I first published Dave Thomas’s Mexico City World Map fifty-two years ago in my fledgling literary and graphic arts magazine Montana Gothic. That was in 1974, just after I had returned to my hometown of Missoula from a short expedition to Paris and a two-year stint working at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. I returned to start Black Stone Press, a small art and literary printing and publishing business. Under the Black Stone Press imprint we published Dave’s work in all six issues of Montana Gothic. Dave and I already had a history going back to our undergraduate days together in 1968. I was the Missoula home-boy who befriended the artistic country boys and their female counterparts as they trickled into Missoula from the Hi-Line, leaving behind their small towns to receive a university education. They came from the Blackfeet and Flathead Reservations and from towns like Ronan, Choteau, Plentywood, Chinook, and Ft. Belknap to drink at Eddie’s Club, write poems, and travel beyond their native range.

Dave came down from Chinook and enrolled as a student of political and military science. Becoming exposed to the more philosophically inclined professors, he added humanities studies, and, after graduating in 1969, began a lifetime devoted to labor and literature, moving from construction job to construction job, and traveling in between when work was slow. He worked building the Libby Dam on the Kutenai River, gandy dancing on the Northern Pacific Railroad, and numerous jobs at building sites all over Western Montana. He was the Zen wanderer, the Taoist poet, the Beat road-master. His literary forebears were Gary Snyder, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Han Shan, with a dash of Philip Whalen. Dave’s wanderings often brought him to San Francisco, where we continued our friendship whenever I was in the city.

Four years after establishing Black Stone Press I pulled up roots and left Montana for the final time in 1978. I returned home from California as often as I could in the years immediately following, usually arriving at night after two long days of driving across the Nevada desert and north up Highway 93 through Ketchum to Missoula. Inevitably, my first stop would be Eddie’s Club and without fail I would find Dave sitting exactly where I saw him last, perched at the west-end of the bar beside the telephone where he watched it all play out…

beneath the pressed tin

ceiling

while seated

at the bar

a longhaired kid

a refugee

from Montana’s desolate

Hi-Line

studied the bottles aligned

below the mirror

beginning to reveal

the crowd growing

out of the night.

Faces gnarled with angst

etched by the Great

Depression

World War Two

gave way to shining eyes

and wide grins

as the psychedelic kids

swarmed the bar

defiant of authority

and the war in Vietnam

—from “Legendary Glimpses in Eddies Club”

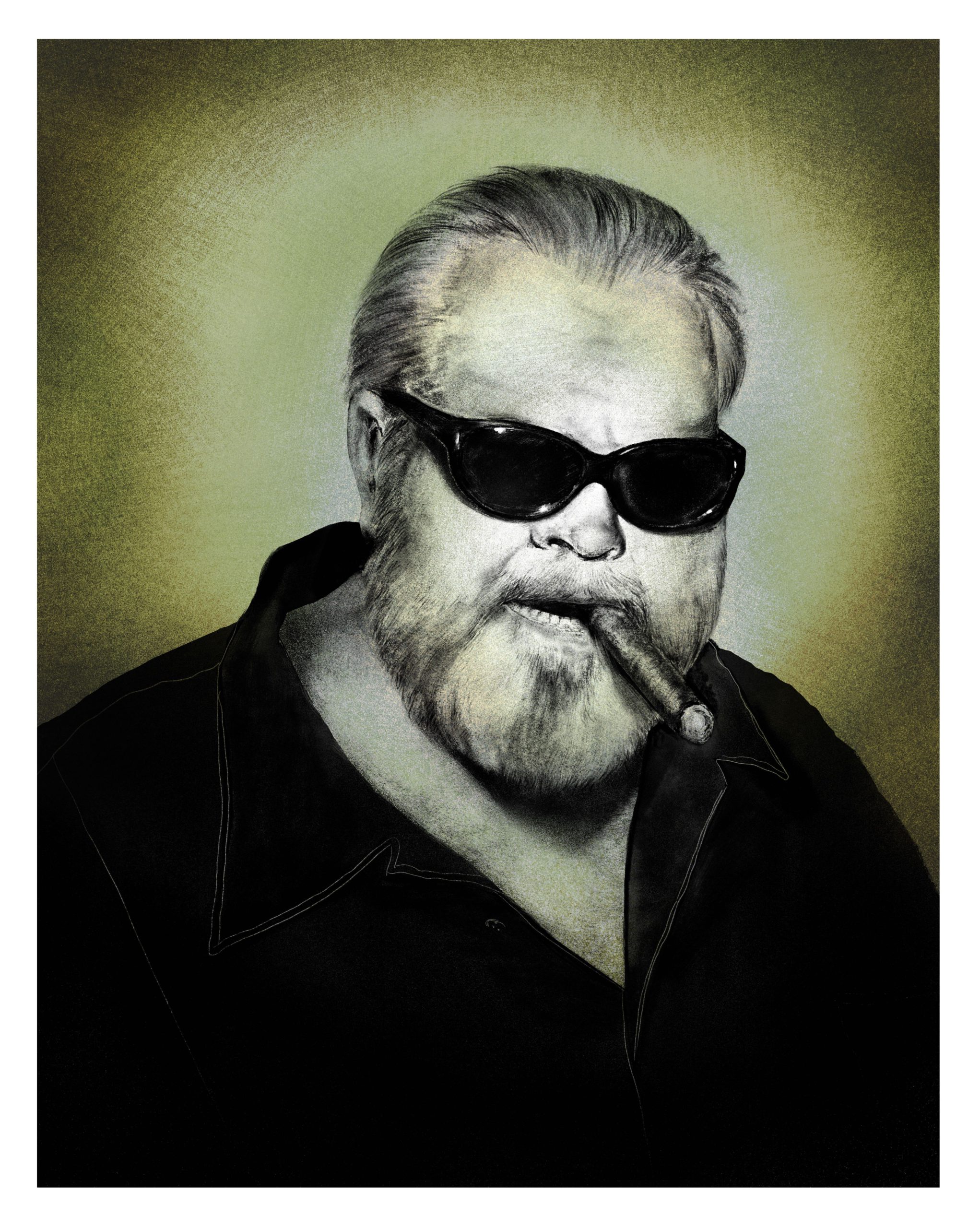

Dave is a familiar figure in Missoula with his long white beard and sturdy White’s work boots crossing and re-crossing the Higgins Bridge over the Clark’s Fork River on his daily rounds back and forth to the Montagne Apartments at the corner of Third and Higgins, where he has lived for over forty years in a small room with a sink, hotplate, and bath down the hall.

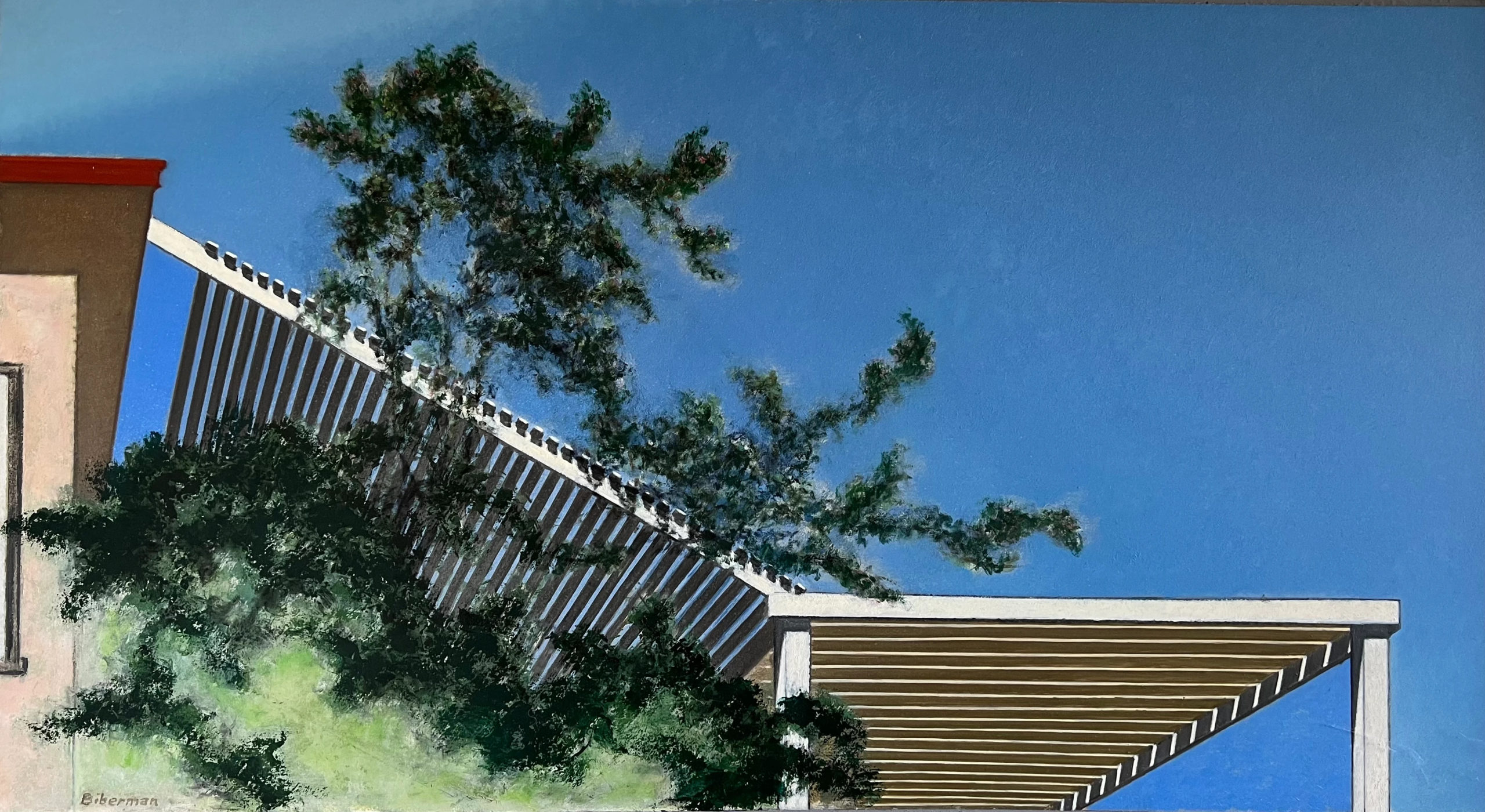

Following Dave’s appearance in the first Montana Gothic, I designed two slim volumes of his poetry for other publishers, Fossil Fuel and Buck’s Last Wreck, and later, published three poems under my Hormone Derange Editions imprint. They appeared in a portfolio that included sixteen illustrated broadsides by poets and writers from either California or Montana: Robert Bringhurst, Victor Charlo, Barry Gifford, Greg Keeler, William Kittredge, Ed Lahey, Milo Miles, Rick Newby, Paul Piper, Thomas Sanchez, David E. Thomas, Philip Whalen, and John Yau (from Massachusetts). In 2024, looking for a new project, we selected seven poems from Thomas’s previously published books and began composing Eddie’s Club in our newly acquired Monotype Dante typeface. The frontispiece, a wood engraving by Keith Cranmer, depicts the tattered neon sign that once hung above the entrance of Eddie’s Club, the north-end bar (now Charlie B’s) where the artists, writers, broke-down cowboys, railroad workers, and Missoula bohemians hung out in the 1960s—and still do as far as I can tell.

Nearing the end of the production process, saloonista Susan Filter, recalling the bar-crawl origins of the now infamous Venice carnivale revival in the 1970s, suggested we all travel to Missoula to celebrate the publication of Eddie’s Club with a bar-crawl of our own through some of Dave’s familiar haunts. We printed a flyer to be posted around the downtown bars and bookstores.

The cover reproduces a detail from the famous 1870 Walter W. De Lacy Map of the Territory of Montana with portions of the Adjoining Territories. It depicts the original “Reserve for the Flathead Indian Tribe” in the Bitterroot Valley. Nineteen years later, Chief Charlot signed General Carrington's treaty agreement, and the Salish were forced to accept removal to the Flathead Valley, making the painful decision to give up their homeland in order to preserve their people and culture. They left the Bitterroot on October 15, 1891.

After we finished the binding, Saloon members and their friends from Berkeley, New York, London, Kathmandu, and Birmingham, Alabama flew to Missoula. The plan was to visit four bars, ending up at Charlie B’s (formerly Eddie’s Club) where Dave read “Legendary Glimpses in Eddie’s Club” celebrating (and memorializing) his friendship with Missoula fiction writers Chuck Kinder, Jim Crumley, Max Crawford and their barfly cast of characters. The first two bars on our trail were crowded—and loud—that Sunday, but the Union Club had no band that night and Dave took to the stage. At Charlie’s, surrounded by Lee Nye’s portraits of the now legendary Club barflies and broke-down cowboys, the whole crowd fell silent as he read:

the Hi-Line kid

sitting at the bar

kept his stare

at the mirror

and watched it all

play out

year after year

as the light

shifted

from particle

to wave

and the silhouettes

faded to dust

on a breeze.

The reading was deemed a great success, a third of the edition sold in less than four hours, and we headed out for dinner.