[drop-cap]

For the last few days, I’ve been downloading leisure music, the lushest and snappiest of songs from 1960s soundtracks: Hugo Montenegro, Keith Mansfield, Piero Umiliani, Lalo Schifrin, Hugo Strasser, Fred Bongusto, Walter Wanderly, Barry Gray and his Orchestra. In expanding my knowledge, I’ve reached another level with this obsession. What I’m hearing now is something about how these figures worked as bandleaders, and what it meant to lead a band, or even an orchestra, as opposed to just being a member of a rock group: the residual guild formation, and the world of familiarized method and training that comes along with it. This is one way that film soundtracks link up with my interest in genre art—with an art of the everyday, the ongoing, the durational as opposed to the punctual.

As much as the late-1960s kids saw this kind of thing as the epitome of “plastic” stasis—the whole experiential plane of their dead-to-the-world parents (comatosed by martinis and Mai Tais in those Xavier Cugat-esque theme lounges)—there still are a few points to be appreciated about this structure from the distance of 50 plus years. First of all, these were jobs. They have a whiff of the union about them, not just in job security, but also in method. There were established ways that tasks were handled by such bands. At the time, this was the antithesis of the new spontaneity that signified the hip, young musician, the countercultural songwriter. But we can also say that every late-60s genius musician, photographed at dusk with prominent sideburns as he walks purposefully with his axe through some rural environment (where the white middle-class kids were moving “back to the land” from the “dangerous” cities), is also a photo of a freelancer. An individual “creative.” The point isn’t just that every atomistic creative is contingent labor. It’s also that that structure totally vaporizes the last vestiges of guild practice, guild knowledge. Those older musicians from the film music bands were like classically trained artists—particularly like Dutch artists from the guilds in the major cities. They had apprenticed with older masters and learned methods; their groups had established musical “solutions.” Many of these were cloying and a little awful. And their ready-to-order character was what irritated the young long-hairs so much. But now they often sound more fascinating than all that earnest back-to-the-land business, in part because they announce themselves as genre music, as just slightly pre-fabricated rather than always straining after that spontaneous authenticity that can now sound so much more dated. The term “number” for song hints at this: “Play that little Italian number with Manfredi and Tomaso on the violins.” Now DJs, working alone in their home studios, go in search of precisely this slightly compose-by-numbers quality when they sample from this older, vintage music.

One of the jobs of these guild musicians was to recompose what was hip at the time and smoothen its edges, turn it into an ambiance.

One of the minor vortices my recent research has turned up, however, is that the interchange between these poles (the authentic long-hair weed smoker and the jaded, whisky-downing guild hack) was even weirder than I had imagined. I was aware that within about five years the sound of swinging London (think Keith Mansfield, “Young Scene”) could be repurposed as calming Muzak in my local Woolworths in upstate New York, where it eased the new parents into accepting their transition from rebel teens and would-be world-changing students to placid household managers, and now, buyers of red plastic storage bins for their 5-year-old daughter’s bedroom. An ungenerous listener might say that this was because a received character was lurking, just under the surface, in the original swinging soundtrack of someone like Mansfield. Doubtful—but in any case, that’s not the point. The point, which causes that opposition above to crumble, is that lots of these soundtrack makers were also parasitizing the big hits by the long hairs: Montenegro has an entire Dylan album (just listen to him getting the church choir to remind mom and dad that the times are a “changin’”—wait, mom and dad are in the choir!). Hugo Strasser does a whole record of American rock (in his Bavarian dance mode); Sinatra (for me, “Sinatra” is only and always Nancy … even if her what’s-his-name dad was occasionally fascinating in films, as when he played a JD in Young at Heart) constantly lifted ditties from the countercultural kids.

One of the jobs of these guild musicians was to recompose what was hip at the time and smoothen its edges, turn it into an ambiance. This meant in some way reintroducing the generic, guild features that the young musicians had heard and hated in the lounge and soundtrack artists and made their music as a protest against. In the long run, perhaps it was this generation of guild musicians who scored the philosophical point (if not always the musical one): music, especially popular music, can’t really escape genre, or not for long anyway. Now Captain Beefheart and Frank Zappa might go farther than most, but even here, there were limits. The idealistic belief that the long-haired musicians had gone beyond generic formulas (in their three-minute folk-inspired FM music pop hits) turns out to age about as well as the ideas of dematerialization of the art object or the anti-aesthetic in art history. The lounge cats grasped this problem, mostly just at the level of their practice: the constant play between insight and system, disruptive spark and familiar ambiance, new riff and routine. This is what’s so entertaining about their quasi-Muzak versions of the folkish protest, experimental, or psychedelic music of the late 1960s. Authentic singularity had become mass-produced system. What these lounge soundtrack musicians were doing was turning the new into a sub-genre, familiarizing us with it.

This practice has a long history, which is more or less coincident with the development of specializations within the history of art: first the Italians get the northern Europeans to paint the landscape backgrounds to their depositions; then some of those specialists begin to create pure landscapes on their own; next others break these landscapes into subgenres focusing on seas, mountains, waterfalls, rivers or even swamps. From there, the process can become even more niche, as audiences get familiarized with narrower and narrower subgenres, smaller domains of visual experience and, in a sense, branding. In the work of a Dutch painter like Salomon von Ruysdael, for instance, this process of familiarizing an audience with a new domain of experience happened within one career: he grasped, after having made some explorational paintings and begun to see a strange, reassuring trajectory in one line of his work, that his calling in life was to paint not just river scenes, but ones with ferries in the foreground organized parallel to the bottom frame of the painting and set off in contrast with boats moving on the diagonal farther downstream. These paintings became a kind of brand. The difference with 1960s music was that it was not the originator but instead someone else who came along and noticed how reassuring and familiar a certain innovation could be—if it was stripped of its rough edges, combed, sprayed with makeup and thus turned into a genre. Once it had been reconstituted by the band leader, one could now hear those faintly saccharine elements even in the original song. First Dylan, then Montenegro, then Dylan overlaid with Montenegro. Now one was always aware of that second, air-brushed tambourine man, in his slightly better-equipped studio.

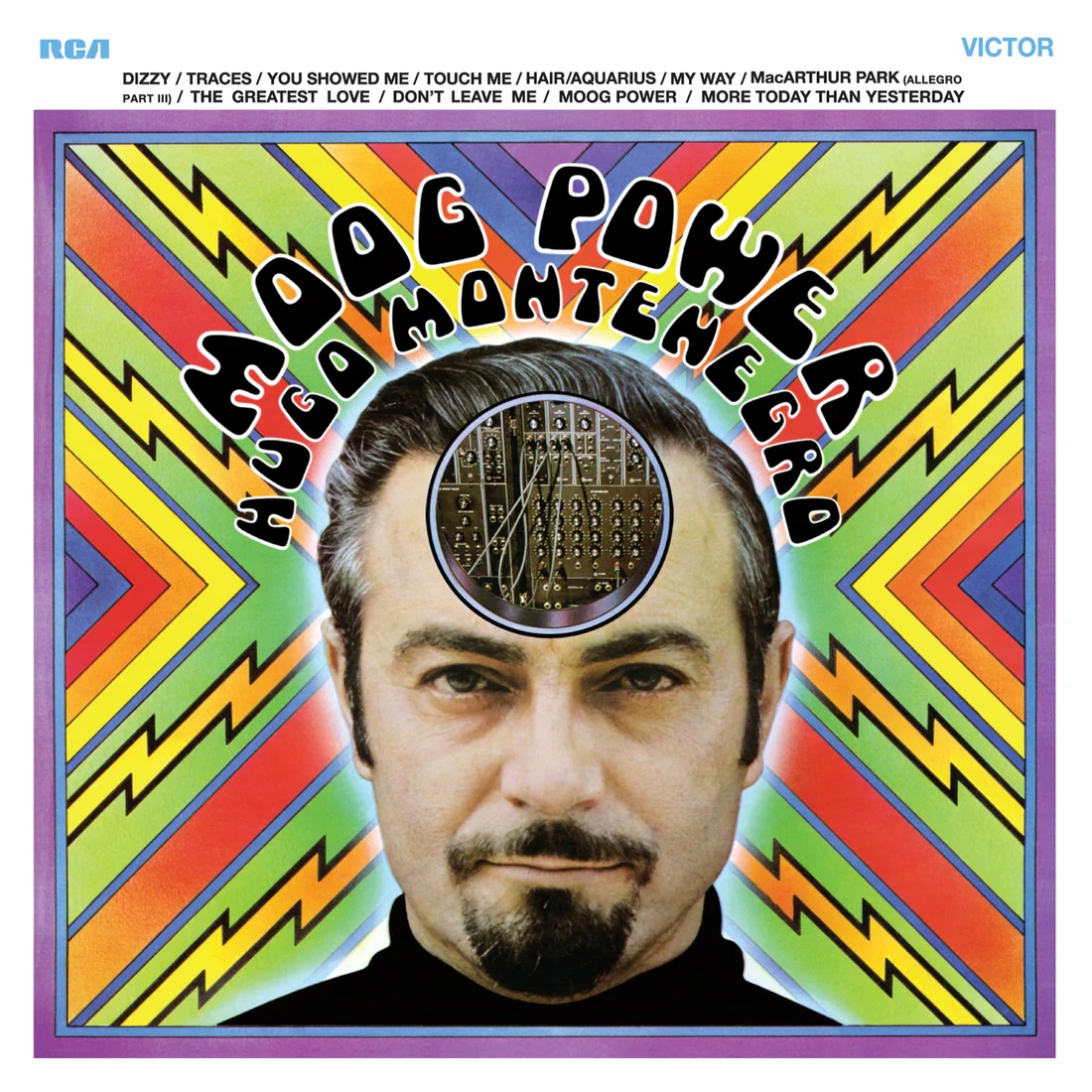

Given this very dynamic, it’s quite lovely and baffling that one of Montenegro’s compilation albums is titled This is Hugo Montenegro, since all his work is about stealing and refashioning other people’s music. The “this” thus points to … what? This process of repurposing? This situation in which Montenegro is a placeholder for the synthetic reassembly of Dylan, the Beatles, Ennio Morricone, The Beach Boys, all the big musicians’ main songs? This bottomless this is apparently Hugo Montenegro. This displaced This. When Montenegro makes Moog Power (1969), an entire LP based on the Moog synthesizer, it’s particularly appropriate: Montenegro is, himself, a high-end synthesizer. This audiophilic dimension to his work perhaps points to another sense of “this” in This is Hugo Montenegro: his ability to monumentalize, in a double-album demonstrating extremely high production values, his totally ephemeral and derived music. This last this would thus point to the economic infrastructure in which Montenegro circulates: the Hollywood studio system, overlapping to a degree with the music industry, that requires a human synthesizer like Montenegro, a captain of high fidelity, even if that fidelity is always to someone else’s music. This last this enables the implausible fact that there could now be, in your hands, a big physical embodiment of a musical career, a double album, composed entirely of catchy, studio versions of other people’s hits. This is the shifty shifter that prefaces our relation to Montenegro in This is Hugo Montenegro. Filling it with all of the above, while emptying this this of nearly everything we have hitherto associated with musical value, Montenegro emerges as a giant of 1960s conceptual art, so long as that last can be understood as a musical genre art.

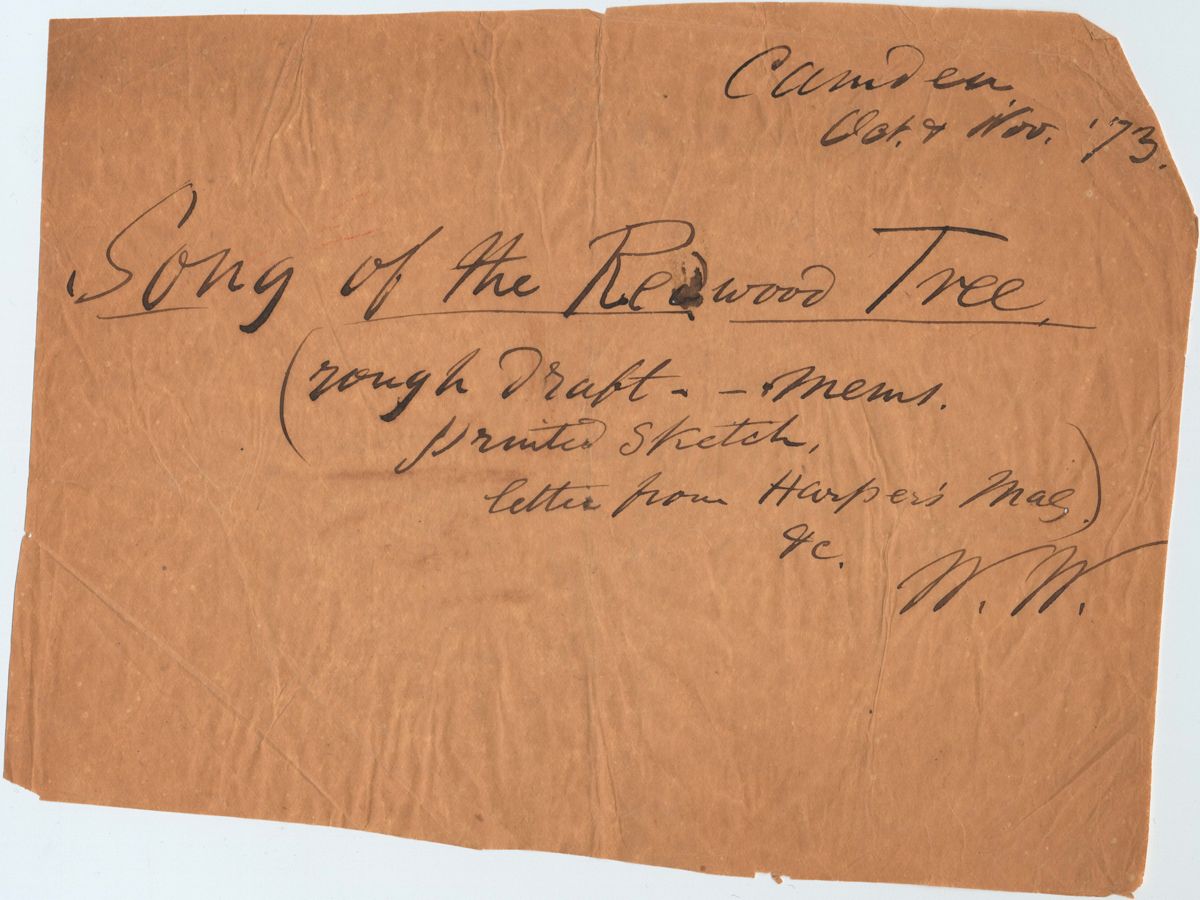

In a way this whole dynamic is sort of like my generation’s relation to Language writing: I’m thinking not primarily of the better-known later manifestations like Flarf and Conceptual writing, but of the writing scene that emerged in San Francisco and Berkeley from about 1995 to 1998, which included Pam Lu, Renee Gladman, Alex Cory, Adam DeGraff, David Larsen, myself and many others. Faced with the Language writers’ earnest desire to destroy genre with the hope of returning us to a primary encounter with words and phrases that had escaped their guardrails, we met this wide-eyed plea for the ritual extermination of our familiarizing frames with the calmness of our inner-Bond villains: “Not until we’ve had a drink.” A generic response, to be sure. But there was, shared in this group, a fascination with genre—with courting it just enough to exert mild pressure on the statement. Not all the way into becoming anything close to a mainstream novelist, but enough to imagine the experimental novel less as a collection of sentences that force one to begin at zero each time than as a story whose shifting frame is an important character. Still, the choice wasn’t simply between purity and genre, since after two decades of disjunctive poetry, further work in that vein sounded to us like generic avant-garde poetry, work that signaled its fitting in with its first gap or ellipsis, its reassuring continuity with the parents precisely by its lack of continuous syntax. Putting pressure on genre was thus also a way of escaping this more familiar genre that awaited poetry that continued seamlessly in the disjunctive tradition.

But we were talking about band leaders. Flip that Francesco De Masi LP and I’ll see if I can remember where I was. Oh yeah—the lounge captains: you have to love them because they’re all interpreters. Not just creators. Interpreters of popular songs, as I’ve just said about Montenegro; but also, more fundamentally, of films. This is like a form of criticism. It’s a commentary. It doesn’t involve making things up from scratch. It begins with coordinates, presuppositions, concrete problems. Now, how you get from there to Morricone’s “Il Grand Silenzio”; Lavagnino’s “Gli Specialisti” or Piccioni’s “Capriccio”—that jump does involve some genius. But it’s situated genius. They wake up each day with “materials” in front of them that it’s their job to process into a series of sounds. These materials are filmic narratives, often low-grade ones. When they do their job well, their interpretations become part of the original materials, seemingly inextricable, though always added after the fact—as is the case with the best poetry criticism too. We can watch a scene from a Spaghetti Western, even one with an amazingly catchy soundtrack, and still insist for whatever reason on temporarily shutting our ears to Morricone’s incredible sounds. Something can come of this, as can reading Wordsworth without thinking of Geoffrey Hartman or Paul de Man. Other paths are open, can be made; the link can be suspended. But what all this tells us is that the soundtracks, like the critical commentaries I most admire, have effectively overcoded the original films or poems, have become part of their landscape. We know at some level that the two are independent, and can insist on this when needed. But our inclination will be to appreciate the link, because it makes the original even better, it draws out of it some powerful latency, releasing it into the atmosphere, making it more available to experience. Perhaps the difference between film soundtracks and poetry criticism is that many of the filmic narratives—say those from the 1960s—are ultimately less interesting than the music to which they gave rise, whereas the best poems are not at risk of dropping away in some gradual shift of interest toward the commentaries.

Film music is often dismissed as thin and derivative. We imagine that this is because the music is literally derived in relation to, and as a response to, the films. But maybe the films are only temporary scaffoldings, heuristic points of departure for the ultimately more important music? Maybe the film’s purpose was really to generate some songs by Morricone or Piccioni, which live into the present in ways unavailable to pretty much all the movies they scored. Of course, what’s also imagined to be derivative about the film scores is that they are generic; they use short-hands and formulas. Clement Greenberg would call them kitsch.

But maybe these formulas are what now recommend the music most of all. I tend to gravitate to musicians that are just a tiny bit compromised, like Lee Hazlewood—not too pure. Not just in his persona but in his music. Not just composers, but arrangers. Or take Hugo Montenegro again. Let’s visit him now while he’s recording “Aces High.” At first, with the camera pulled in close, we just see the drummer and the bassist in their intense opening. We assume we’re in a tight little 3 or 4-piece band. Then at 17 seconds we get a wider angle shot of the room and see Hugo (brown pant-suit, cigarette, closely cropped Satan mustache) turn and conduct the singers and then the orchestra members who’ve just joined in. He first points decisively to the chorus, then a partial turn and, now with his right hand, index finger out, he signals the violinists. He’s in the RCA studio. There’s a lot of new, sparkling equipment. This is after his move from New York to Los Angeles. Now we see him motioning to keep the tempo. Perhaps the Irish conceptual artist Gerard Byrne is making the film; it could be a bit like his In Our Time (2017), which recreates the studio of an analog radio DJ and shares his real-time broadcasting, a world of the continuous now that couldn’t be more “then.” Only the film soundtrack orchestra leader’s world isn’t just about producing continual nowness in that way, live; it’s about recording it, inventing it—by listening to what “the kids” are making in their music, and by using this to dream up new soundtracks for Hollywood. Everyday, these composers work with the films on in the background—perhaps while they assemble their period diet lunches of cottage cheese in iceberg lettuce cups, or puff along (headbands, tight-fitting sweatsuits) on old-style stationary bicycles that loudly fan their living rooms.

But we were talking about what was lost when the band leaders vanished. Put on that Fred Bongusto LP, over there by the window, and I’ll try to be fair to the DJs who replaced them. It’s not surprising that many musicians understand this transformation from the band leader to the DJ as a progressive development. Certainly it allows more people access to complex music making. In this sense it’s democratic. And when it’s good, which it often is, we get the likes of Alex Gimeno (mastermind of Ursula 1000), perhaps the best dance electronica conceptual artist of all time. But before we rush to the universal common sense about how the digital age has, once again, improved our lives, pause for a moment. Because there’s more to be said about this transformation: what we also get now, with the autonomous home producing DJ, is a world in which the bass track, the vocals, or the violin, never comes with an attitude or an orientation that needs to be negotiated, needs to be developed in exchange with an actual human being. Again, often great. But with the complete disappearance of intersubjective exchange there’s also a loss. It’s not just that, in the environment of the old band or orchestra, one of the musicians might disagree or propose a change, though certainly that happened. It’s that each of these older players would have learned from his guild how to solve certain musical problems, or simply find a role in an ensemble—structuring harmonies, developing melodic riffs, adding tone to a larger composition. These techniques could be smoothed or pushed in this or that direction. But in a sense the conductor of an orchestra—the band leader—was always up against some engrained method. We hear the residue of this in the recordings of this whole generation of 1960s lounge captains and film soundtrack composers. Perhaps this is what gives the larger terrain of sounds its great period character. DJs are in this sense different from conductors. While the DJ is also, obviously, an attractive figure—the home composer who can make (or find) all the sounds he wants himself—today I pine for the old world of the 1960s film soundtrack artist and band conductor. He has conversations with bandmembers about how they do their parts; he negotiates, suggests, and with hand gestures or a baton, indicates volume, rhythm, crescendos and diminuendos. And he composes collectively. It seems very likely that I’ve missed a calling, and the historical window for its realization.

When the credits ultimately appear, my fascination with lounge musicians, bandleaders, film score composers is more than just in the music they made—though it begins there and never leaves it entirely. As figures of vanishing guild production, they are also genre artists. Genre may appear to be the opposite of the avant-garde, but this is an illusion. Still, these figures tickle the keys of their Hammond organs and croon to me from the other side of a massive technological and social divide: Band, bandleader, soundtrack, soundtrack artist, recording, home recording—all these terms have undergone basic seismic disruptions since the 1960s. As we moved away from analog, their translations defied neat analogies. And as we moved equally into privatization, the social nature of existence and production as a musician also changed equally. This turns listening to 1960s bandleaders into historical research, research into an alien time, with its alien artifacts. It means that mobilizing them as figures for poetics runs up against limitations, since thinking of a writing practice in related terms will now, given how music is made and organized, tend to land us closer to the DJ than to the bandleader.

The DJ also has a more positive and even philosophical place in my thought. This is where a figure like Alex Gimeno becomes a model: he is a historiographic musician, not simply in the sense that he’s well informed or curious about music’s past. No, in a more interesting way, he goes back into the past to invent other futures. And in a sense to change the past. Actually achieving such an effect, as he does routinely, is extremely rare in the larger world of DJing; but when it happens, music has the advantage of presenting sounds, even sonic textures and modes of production, that existed objectively in the past (they are recognizable as such) but are no longer constrained by the limited or oppressive thinking of their older moment. He is able to do this, perhaps, in part because he doesn’t have to negotiate with actual musicians, much. He can turn up the latencies when they emerge quietly in the past, and edit out that other part, later on, where they get overburdened by bad drama or overly familiar pathos or riffs we can’t hear anymore. He can engineer a past we never quite had as a future we are always eager to step into.

Perhaps this is more difficult in writing. But, like the bandleader, my daily work involves responding to givens, which can be formal constraints, sites, art objects, buildings, songs. Still, lacking the guild knowledge myself, I can only speculate on this world of yore. Unless of course it is an inescapable self-image distortion to imagine that one is not a guild member, not a genre artist. Maybe, in retrospect, the formation I received in architecture school, in punk bands, in experimental poetry, and in the artworld will have done just that for me. Difficult to say.