[drop-cap]

Fires were burning in every state and territory and some local groups in Perth had organized a vigil. A few minutes late, my partner and I ran from the parking lot to the yellow steps of the Cultural Centre where about 400 people had gathered in a circle. We joined them. Appeared casual. Saluted the hot afternoon with fresh beads of sad sweat.

The Cultural Centre is a plaza five minutes from downtown Perth. It is named for its predicament: move ten feet in any direction and you risk being asked to think. North, the concrete bastion of the State Library of Western Australia. Opposite, the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts shows off with a beer garden in a red building older than Federated Australia. The theater is east. West, the newly renovated museum. Further west, Charles Sierakowski’s Brutalist bonanza built in 1979 to house the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Should you wish to flee, the train station is south.

When people hold events in the Cultural Centre, they do so not for Barthes or Basquiat, but for the yellow steps, which function as a kind of public amphitheater. In front of the steps is a giant television monitor. High up on stilts, perfectly erect, it brings people down even on days when nothing is happening. By the time we took our seats the vigil was a go. People were clapping. So I put my hands together too, desperate for clues. A man approached the microphone. Flames were burning on the screen behind.

“We’re gonna hold a vigil together,” he said, “to come together in spirit.”

If flip-flops and shorts were a tone of voice, this man sounded like summer. Inviting us to mourn fires that had already burned 25 million acres and killed 27 people and more than a billion animals, he could have been a swimming teacher talking about next week’s lesson. Then, perhaps self-conscious of past wrongs, he pleaded, “We’re not here to lecture you.”

In the center of the plaza, a few feet from where he was talking, Aboriginal elders sat together, their faces firm and downturned. Before them two pails of smoldering leaves lent wisps of smoke through the air, white and light as steam. Perth sits on Noongar land, and the leaves would have been set alight during the Welcome to Country ceremony we’d missed as latecomers. Extending around the speakers was the wooly circle of mourners, the Green Left, momentarily on leave from saving the planet. And, I suspected, intensely pessimistic about the beer garden next door, where someone had begun laughing their way into a kind of choking shriek. In retaliation the circle cheered for the next speaker, a stocky, gruff volunteer firefighter named Ben. As he told us about himself—he was 18 years old and had been fighting fires for the past four—a baby, on the run from her father, began to waddle up and down the steps around me, pulling at my instincts to steady her each time she neared an edge. She made a temporary home out of my shoe. Meanwhile Ben was trying to tell us that last week he’d seen fires burn more than half of the Stirling Range, a once pristine national park in Western Australia home to more than 1500 species of flora. What a mess.

In Australia, fires are the landscape, and have been for thousands of years. And while we’ve had disasters in the past...never before has this natural process transmogrified into the needy Old Testament God it is today, demanding acre after acre and life after life not just once or twice in the summer, but for the entire goddamned season.

I’d never been to the Stirling Range, or to most of the forests and bush lands where fires were burning. The Range is a four-hour drive south. Rural. Loved for its mountains and wildflowers. But as in the valleys of the Darling Downs in Queensland, and Gospers Mountain in New South Wales, and the shores of Mallacoota in Victoria, and Canberra’s hills in the Capital, and Kangaroo Island in South Australia, and so on, and so on, the now charred earth of the place, the acres of burnt trees left standing like grim toothpicks, the ceaseless flames and frayed nicotine skies had all reached me online, day after day, since September.

In 1939, long before the revolving firescapes of our contemporary moment, H.G. Wells visited Australia and saw firsthand a fire in Canberra. He shared his account in a local paper:

The bush fire is not an orderly invader, but a guerilla warrior. It advances by rushes, by little venomous tongues of fire in the grass. It spreads by sparks from burning leaves and bark. Its front is miles deep. It is here, it is there, like a swarm of venomous wasps.

But he’s wrong. Fires are not guerillas divorced from the landscape. In Australia, fires are the landscape, and have been for thousands of years. And while we’ve had disasters in the past—Ash Wednesday in 1983, Black Saturday in 2009, to name just two—never before has this natural process transmogrified into the needy Old Testament God it is today, demanding acre after acre and life after life not just once or twice in the summer, but for the entire goddamned season. How are we supposed to lounge on the beach when even the beach is burning?

Ben blamed this “climate emergency” on conservative Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who is famously pro coal (he once lifted a piece of coal in the air while speaking in the House of Representatives and, in the words of Australian novelist Richard Flanagan, “waved [it] around like it was the sacred Host”). The crowd cheered. Perhaps Ben was right. Morrison’s appetite for coal is not helping the world’s carbon detox. But the Prime Minister is a small man in a history of small men.

The next speaker, Dr. Sean Winter, a volunteer firefighter, began by acknowledging that we were meeting on the land of the Whadjuk Noongar people. “And perhaps,” he said earnestly, “if we’d continued with the ways of First Nations we wouldn’t”—a howl in the beer garden drowned his words and I finished his sentence—“be trying to fix this shit.”

Dr. Winter was brilliantly frank. The volunteer firefighting model, he said, was broken. With low humidity, high heat, and high winds the new norm, fires were burning bigger and with less time in between. He and the 100,000 firefighters shielding the country couldn’t keep up. The reason? Summer, his name’s rival, was on meth. “The season is getting longer and our window for [controlled] burning is getting shorter. And we’re only one degree of warming,” he said. “This is just the start. It’s going to get worse.”

"We need to love the air that we breathe, we need to love sacred things for things to change.”

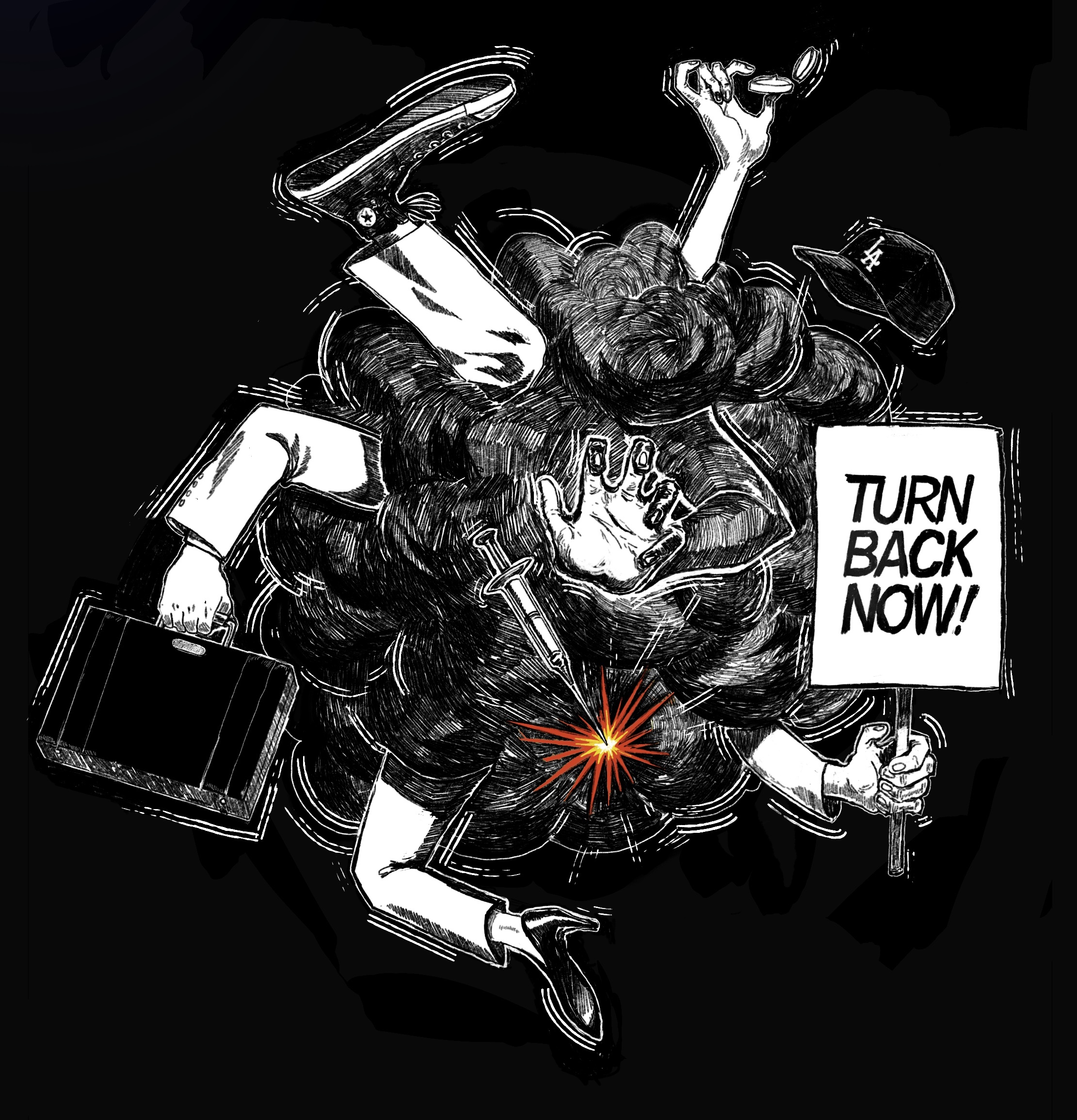

15 minutes had passed. The workday was officially done for. More people in suits and blouses began perusing the vigil like shadows. The host called for the next speaker and when he didn’t show, one of the Noongar elders seated nearby seized the microphone, forewent an introduction. She was passionate. The last of the day’s light slid over the library as she spoke.

“Once we start acknowledging the true history of this country,” she said, forthright with care, “we will heal together as one. We as Aboriginal people, we come from this Mother Earth—we is that plant, we is that gum tree, we is that koala. We must commit to this boodja, this land our country.”

Noongar man Daniel Garlett, deemed missing moments ago, had been found. Now he called on governments to rekindle Aboriginal land management practices extinguished by colonization—like low-level mosaic burning through heavy understory. Victor Steffensen takes this up in Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia. “The country is suffering,” he writes, “because no one knows how to look after the fire anymore.” But Garlett’s ancestral knowledge had been nothing but wind in white ears. And like the impassioned elder who spoke before him, he pleaded for unity and love. What else could he do for a mostly white audience?

“Find it in your hearts to love life,” he said, “and not only your children or the next generation that are coming up with them. We need to love the air that we breathe, we need to love sacred things for things to change.”

Everyone nodded in a way that felt cold and religious. We sighed in relief, a collective groan. Got those last important claps out in the open. And then it was time for five minutes of silence, after which Daniel Garlett would play the didgeridoo and lead us in a silent walk down James Street.

For five long minutes I had a kind of emotional stage fright. No matter how much I willed myself to mourn, to feel, to matriculate some kind of violent sorrow, I couldn’t. Sitting there on the yellow steps of the Cultural Centre, a mourner in a band of mourners, staged before the world and its myriad lenses, I felt completely denuded of my capacity to feel. Of course, it was only the wildest kind of grief that had led me there. Earlier in the week, my partner and I had wanted to show our care. In a community. With others. The event had promised an avenue. And for most of the vigil I had felt engaged in a strange kind of care, my concerns for the country fanned by the restless urgency of the speakers. But left to watch the city dress up in night, hear its grunts, breathe in the smoldering leaves and beer and heat, I felt hollow. I began to long for the sound of the didgeridoo to cut us away from the silence. Break open this show. Send us out into the night in pieces. When it filled the air I rejoiced.