America. What splendor! What poverty! What humanity! What inhumanity! What mutual goodwill! What individual isolation! What loyalty to the ideal! What hypocrisy! What a triumph of conscience! What perversity!

—Miłosz’s ABCs

“THE NATURE OF THE CALIFORNIA COAST,” wrote Czesław Miłosz, the Lithuanian-born Polish-American poet, essayist, and novelist, “...is somewhat demoniac. In its immensity, in its landscapes of parched, cracked soil, of forests whose trees remind one of granite columns, there is something which seems to mock at and to annihilate our fragile humanity.” It’s a vivid observation, one in which our sensitivity becomes a liability. Miłosz, an exile of profound proportions, believed the American psyche was formed of an obsessive-compulsive reaction to the nature of the continent. By the time the pioneers reached California, the perceived liberties and mysteries of the vast wilderness had transformed their wonder into conquest, their fear into greed.

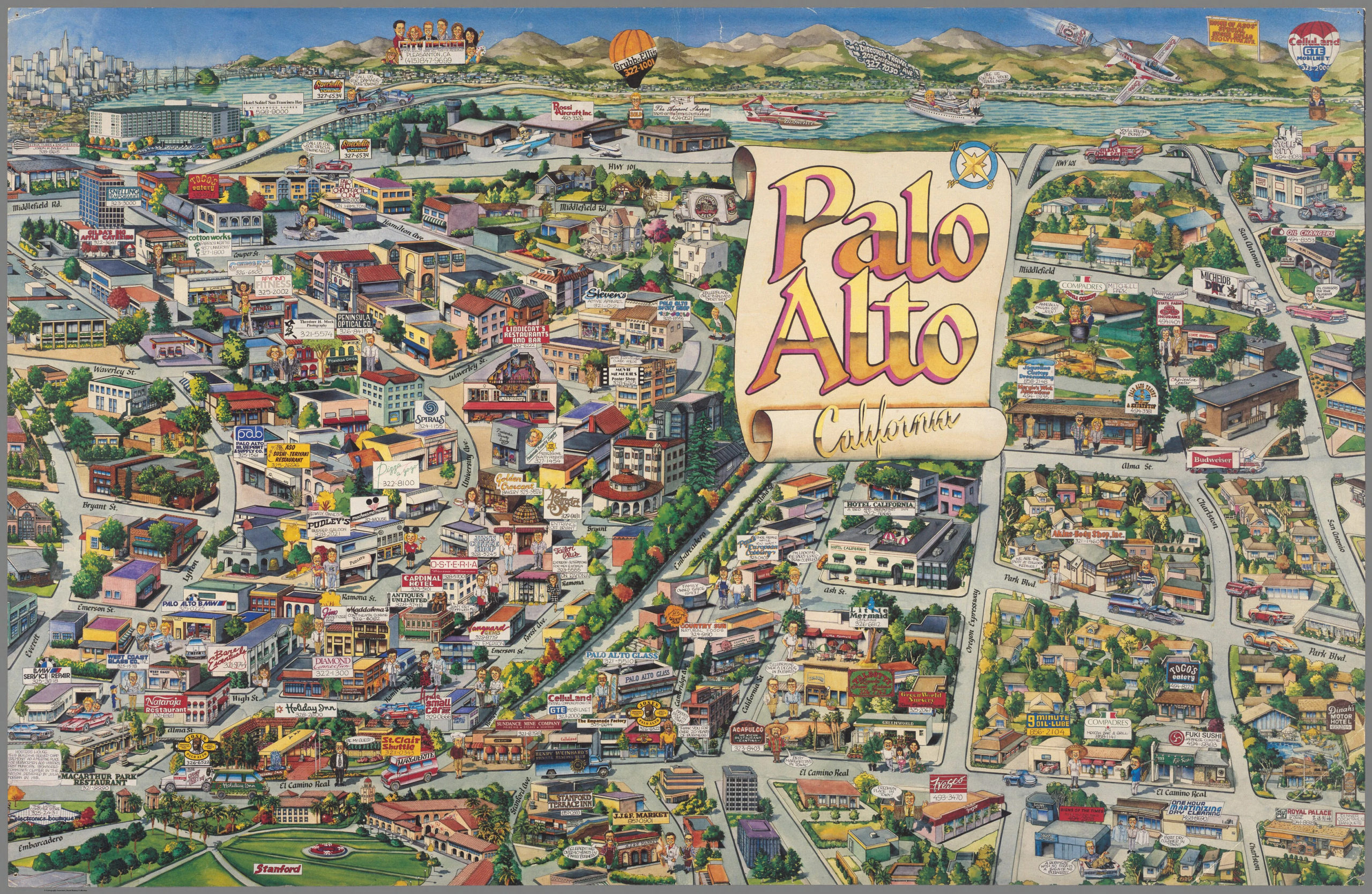

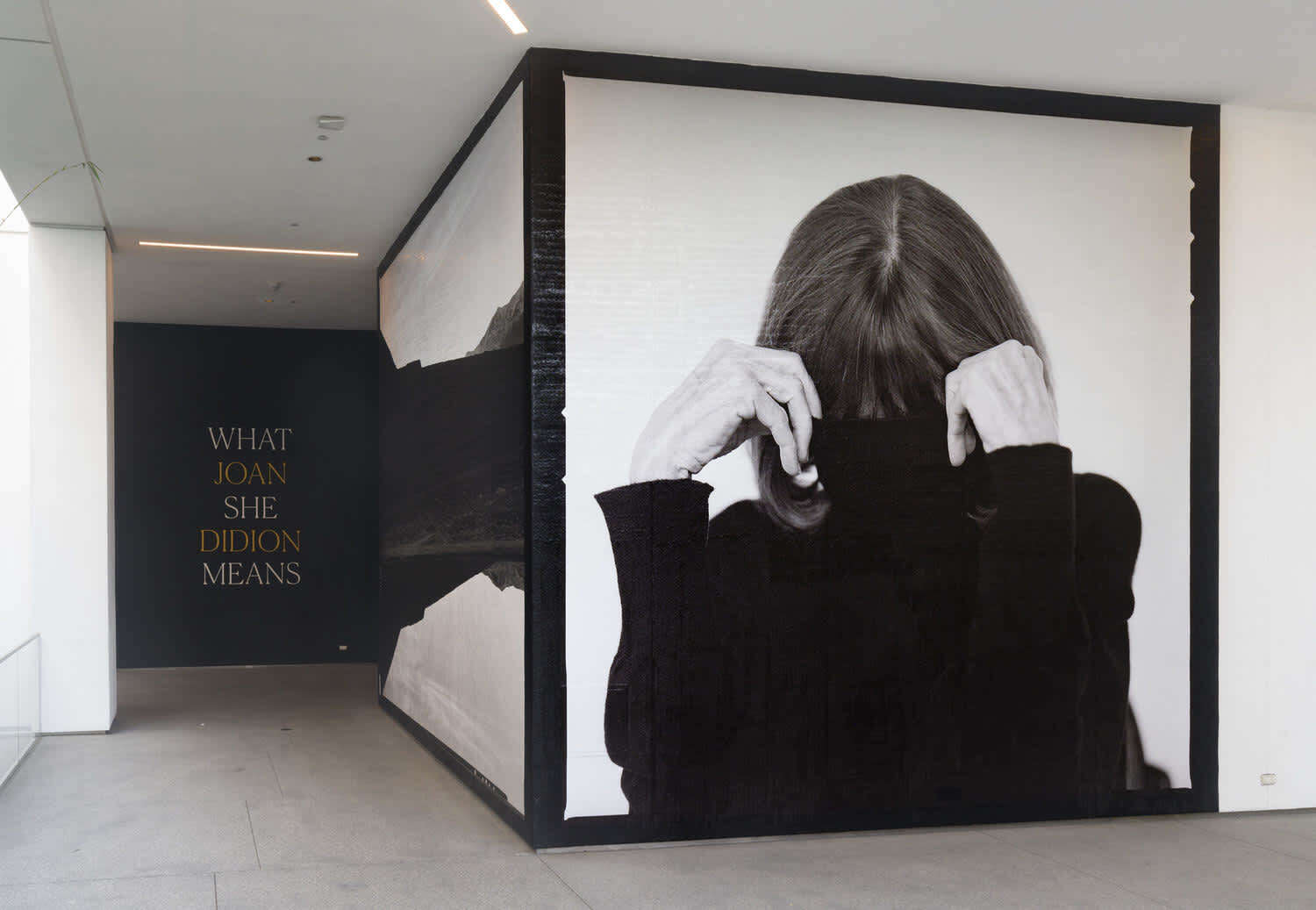

Czesław Miłosz, the 1980 Nobel Laureate, moved to California in 1960. “I came here to endure, but not to like it,” he recalled almost 30 years later. Invited for what he figured was a temporary academic post at UC Berkeley, Miłosz could have only been certain of one thing: He couldn’t go home—behind the Iron Curtain—again. In Cynthia Haven’s latest book, Czesław Miłosz: A California Life, the Polish master’s fertile yet uneasy Berkeley period is surveyed as one man’s battle to translate struggle into wisdom, despair into perseverance. From a modest cottage at 978 Grizzly Peak Boulevard overlooking the San Francisco Bay, Miłosz would produce some of the greatest works of his storied career, helping to give expression to the tumult of pain and beauty that characterized the most explosive century in human history. For, as Seamus Heaney stated, Miłosz had a gift “for going straight to the heart of a question… He is among those members of humankind who have had the ambiguous privilege of knowing and standing far more reality than the rest of us.”

Czesław Miłosz was born in what is now Lithuania on June 30, 1911, in the village of Šeteniai (Szetejnie). His father, Alexander Miłosz, was a Polish civil engineer whose ancestral line can be traced as far back as 1580. (Oscar Miłosz, the celebrated Lithuanian poet, was a distant cousin.) His mother Weronika, née Kunat, may, as legend tells it, have descended from a “Lithuanian chieftain whose tribe was eradicated during the Middle Ages by the Poles and the Teutonic Knights.” The Lithuanians, the last of Europe’s pagan cultures to be subdued by Christian savagery, were, according to Miłosz, the “Indians of Europe,” and their customs and plight remained buried deep within him. His childhood in rural Šeteniai lacked any of the trappings of the upper class, despite his ostensibly noble heritage. He romped among grassy rolling fields and dark woods, internalizing the natural order that would anchor his worldview.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914, however, ruptured this bucolic bliss. His father was conscripted to the Russian army and, as the war progressed, the family was drawn further eastward. As he tells it in his 1959 autobiography, Native Realm:

Talk about hunger never ceased. One could get bread that contained more sawdust than flour, saccharin and potatoes, but no sugar or meat. At night I would be awakened by battering at the door, stamping of feet and loud voices. Men in leather jackets and high boots would come in and, by the light of a smoking kerosene lamp, dump the contents of cupboards and drawers onto the floor… The terror-stricken faces of the women, my brother’s screams from his cradle, the whole miserable family sanctuary, or rather den, turned topsy-turvy—all this was not healthy for the heart of a child.

Following his father’s involvement in a failed attempt to incorporate independent Lithuania into the Second Polish Republic, the Miłoszs were exiled to Vilnius (Wilno)—then part of Poland. He remained there until the summer of 1937, when at 26, he moved to Warsaw. Again, from Native Realm:

When I reached adolescence, I carried inside me a museum of mobile and grimacing images: blood-smeared Seryozha, a sailor with a dagger, commissars in leather jackets, Lena, a German sergeant directing an orchestra, Lithuanian riflemen from paramilitary units, and these were mingled with a throng of peasants—smugglers and hunters, Mary Pickford, Alaskan fur trappers and my drawing instructor. Modern civilization, it is said, creates uniform boredom and destroys individuality. If so, then this is one sickness I had been spared.

Miłosz was in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded in September 1939. Along with colleagues from his post at Polish Radio, he escaped to Lviv (Lwów) without his wife, Janina. They were reunited when he returned in the summer of 1940 (and remained mostly together until her death in 1986). He participated in the underground. He aided the city’s Jews. He prepared an anthology of wartime poetry. Hypnotized by The Waste Land while bombs illuminated the night sky and the city around him was methodically razed, he translated T.S. Eliot’s Collected Poems, 1909-1935. “My generation was lost. Cities too. And nations,” he wrote in his poem, “Diary of a Naturalist.” In “Tiger,” his essay on Polish writer Bolesław Miciński, he expanded: “I was not born into a class that knew how to prize [money] and I had walked out of too many burning cities (literally and metaphorically) without looking back… Soft carpets, gadgets, neat little houses I associated with flames and destruction.” Then in 1944, a mysterious stranger appeared. As Haven describes it:

Miłosz was caught by the Germans and put in a makeshift camp. A majesticnun appeared that evening, insisting he was her nephew. For an hour she spoke fluent German with his captors, and then led him away through the main gates. He had never seen her before, and he never saw her after that day. He never knew her name.

Just after the war, Miłosz moved first to New York City and then to Washington D.C. as cultural attaché for the freshly formed People’s Republic of Poland. Ostensibly responsible for Polish cultural occasions such as concerts, art exhibitions, and literary and cinematic events, he began writing a series of essays on American writers for Polish readers. “What really preoccupied me,” he admits in “Tiger,” “were studies on Eliot and Auden, anthologies of American poetry, the world of Faulkner and Henry Miller, the poetry of Robert Lowell and Karl Shapiro, periodicals such as Partisan Review or Dwight Macdonald’s Politics, and exhibits of modern art.” His first American period set the stage for the polarities of American art and American culture to percolate within him, bouncing off his own tensions between hunger and guilt, sin and redemption.

In 1949, Miłosz returned to Poland for the first time in four years. He was appalled by what he witnessed. His experiences formed the basis of his landmark book, The Captive Mind (1953), a vivid look at how totalitarian regimes poison the intellectual and cultural well of nations, told through four profiles of promising writers he had known who conformed to Stalinist doublethink. “Peasants go mad with despair,” Miłosz wrote to a fellow exile, “and in the intellectual world state control is deeply entrenched and it is necessary to be a 100% Stalinist, or not at all.”

His first American period set the stage for the polarities of American art and American culture to percolate within him, bouncing off his own tensions between hunger and guilt, sin and redemption.

In 1950, Miłosz was summoned back to Warsaw. Soon fearing for his own safety, (“He is deeply detached from us,” Polish Writers’ Union General Secretary Jerzy Putrament wrote to his superiors in July 1950), Miłosz fled to Paris, aided by staff at Polish émigré publication, Kultura. On February 1, 1951, he formally defected. His French years, though isolating—he lived in poverty while his wife and young child remained in the U.S.—were productive. In addition to The Captive Mind, he published two poetry collections, two novels—in 1955 alone—and many more essays and reflections. His numerous appeals for American visas were denied during the McCarthy years; in America The Captive Mind had the ironic effect of painting him as a Soviet spy, or at the very least a Stalinist apologist.

In the spring of 1959, however, with the Red Scare finally over and his reputation enhanced by the decade’s work, Czesław Miłosz was offered a position as visiting lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley. Enchanted by his “Romantic vision of America” as natura, the term he used for the comparatively stable natural world running alongside the frenzy of human affairs, he imagined for a moment his post would bring him tranquility and room for contemplation. But, as Haven puts it, “Berkeley was about to become a lightning rod for devenir, the world of change and becoming, and he would be in the thick of it.”

“Being high on a mountain,” Miłosz’s former student Mark Klus observed, “gave him a certain viewpoint that fostered an apocalyptic outlook.” Miłosz desired and needed an atmosphere conducive to observation and contemplation. From his crow’s nest in Berkeley, exile among exiles, he witnessed the growing pains of a culture barrelling toward another major turning point in modern history. The Baby Boomers, improvident children of victory over the Axis of evil and the ensuing years of unprecedented prosperity, were coming of age in an electric and eclectic way. But periods of great unrest often follow periods of great prosperity. Between 1964 and 1971, the Bay Area saw the Auto Row Protests, the Free Speech Movement, the Third World Liberation Front strikes, the “Battle for People’s Park,” and the Occupation of Alcatraz. “Berkeley in the [Sixties] was heady with the scent of night jasmine and tear gas,” publisher Steve Wasserman wrote, “[it] was rife with rebellion.”

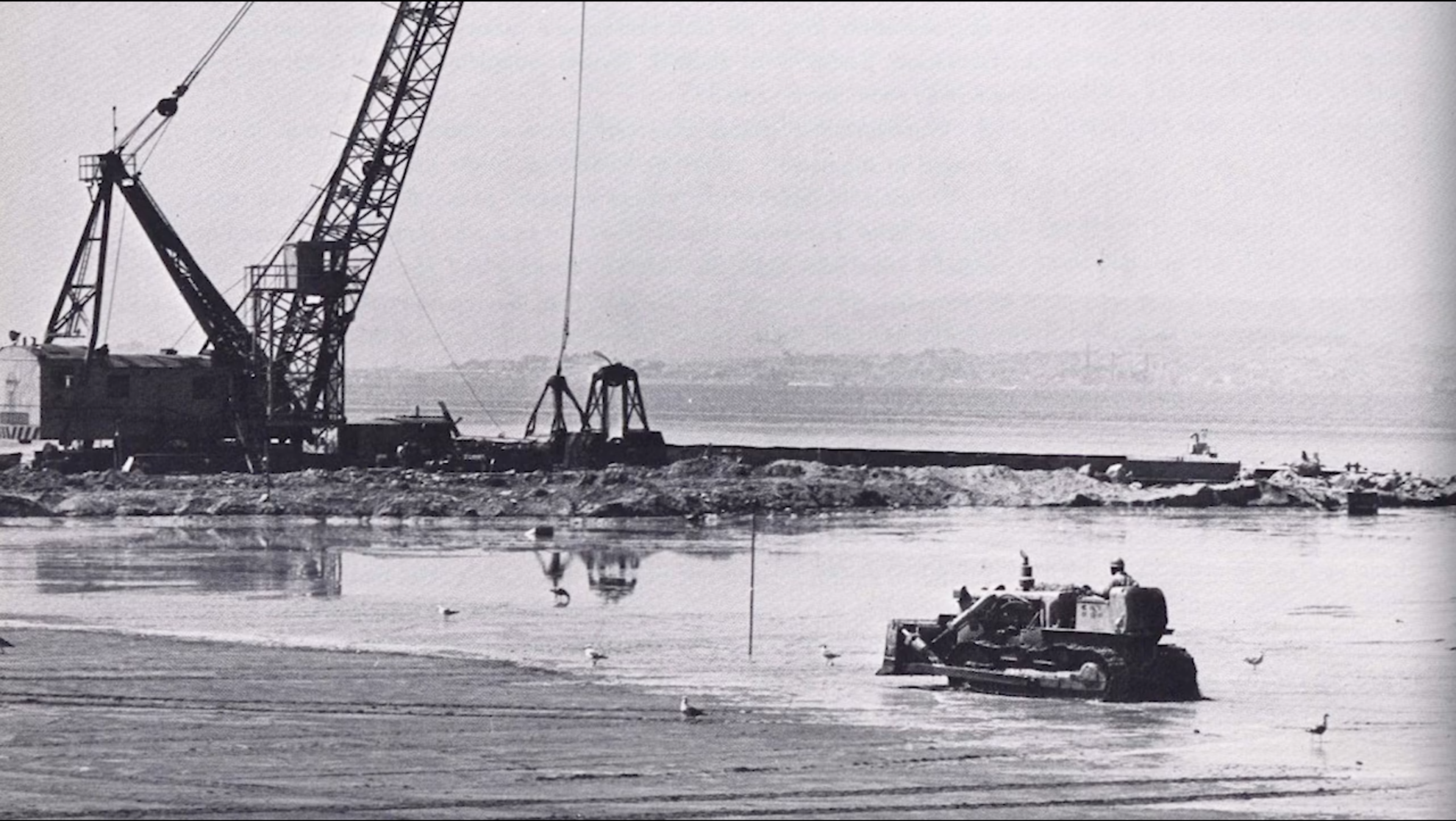

“I do not wish to play games with chains of causes and effects,” Miłosz wrote in “Facing An Expanse Too Large,” “and so will simply acknowledge that this continent possesses something like a spirit which malevolently undoes any attempt to subdue it.” His 1969 collection, Visions from San Francisco Bay, is the closest Miłosz would come to a blow-by-blow document of a nation in flux from the point of view of the last stop in America, the San Francisco Bay, that mesmerizing bookend to the deceptive embrace of New York Harbor. A vivid batch of essays, Visions contemplates the labyrinth of mirrors guiding the troubled rise of modern, rational man.

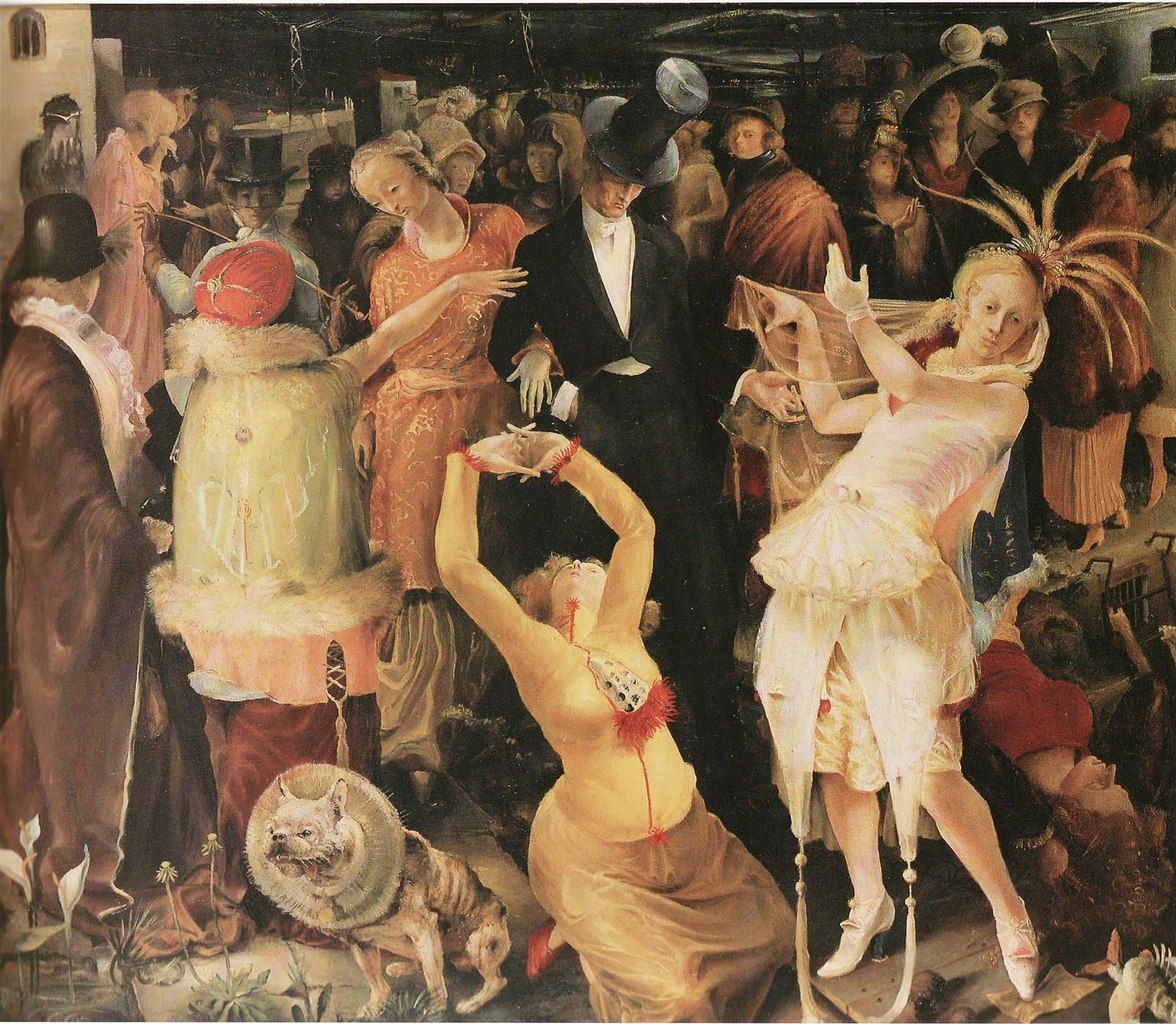

Miłosz struggled to articulate a humanistic interpretation of American society. In “The Agony of the West,” he tried to uncover why eras of great technological progress seemed ever-accompanied by cries of “decadence and rotting” from its artists and thinkers. “The myth of decline and decay has to be contagious. I say myth because there is obviously a certain unity of aura and tone stronger than truth or untruth at work here.” From where exactly had the West fallen? Which ideal state of equilibrium and vigor? Nowhere anyone can agree on; anyplace, anytime it seemed, but now. And the “now” of this provocative—and proactively opaque—myth goes back centuries. The deeper into the collection, the thornier, and perhaps more irreconcilable the assessment of his subject matter becomes. “My theme,” he writes in “The Evangelical Emissary,” “which I have been approaching indirectly, is the erosion of the system of ideas and customs which form the American way of life.”

America’s founders, fattened on the Enlightenment, viewed progress as an idea wedded as much to a moral awakening as it was to a scientific subjugation of nature and its resources. California, the terminus of Manifest Destiny, epitomized a maddened reinvention in response to a reinvention. It elaborated on a radical obsession to wipe the slate clear, to start from virgin land for this fresh nation of new men, “the brazen arrogance of the ego not ashamed to proclaim it cared only for itself,” as Miłosz called it in “The Events in California.”

For Miłosz, historical consciousness was indispensable to nations and cultures, something that augmented people as they moved forward through time. “The awareness of one’s origins,” he wrote in Native Realm, “is like an anchor line plunged into the deep, keeping one within a certain range. Without it, historical intuition is virtually impossible.” Absent this regard among the “forward thinkers” for whom barbaric allowances are still “regrettable but inevitable” aspects of progress, is it any surprise then that America’s amnestic approach toward its origins—its sense of self largely a children’s book amalgamation of myths and legends primed for adults with increasingly childlike aspirations—would form a distressingly arrogant and merciless exceptionalism? Perhaps Big Tech’s greatest feat is the swiftness with which these “Enlightened” men came to remake the world in an image of their own choosing with absolutely no interest or regard for contrasting, independent or autonomous worldviews. Writing in “Tiger,” Miłosz believed that Americans

accepted their society as if it had arisen from the very order of nature; so saturated with it were they that they tended to pity the rest of humanity for having strayed from the norm… They did not realize that the opposite disablement affected them: Loss of the sense of history, and, therefore, of a sense of the tragic, which is only born of historical experience.

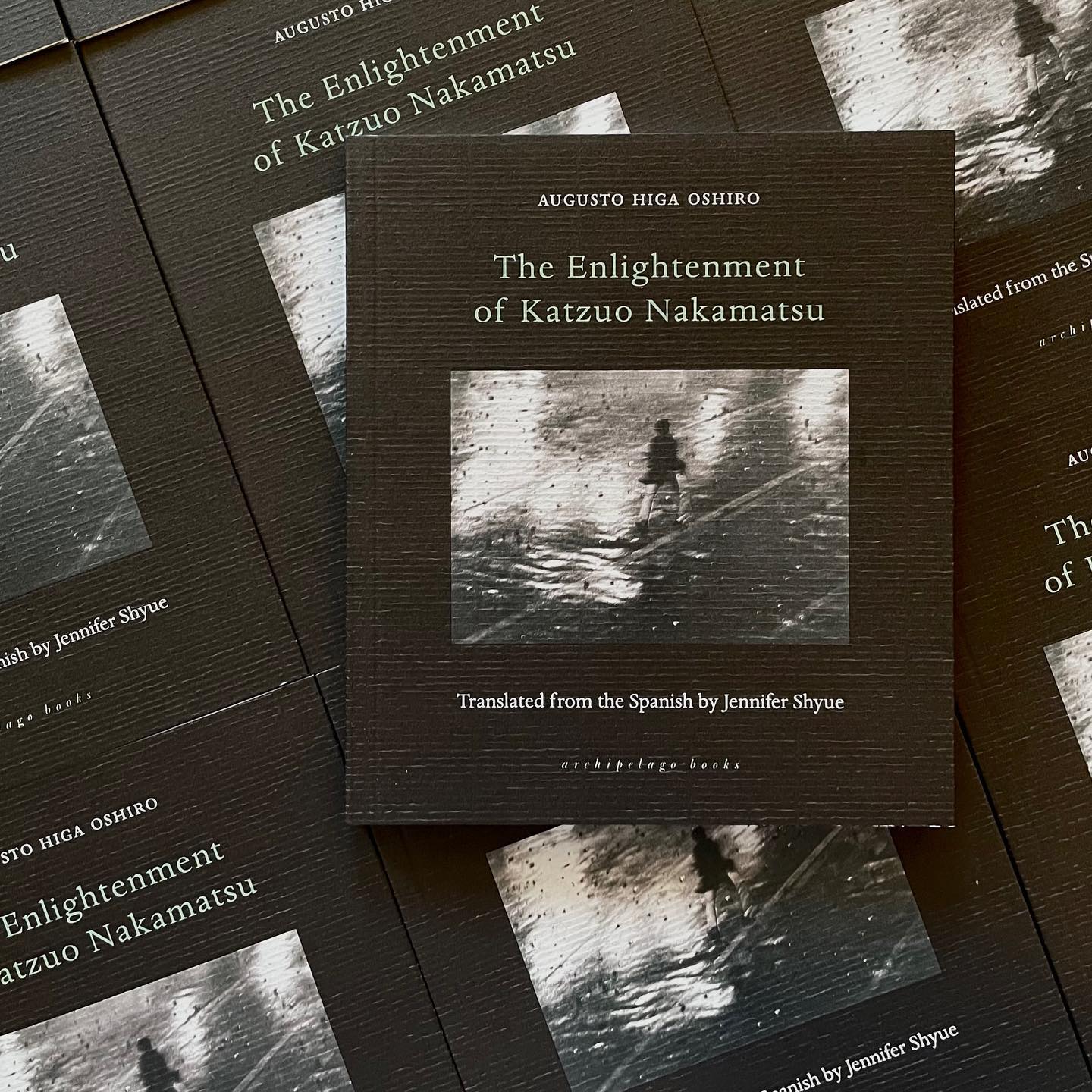

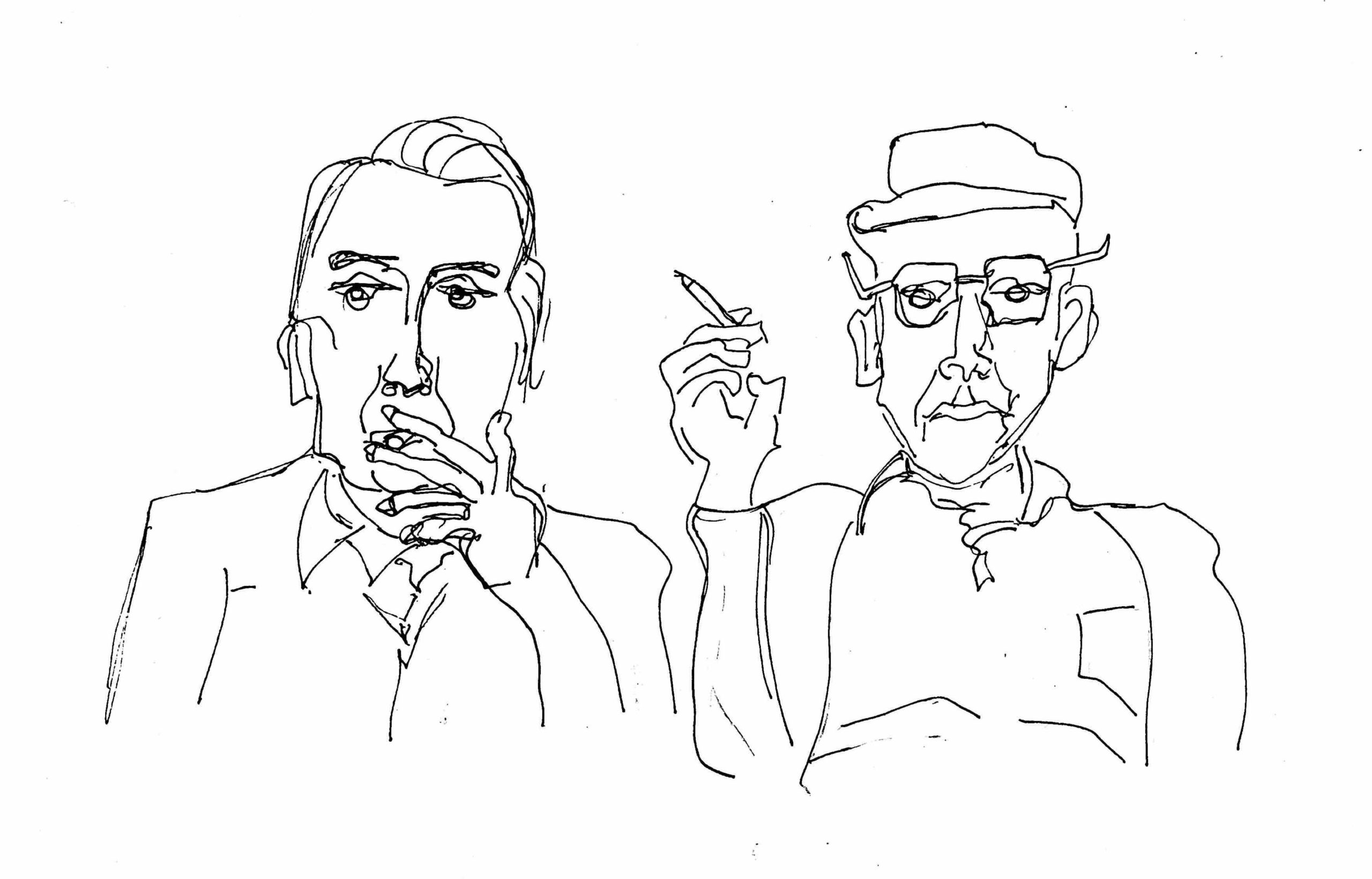

In 1945, Miłosz released Ocalenie to an annihilated city. Containing some of his most startling and vivid poems, Ocalenie—as a book and a word—signified salvation or deliverance. It was exactly what Poles needed at the time. In 1973, Miłosz, alongside Peter Dale Scott, began translating work for his Selected Poems. Scott had “never before met such critical acuity combined with such passionate erudition and love of words.” Yet, much to Scott’s bewilderment, Miłosz opted to significantly alter the tone of a number of pieces from his seminal collection.

There are many takes on the art of translation. The nature of language essentially guarantees some irrevocable loss in meaning or felicity of phrasing between tongues; call it the conversion fee, like the one you encounter at a currency exchange. Despite Scott’s reservations, Miłosz insisted on rendering “Ocalenie” as “Rescue” in the published book. He changed “Przedmowa” (which means “Forward” or “Preface”) to “Dedication,” and, despite its famous tone-establishing beginning and ending, he moved it from the beginning to the middle, thus altering the original theme.

According to Haven, Miłosz was “gradually turning away from the vatic tradition [of poetry], remembering the effect it had on an idealistic generation of young men who gave their lives in a gesture of futile resistance and were buried in the wreckage of Warsaw.” He set his sights on adapting his work for an American audience whose traditions and expectations for poetry were different. These were the days of Vietnam after all. One could interpret the prevailing mood among many young Americans (certainly the ones at Berkeley) to be unreceptive to Western traditions of morality and faith when young men had good reason to fear their own birthdays and gruesome images from the conflict in Southeast Asia dominated the airwaves, rightful grievances the youth blamed on what Miłosz dubbed “mental inertia of the older generation.”

Miłosz, sometime leftist and always independent thinker notwithstanding, was born and raised in a deeply religious culture. He remained a faithful Catholic his entire life. In Poland, “the Catholic paradigm that has endured for two millennia informs every level of society. It sees the family, not the individual, as the building block of community.” In America, his status as exile was reinforced by his feelings of isolation amid the near ubiquity of Protestant concepts. It is impossible to imagine Czesław Miłosz—intimidating eyebrows, mien, and all—making deliberate changes to his poems in response to the popular mood. It is worthwhile, however, looking at the connotations of these words as they passed from one tongue to another.

Words give form to our urges. Likewise they color, for better and worse, the tenor of our time.

“Salvation” may have been too overt an invocation of spiritual concepts, sure. As Haven points out, Western society was continuing a long-running turn away from art and religion to science and technology to answer age-old questions. But “rescue” as an act and a promise may have revealed an innate understanding of the American psyche. As it was then (and to an extent exists today), entrenched Lefties determined to rescue Americans from the hang-ups that held their society back engaged in a tug-of-war with Nixon’s conservative contingent working hard to rescue the citizenry from lawlessness and cultural dissolution. (On a purely pop-cultural note, in 1972 going on ’73, the youth culture could be quick to associate “Deliverance” with John Boorman’s 1972 box-office smash of the same name starring Burt Reynolds and John Voight in which city slickers are given a horrifying awakening during their attempt to convene with nature, exposing a grim portrait of mankind never quite before depicted on mainstream screens.) By altering a word here and there, Miłosz channeled urgencies and tendencies that were floating around in the American zeitgeist. Words give form to our urges. Likewise they color, for better and worse, the tenor of our time.

Surrounded by student protestors, counter-culturalists, and Black Panthers, Miłosz’s work had to grow and morph in California as Berkeley began to rage and burn. “America” as a culture, still something of an awkward youth when compared even to Poland, burned with the flames of many explosive concepts—most of which were either juvenilely half-baked or overcooked in the lard of capitalist virtue. But the question remained: rescue or salvation? Perhaps what drew Miłosz to the works of America’s vatic poets—Whitman, Jeffers, Ginsberg (although he had reservations about each)—even as he was turning away from the “lofty hopes for poetry” he’d had in his youth, was some sense of divine madness and spiritual daring. Each channeled a truly radical approach to human wisdom while maintaining, to varying degrees, an orthodox approach to the calling. For Miłosz, the poet’s role was one of responsibility to beauty and sustenance: “What is poetry which does not save / Nations or people?”

But Miłosz acknowledged the near impossibility of his endeavor to bridge two dissociated entities: the rational and the divine. “He’s a poet, not a philosopher,” observed poet Robert Hass. “A lot of his ways of thinking about things are very instinctive.” As a witness, Miłosz was on a quest for some eternal truths, perhaps some authenticity of experience and transcendence. Perhaps our civilization, never having internalized a sense of place and a sense of esse despite amassing wealth far beyond the wildest dreams of the Spanish kings, clings to material objects and a restless acquisitiveness as a way to find purchase in an eternal state of flux.

These terms—“authentic,” “spiritual,” or “transcendent”—have become highly marketable today, hot commodities for developers and social media gurus alike in an attempt to fuel the ceaseless furnace of capitalism. The relentless emphasis on tomorrow, the brighter things that will be ours if we submit today so we may forget our yesterdays has been a battle cry in California for at least 150 years. Looking out at a nation of orphans, Miłosz saw that this civilization was prey to the malevolent forces of history which have been at work at least since the days of Canaan. Forebodingly, in “Emigration to America: A Summing Up,” Miłosz, overlooking the endless Pacific flowing out from one of Moloch’s jewel cities, his antennae set to disturbances far in the future, wrote:

The last spiritual remnants of the epoch of the steam engine are already disintegrating and dying out; man has found himself before something still unnamed and though his consciousness lags behind general transformations, he does perceive that everything happening now to our entire species is enormous, ominous, and perhaps ultimate.

“Americans,” Haven writes, “often overlook how much their cultural and historical sensibility has been shaped around a radical Protestantism, with an emphasis on individualism, hard work, and private revelation… Americans are always seeking quirky and idiosyncratic means of personal ‘salvation’ and enlightenment…” Alongside the gambit for the moon, the microwave foods, the Ford Mustangs, faith and redemption in the face of growth and acquisition helped make this nation—in the words of H. L. Mencken—“incomparably the greatest show on earth.” Miłosz, back in the 1960s and 70s, must have noted the many curious, swirling influences on the Californian mind—the spiritual quacks and gurus and Technicolored oddballs promising a top-down revamp. He had, according to Haven, “entered a world whose ethos was formed by this turbulent sensibility, contributing to an anomic society trapped in restless Gatsby-like self-reinvention, self-expression, paleo diets, and earth-worship, in the undying quest to make a more perfect ‘me.’” Where, in all this stuff, did poetry fit?

While exploring Miłosz’s resistance to duplicating the role of the wieszcz, the vatic poet of Polish tradition, in America, Haven asks,

What did it mean to water the ashes of the dead in a country that defied death with its ubiquitous youth culture, its consumerism, its television commercials and plastic surgery, the desolating emptiness of its deserts stretching to the horizon? What did a stance of ‘resistance’ mean? A resistance to what?

Miłosz was consciously leaping into a new, hybrid state of being and expressing—that of the exile. Constantly feeling, translating, resisting, communicating, while the terms around him chafed against their meanings as quickly as he appraised them. At a certain point, as Haven observes, “he lets go.”

But never his responsibility. Haven recounts an episode when a fire broke out on the Berkeley campus in 1969. “What makes them rage is that they have too much,” he famously growled. While on the surface his disapproval carried with it the conservative establishment, he empathized with the student’s frustrations, if not their methods. Miłosz wrote of the incident:

The strength of the collective emotion was not in proportion to the causes of their dissatisfaction, [which were] trivial if viewed rationally… [This] was a vicarious discharge: The university authorities were treated as representatives of authority in general. The students… were united by the tacit, and for them, obvious premise that any authority issuing from an evil system and protecting that system was itself pure evil.

Insofar as academics could be considered representatives of “evil systems,” Miłosz’s first-hand experience with the regimes of both Hitler and Stalin forced him to consider just how it is people are supposed to differentiate the truly evil acts from the quotidian and mundane moments of human weakness, a consideration the youth simply could not yet fathom.

The young Americans wanted change “now!” The “authorities” cowered. Even while “suspect, his reasoning often elusive and politically ambiguous, and grounded in experiences a world away,” Miłosz noted:

These young people were inspired by the best intentions… Nevertheless I was one of the few professors who dared to vote in the university senate against some of the absurd proposals presented—for example, a proposal to abolish the study of foreign languages. Most of the faculty behaved in an incredibly cowardly and conformist fashion.

Flawed instructors balancing the devil of responsibility and authority on one shoulder with the devil of mortgage payments and social status on the other. There’s “pure evil.” Still, those concessions never went the mile.

Stifled in their quest to remake their world, the student revolutionaries eventually tired out and cashed in, from Wall Street to Hollywood to Silicon Valley, reared as they were on a system that was never fundamentally up for debate. Their dabbling in radical politics had been little more than a rite of passage, something many middle-class liberals considered as integral—and as disposable—as baby teeth. And the conformism many of them later engaged in—the yearning to own property in a fashionable middle class burg, to hold court in fine, wood-paneled restaurants in Allen Ginsberg’s cities of Moloch, their peers' eyes glowing with wonder, glee, or envy—was merely a more urbane and liberal brand of “the American dream.” Intimate with the suffering that superseded the hopes of party ideology, Miłosz’s belief in the role of poetry as a way through, toward a path of goodness, was intrinsic to his hopes for human progress.

“America was a land where everything was too big, too moneyed, too lavish,” he complained during fits of occasional exile malaise, “and populated by self-centered people who were too focused on their own consumerist comfort to care about anything besides themselves.” As the decades wore on and new fits of political protest were stymied by newer, flashier, more encompassing products and louder, more charismatic—and duplicitous—heads of state, Miłosz’s work withdrew more and more into the realm of the spiritual and the arcane. “Once again everything becomes embroiled and unclear,” he wrote in Striving Towards Being, his collected correspondence from the 1960s with the theologian Thomas Merton. In “Facing Too Large An Expanse” he expanded, “now I seek shelter in these pages, but my humanistic zeal has been weakened by the mountains and the ocean, by those many moments when I have gazed upon boundless immensities with a feeling akin to nausea, the wind ravaging my little homestead of hopes and intentions.”

Early in October of 1980, Czesław Miłosz’s quiet, contemplative life atop Grizzly Peak was upended when he won the Nobel Prize. In his acceptance lecture, he addressed the poetic necessities and desires of engagement with être (or contemplating and capturing things as they are) and the more pressing, societal requests of devenir (or participating in ushering in what’s to come). Throughout his life he’d been faced with the choice between artistic vision and solidarity with one’s fellow man in resistance. His conclusion? “All art proves to be nothing compared with action… To embrace reality in such a manner that it is preserved in all its old tangle of good and evil, of despair and hope, is possible only thanks to a distance, only by soaring above it—but this in turn seems then a moral treason.”

Miłosz’s concern and deep interest in environmental issues, the woes of consumerism, the rights of indigenous peoples, and even trauma theory (“It is possible that there is no other memory than the memory of wounds”) was deeply prescient. Additionally, his first-hand experience of illiberal regimes and their effects on once-liberal societies all make for a collection of subjects that are none other than the major subjects beleaguering overstimulated contemporary minds. Faced with the uncertain future of democratic societies, The Captive Mind captures with startling potency the question of motive: Was it fear, opportunism, or something altogether different that drove conformists and collaborators?

In his review of The Captive Mind, Irving Howe wrote: “There was also embedded in the totalitarian idea some darkly magnetic force, some delusion of a false collective to which intellectuals were at least as susceptible as proletarians, students, and peasants.” The desire to belong is not only a vital element of being human, but the intrinsic element manipulated by totalitarianism. What’s curious about today’s mythic struggle for this nation’s soul is the conviction that what stands to be saved is liberty itself, while the only way to achieve this is to conform to increasingly crippling and absolutist ideologies spurred by paranoia. Whatever cheap myth Americans were hawked in school for the last century or so has run out. Now, in the adulthood of this nation, a vicious family drama plays out between those committed to protecting a diluted—borderline delusional—vainglorious history and those who will stop at nothing until every closet door is opened and every last skeleton dumped on the living room floor. But to what end? And what role is the drama expected to play in stymying the reckless, willfully ignorant, growth-obsessed ruling class?

It is up to us to be active participants, and to learn not to rely on or cede increasing chunks of our humanity to those for whom our humanity is but a commodity. Power lies in the exploitation of faith and trust. History can neither be bested nor undone, it merely is.

While Miłosz did not live to greet the full maturation of neoliberalism’s love child with Big Tech, I don’t believe he needed to witness the proliferation of entrepreneurism as the new human apex, or the deterioration of the imagination in a society completely taken in by capitalist realism, to have intuited that totalitarianism could return, albeit in a more complex and evolved form congenial to the tenets of a digital world. Too many of his poems read like tender warnings. But is guilt the American inheritance?

As a witness to the 20th century, Miłosz’s writing leaves the burden of work on us, on how we are to interpret his interpretations. According to his close friend Aleksander Fiut, the most important thing in Miłosz’s life was redemption. So how will mankind redeem itself? “All of us yearn naively for a certain point on the earth where the highest wisdom accessible to humanity at a given moment dwells,” Miłosz wrote in “Tiger,” “and it is hard to admit that such a point does not exist, that we have to rely only upon ourselves.” What one finds boiling under Miłosz’s reserve is a radical engagement with notions of truth, despair, and revelation. Life is both a causal chain and a calculus at heaven. Personal agency is crucial if a secular, liberal society is to function.

“The science of life depends on the gradual discovery of fundamental truths,” Miłosz wrote in Visions from San Francisco Bay. The impetus is on us, not merely to unleash the self-actualized capitalist brand dying to climb out and make a fortune, but to make this world—and our role in it—a reflection of what we truly value most. It is up to us to be active participants, and to learn not to rely on or cede increasing chunks of our humanity to those for whom our humanity is but a commodity. Power lies in the exploitation of faith and trust. History can neither be bested nor undone, it merely is. Haven, exceptionally well-versed in Miłosz’s work, suggests his oeuvre consists of “an ancient quarrel with the cruelty of the universe and the inevitability of suffering,” one where the poems often end “with beauty, only stated as a challenge.” With Czesław Miłosz: A California Life, Haven succeeds in portraying a person grappling interminably with this challenge.

California is a young civilization, but it is no longer unprecedented, and as such no longer excusable. There is a grave vastness beyond the imported palm trees, the sweeping vistas, and the crashing mantra of the Pacific, a vastness of responsibility. History is like an ill-fitting suit, always present, always a reminder of how far you’ve come—or gone—from somewhere else. What can we learn from Miłosz? For Haven, this is it: “this art, a twinning of vision and historical consciousness. One sings of the future, and in its singing creates what it has sung; the other looks backward, soberly, keenly aware of how our finest intentions go awry, how closely evil bites our heels. Together, they mark the distance between being and becoming.”

Czesław Miłosz: A California Life

by Cynthia L. Haven

Heyday, 2021

$26.00