mentioned movement of art, poetry, and dance that served as a kind of antechamber to the better remembered -isms of its era: Cubism mostly, but also Symbolism, Neo-impressionism, Fauvism, and Futurism.

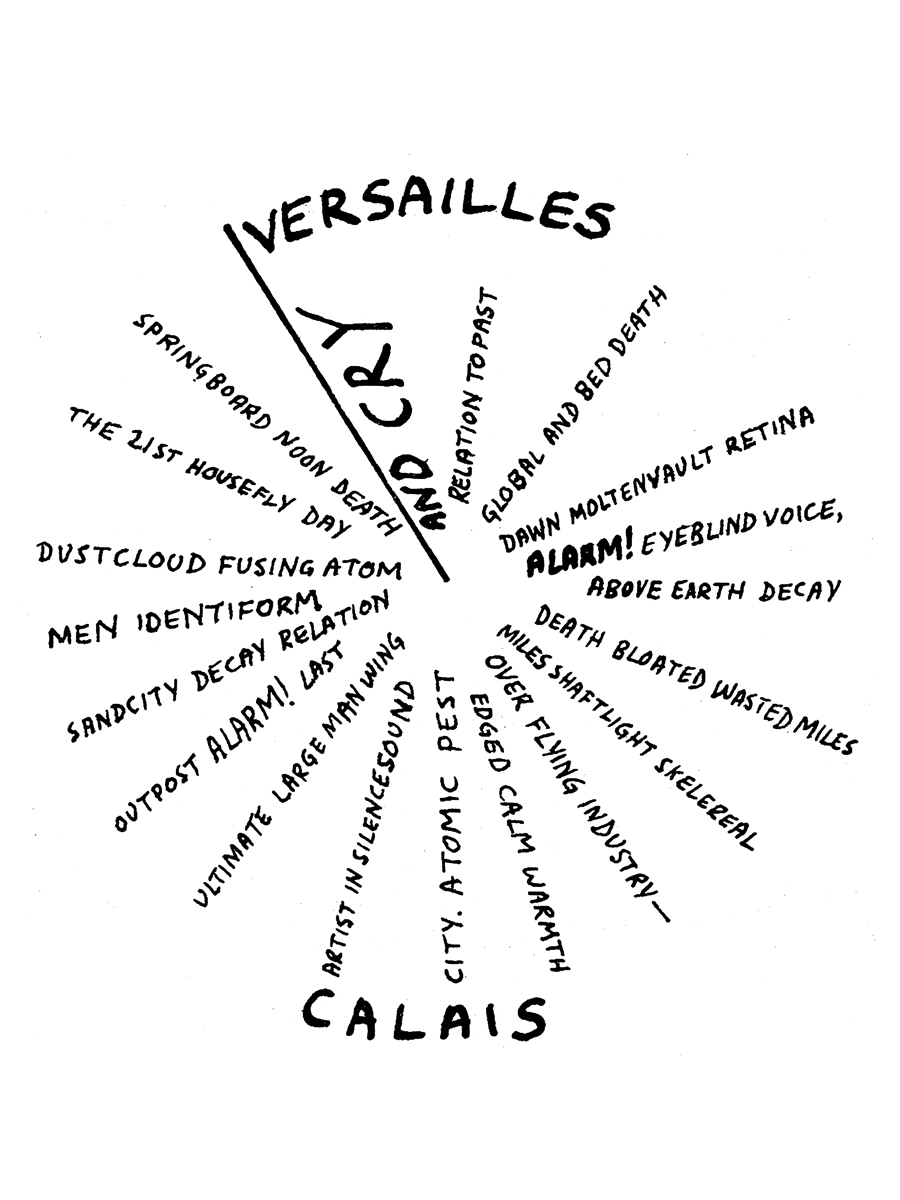

The phrase came from the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who in his 1913 book, Les Peintres Cubistes, Méditations Esthétiques, explained how there wasn’t one Cubism so much as four: Physical Cubism (embodied by the largely forgotten Henri Le Fauconnier) which hadn’t yet broken with 19th Century representation; Instinctive Cubism, in which artists painted not from visual reality but from instinct and which includes artists that are scarcely thought of as Cubists (like Henri Matisse); the Scientific Cubism of Picasso, Braque and Gris, with its geometric forms and analytical approach to space; and Orphic Cubism, which didn’t so much attempt to describe reality as describe what reality feels like. Borrowing its name from the Greek poet and lyrist Orpheus, it was more abstract than the other Cubist tendencies, and more spiritual and interior, more awash in light and color.

The most representative—and maybe the best of the new style—was Robert Delaunay’s First Disk, a 53-inch tondo that was one of the first purely abstract paintings of the 20th Century. Delaunay was born into privilege, the son of a Parisian engineer and bohemian mother who insisted that she was in fact a countess. They divorced when Delaunay was four, and he went to live with an aunt and her husband who saw to his artistic education. At first Delaunay fell in with the Post-Impressionists haunting Paris just after the turn-of-the-century. But after a stint in the sticks as a military librarian, he met Sonia Terk, a Russian-born Jewish artist who at the time was married to a German art dealer (the Countess was a frequent visitor to their gallery, occasionally bringing along Delaunay). Delaunay and Terk eventually became the twin pillars of Orphism, and Robert especially was known as having an almost fanatical devotion to the craft, and for the ability to bore a room with his enthusiasms: “The Delaunays start talking art as soon as they wake up,” Apollinaire once remarked, not entirely kindly.

Theirs was a time, not unlike our own, when the sensation of being alive gave to a sense of everything happening everywhere all at once: electric lights, air travel, the Parisien Metro, to say nothing of the telegraph, the telephone and the radio, the rise of the popular press and the discovery of subatomic, previously unknown particles, which were (apparently) around us all the time.

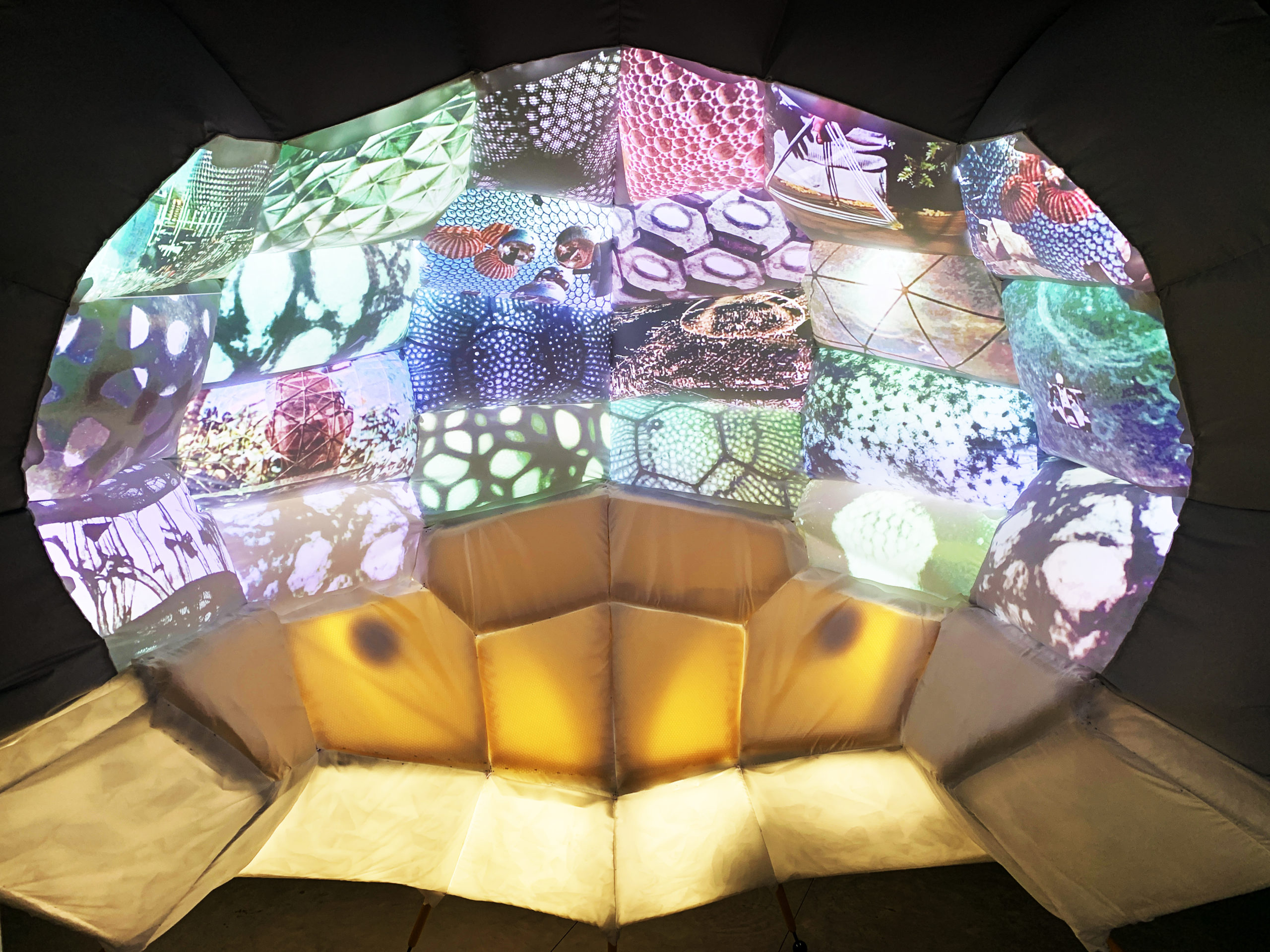

First Disk almost explodes off the wall, a bulls-eye of color and feeling. The painting is divided into fourths, with bands of color narrowing to a point at the center, purple hard up against orange which is hard up against an off-white, while that same purple band is wedged on the outer rim between a blue band and a brown one. It is an effort to explore how we see an object, rather than how to explore what we know of an object. Borrowing ideas from Henri Bergson’s notion of durée, or the continuous flow of time, and intuition, which is how a viewer—or anyone—can experience a multitude of things or sensations at once, the painting explored the notion that the universe is not static but malleable, a shift in perspective changing its makeup. “Delaunay believed that if a simple color really determines its complement, it does so not by breaking up light into its components but by evoking all the colors of the prism at once,” Apollinaire explained in a 1913 lecture. “This tendency can be called orphism.”

Theirs was a time, not unlike our own, when the sensation of being alive gave to a sense of everything happening everywhere all at once: electric lights, air travel, the Parisien Metro, to say nothing of the telegraph, the telephone and the radio, the rise of the popular press and the discovery of subatomic, previously unknown particles, which were (apparently) around us all the time. It was a dizzying, if not disorienting time, and the Delaunays studied the color theories of 19th century scientists like M.E. Chevreul and Charles Henry who theorized that colors shifted when put in relation to other colors, which explains why Orphism is such a delight on the senses, and why Orphists broke with the early Cubists and their washed gray angles. “But they’re painting with cobwebs!” Delaunay declared when he first saw what Picasso and Braque were up to.

%2C%201917.jpg)

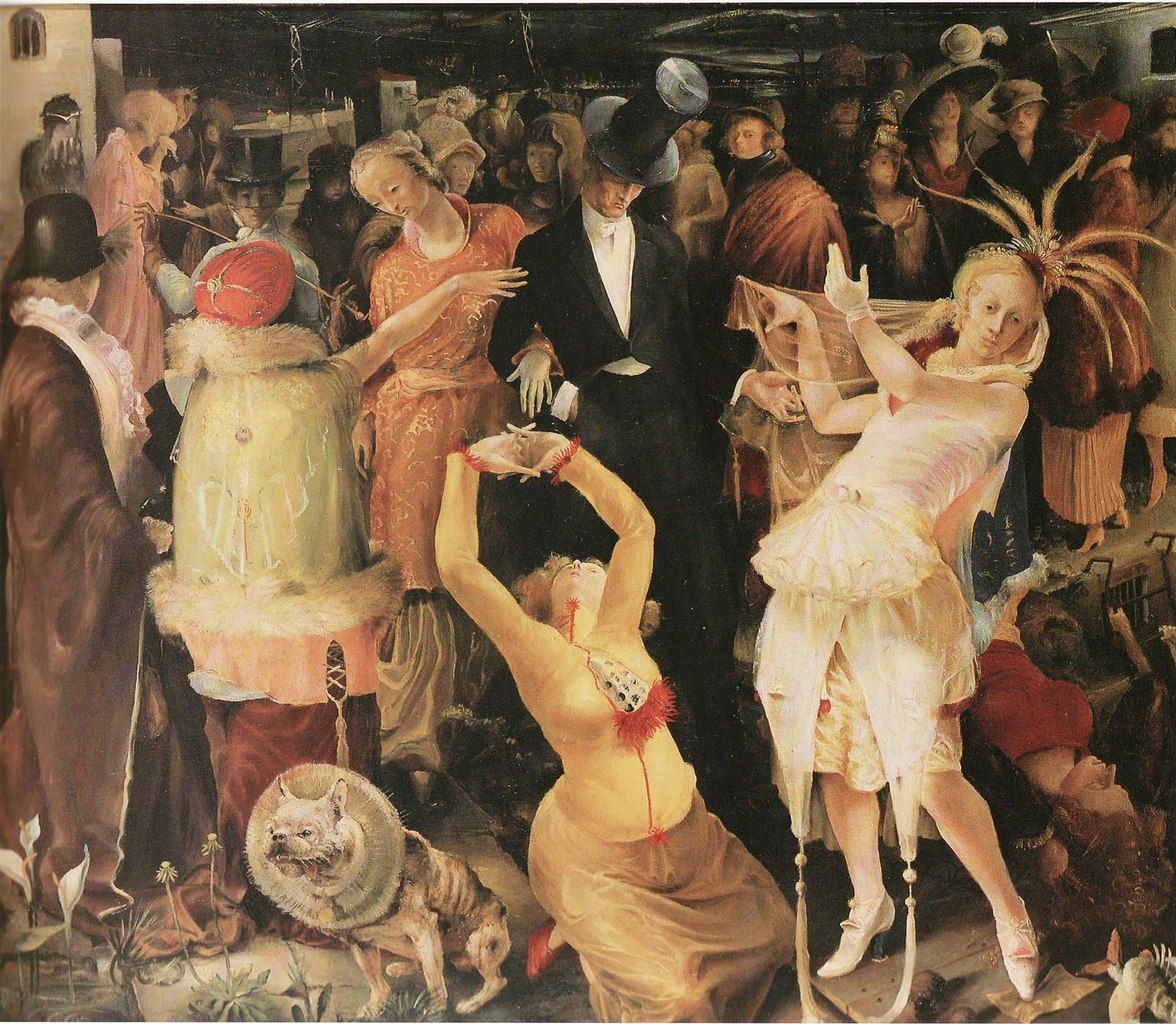

Sonia Delaunay took the approach even further. The principle of all art, she said, was light and what she called the movement of color, by which she meant that through the juxtaposition of opposite sides of the color wheel, a visual effect was created whereby the lighter colors pushed forward and the darker colors receded, thus creating the sensation of movement. It was an idea that could not be contained by the gallery, and so Sonia Delaunay produced clothes, traveling trunks, and book covers in what she called “a free expansion, a conquest of new spaces,” and “the application of the same idea.”

The Delaunays were traveling in Portugal when the Great War broke out, and decided to stay. Orphism was a malleable movement, and by 1914 even Apollinaire had lost interest. One of the many delights of the show at the Guggenheim is how it crams in Orphistic (Orphic?) work from artists whose loyalties were thought to lie elsewhere. Thomas Hart Benton, before he became America’s foremost Regionalist is here with Bubbles, its daubs of pastel paints disappearing into the canvas. Kandinsky’s Improvisation is here too, a painting so wild in its execution that you can almost hear it. (Part of the Orphist project was to create paintings that had the effect of music.) Marc Chagall, perhaps the most syncretic modernist of them all, is here under Delaunay’s sway, his Paris through the Window borrowing liberally from Delaunay, who painted the Eiffel Tower obsessively, convinced as he was that it was the perfect encapsulation of the age. Dadaist Francis Picabia is included, his Physical Culture a swirling mess of form and color, the physicality and rhythm of worker-outers knocking against each other.

This, ultimately, is what makes the show seem so revolutionary, even one hundred years later—maybe especially one hundred years later—at a time when so much gallery and museum space is given to explanation and identity. The Orphists were wrestling with ideas of their age, yes, but this is art that makes the viewer look, and more importantly, makes the viewer feel. It’s breathtaking.

Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910–1930

Ran November 8, 2024 — March 9, 2025

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10128