[drop-cap]

It was raining when we emerged from the Metro and walked to the Holiday Inn on Rue de Lyon. With less than 24 hours before our train left Paris for Marseille, we dropped our backpacks and returned to the streets. A death in my girlfriend's family had brought us here. It was June, summer, and none of us had prepared for cold weather. We shivered in front of a half-burnt Notre Dame and a deserted Eiffel Tower.

The next morning we had time to visit the Musée de l'Orangerie. On our way I felt the gaze of Parisians looking us up and down. After more than a year of lockdowns, France had just opened up to travelers with a negative covid test and proof of vaccination. The pandemic had brought anguish but it had also rinsed the city of tourists. I imagined that everyone who saw the seven of us, like the scowling baker at the boulangerie in Bastille, was remembering how to be offended by our presence. Lockdown had left them rusty.

I’d once thought of Claude Monet’s Water Lilies as the McDonald’s of the art world, up there with the Warhols and the Magrittes that you could find round the corner in any oofy art museum. When we entered the Orangerie, a Mecca for Monet devotees, I kept my feelings to myself. Built in 1852 to keep the orange trees of the Tuileries Palace warm in winter, this neoclassical greenhouse has shown eight large Water Lily murals–known as the Nymphéas–since 1927, the year after Monet’s death. On permanent display in two adjoining oval rooms, the paintings live, it has been said, in an architectural symbol of infinity.

Like the private pond that inspired all of the works in his “Grand Decoration,” Monet wanted the Orangerie to be a sanctuary for the people of Paris, a place where, in his words, “those with nerves exhausted by work would relax.” Other wall texts repeated Monet’s desire, and by the time I sat in front of Two Willows (a 55-foot panel in the first room), having been told, in three translations, to relax, I could not. Perhaps I was distracted by small things, like a mutating virus, or the latest episode of war in Palestine. But soon enough I succumbed to the lavender waters of this “flowering aquarium” where light is God and lilies look like “melting ice creams,” as Kenneth Clark once said.

Instead of reducing the authority of the originals, millions of reproductions have been traveling the world like envoys, taking up space, and meeting me on mugs and clocks to advertise the supremacy of French art and “Frenchness” in general: Liberté, Egalité, Water Lily?

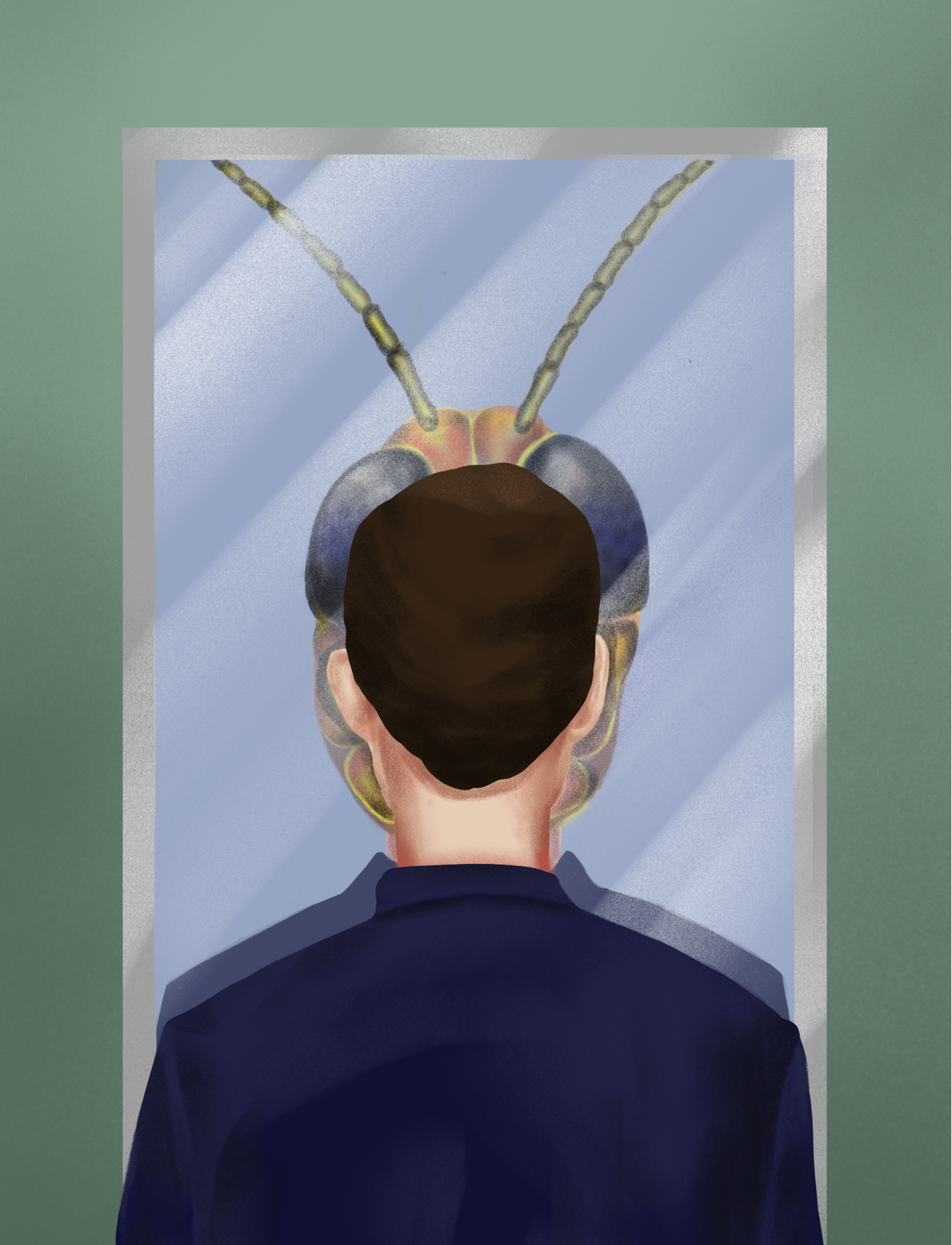

Clark was talking about Monet’s impressions of the Rouen cathedral, the way his thick brushstrokes dissolved each facade into vibrating puddles of cream. I saw the same effect in Two Willows, the “lilies” melting across a multi-dimensional universe of strawberry sundaes. Of course, I’d seen them a thousand times before—on mugs, postcards, t-shirts, chocolate boxes, puzzles, umbrellas, dildos, and diaries, not to mention the hyperreal sea of the Internet (and yes, there are NFTs). There in the Orangerie, my mind oversaturated with the history of these reproductions, the real thing felt like another copy. Monet’s innovations in form and perspective were frozen in old time. All I saw in Two Willows was a design for a phone case.

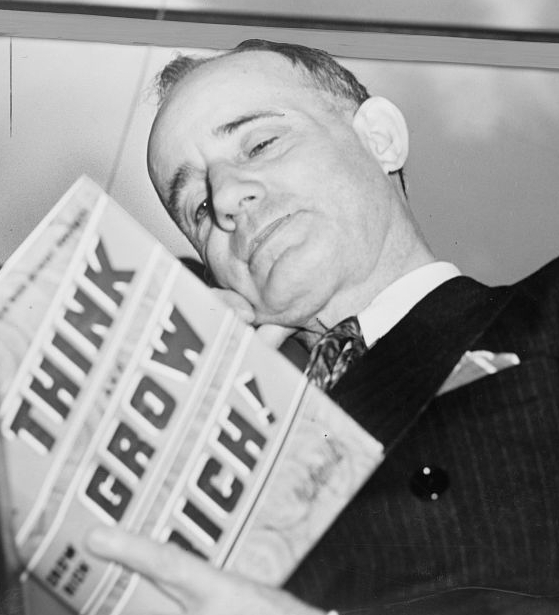

In 1972 John Berger, borrowing from Walter Benjamin, warned that modern ways of reproducing art were lessening the actual artwork’s authority. With so many copies appearing in books and other media, he said, “images of art ha[d] become ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free. They surround us,” he continued, “in the same way as a language surrounds us. They have entered the mainstream of life over which they no longer, in themselves, have power.” Berger was worried, maybe even paranoid. Once safe and protected in the museum, the empire of art was suddenly being set free by copies of itself. Scary!

Fifty years on, in a world dictated by currents and currencies of images, I’m convinced the opposite is true: The real works of the Nymphéas—just like the original Campbell’s Soup Cans in the Museum of Modern Art and The Scream in the National Gallery—have never been more powerful. Instead of reducing the authority of the originals, millions of reproductions have been traveling the world like envoys, taking up space, and meeting me on mugs and clocks to advertise the supremacy of French art and “Frenchness” in general: Liberté, Egalité, Water Lily?

“Did you see the Magrittes downstairs?” my girlfriend asked when she and her family found me in the ultramarine waters of Clear Morning with Willows, which I had been staring at, hopelessly, for fifteen minutes to see if it “acknowledge[d],” à la Marienne Moore, “the spiritual forces which... made it.” In a final attempt to enter what Theodor W. Adorno described as the artwork’s “autonomous realm,” I stood as far away as possible. Camille Pissarro once decided that the best distance to view an Impressionist painting was three times the diagonal of the canvas. If Monet hadn’t been so ambitious—Clear Morning with Willows is 42 feet long—I might have found God.

Instead, it became obvious that we needed to leave the gallery. Lunch was imperative, and the train to Marseille could not be missed. “But Magritte!” I said as I ran downstairs on the back of a promise that I would spend no more than five minutes in “Renoir/Magritte: Surrealism in Full Sunlight.” After reading the introductory wall text at a jog I proceeded to stop only momentarily in front of select paintings, like the reclining nude of The Harvest, whose colorful limbs and breasts looked more like the sleeves of a jester’s hat than the original Renoir.

By the time I made it to the last wall, my promise broken and my mind filled with more nudes than I bargained for, I had discovered a new side of Magritte, far removed from the faceless men and floating apples I studied in school. Robert Hughes once described this side as the “low point” of Magritte’s career, characterized by “impressionist fuzz and expressionist slather,” but I found a warmer take in the catalog. “In 1940, in a departure from his unusual and unsettling Surrealist style,” wrote Cécile Debray, Director of the Orangerie, “Magritte turned his attention to Renoir, ‘the painter of happiness,’ to banish the horrors and chaos of World War II and his experience of exile.”

Monet had reacted similarly to the First World War, only he had turned to his pond and its reservoir of light for solace. The final panels of those years lived upstairs, in the oval rooms, which Monet had, in a gust of patriotism, donated to France to celebrate the Armistice. As Ross King reveals in Mad Enchantment (2016), a fascinating book that charts the turbulent life of the Water Lily murals from beginning to end, Monet shared his wishes with Georges Clemenceau in 1918: “I am on the verge of finishing two decorative paintings,” he wrote in a letter, “that I want to sign on the day of Victory and have you offer to the State on my behalf.” He would call the panels his “war work.”

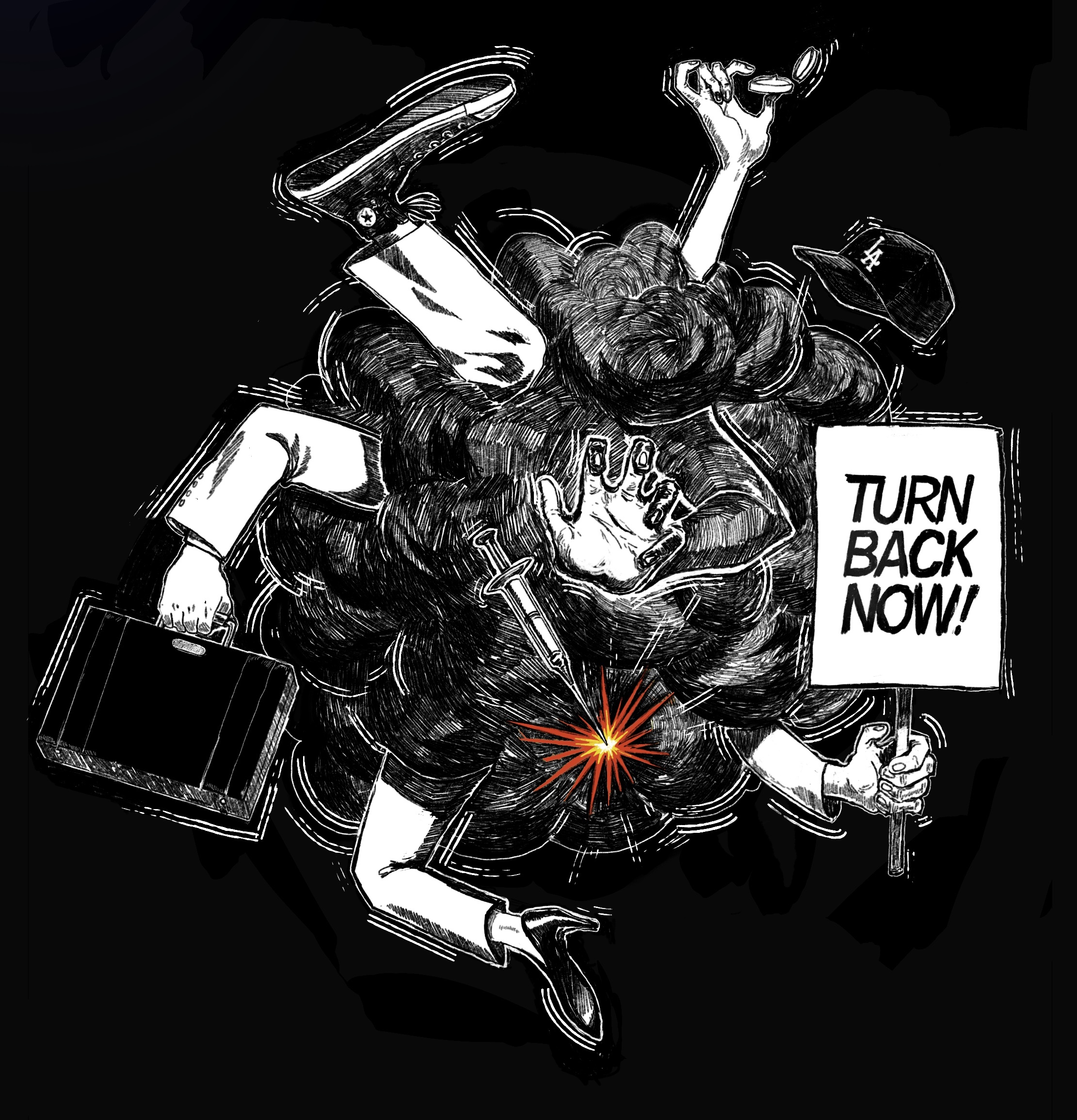

But Monet would give them no Freedom of Mind, as Magritte did in his painting of that name–a pensive, topless woman holding a pipe. Nor were there any angelic, winged penises floating among the lily pads, which Magritte drew for Georges Bataille’s Madame Edward and which I saw moments before returning to the family—tired, giddy, and dazzled by French verve: In what political universe, fashioned out of today’s magnificent mess, could an American curator hang such lovely things?